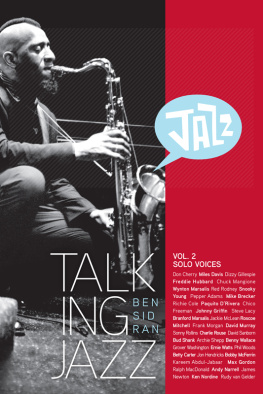

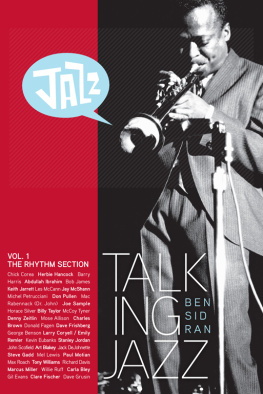

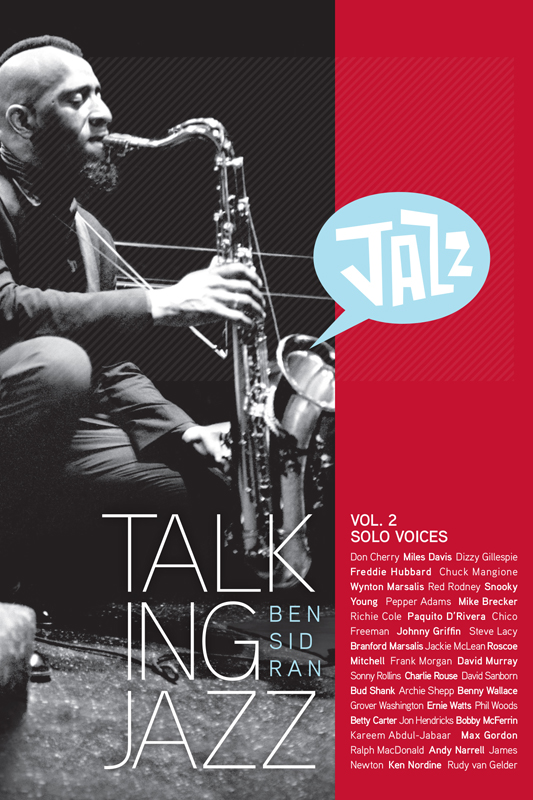

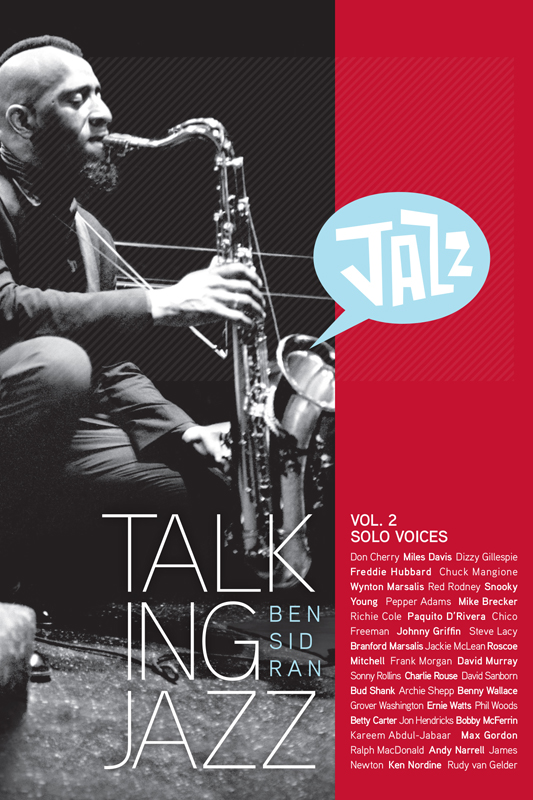

Talking Jazz with Ben Sidran / Vol. Two: Solo Voices

1992, 2006, 2014 Ben Sidran

ISBN: 9781450753678

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U. S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means or stored in a database or retrieval system without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Nardis Books, a division of Unlimited Media Ltd., Brooklyn, NY

Other Nardis ebooks by Ben Sidran:

Black Talk: How the Music of Black America Created a

Radical Alternative to the Values of Western Literary Tradition

Ben Sidran: A Life in the Music

There Was a Fire: Jews, Music and the American Dream

For a complete catalog of books, music, videos, lectures and links please visit

www.bensidran.com

INTRODUCTION TO THE 1st EDITION

The following talks took place between the summer of 1984 and the spring of 1990. Edited versions of these conversations aired on the National Public Radio series Sidran On Record, which ultimately amounted to more than one hundred interviews, interspersed with musical demonstrations and recorded examples. While the transcriptions in this book lack these aids, they were taken from original interview tapes, rather than the edited radio shows, and so in some instances are a more complete record of what was said than were the programs.

Of course, we lose a lot going from the living voice to the printed page. Imagine the voice of Miles Davis coming to you across a table on the patio of his Malibu beach-house, with waves breathing in the background. On the other hand, these interviews read as well as they played on the air, and you can really get a sense of the individual. In editing the text, Ive tried to keep as much of the spoken voice as possible, preserving things like syntax, rhythm and idiom. Youll find a fair number of ahs and umms which give you an idea of favorite thinking markers and describe the air in the room. Looking back at the many afternoons and evenings spent talking, an ardent fan was sitting there, whose main objective was to capture the human side of some great artists. In Phil Woods phrase, these are Americas warriors, or samurai, in the language of Abdullah Ibrahim.

As the subtitle says, this is essentially an oral history of a period in American music, as told by a cross-section of people who breathed life into it. And even though trying to capture an oral tradition in writing is like trying to capture the sea in a fish net, there is always the hope that these interviews, at minimum, show the kinds of things a musician has to deal with on a day to day basis, the things they like to talk about. There is also some illumination of the mechanics of making the music, of improvisation and other methods of the art. These interviews, then, can be read on many levels; as anecdotes, instruction, first person reportage, reports from the battle front.

Actually, these arent interviews so much as directed conversations. For the most part, we just hung out and talked about whatever came up, areas of mutual interest. The time spent, usually a few hours, passed very quickly. Of course, I did have favorite topics, and, from time to time, an agenda. I pursued questions like What is style? and How does one find it? or What is the impact of technology on jazz? and Whats the difference between captured music and manufactured music? I suppose these themes might provide a kind of backbone to the series. But, as so often happens in jazz, what you stumble on is better than what youre looking for. Because, for me, something fascinating is how often these folks revert back to a single generality to explain the heart of their work: the concept of sound.

Its one of those deceptively simple ideaswhat do things sound like?but it comes up so many times that one would be a fool to dismiss it as merely another limitation of the language, or the inability of one language (English) to describe another (Jazz). Whether it was Miles Davis talking, or Gil Evans or McCoy Tyner or Michel Petrucianni, or any number of other people, it was clear that the essence of their work is not in the choice of notes but in the sound of those notes. And, as corollary, the sound of those notes (their acoustic shape) is determined by the way in which they arrive. Style, then, is a function of music that arrives right on time and in absolutely the right way. There is a kind of definitiveness about jazz when its done right, as if it couldnt have happened any other way. Style is the expression of a personal imperative. Miles says, Its like your sweat.

But again, this was the subtext and rarely on our minds when we met, drank coffee, and passed the time in front of a microphone. In fact, one of the greatest pleasures of living the jazz life is just how down to earth it all is. If it doesnt play on the street, its left on the floor. The old saw still cuts: It dont mean a thing if it aint got that swing. Jazz is stuff you can use.

Ben Sidran / 1992

INTRODUCTION TO THE 2nd EDITION

Since the original publication of Talking Jazz, Ive had the chance to discuss its themes with many people; the two topics that come up most often are, Well, how is jazz doing these days? and, Whats jazz all about, anyway? Obviously, these are part of the same question, and therefore, the same answer applies:

In many ways, these are the best of times and the worst of times for jazz.

On the one hand, music schools are turning out thousands of thoroughly prepared young players who at an earlier age are better versed in the grammar and idioms of jazz than ever before. The recorded evidence speaks eloquently of the success of our education system. Again and again, a major record label touts another nineteen or twenty year old musician who is burning up their instrument, playing quotes from the old masters, and leapfrogging through the most difficult chord sequences with the greatest of ease. In the popular press and the trades alike, this is offered up as the promise of a bright jazz future.

On the other hand, most of the new jazz prodigies dont sound like anybody. That is, you cant identify their voice on their instrument of choice; you cant pick them out of a crowd. They are just musical faces in a landscape overpopulated with faces. Often dressed in expensive suits and beautifully backlit in photos, they offer up very little in the way of hope or salve for the human condition. In short, they are playing notes rather than feelings.

Why is this? How can one master every aspect of jazz technique and vocabulary but somehow fail to develop ones own voice? Indeed, why does the former sometimes preclude the latter?

Theres an old saying that addresses this question: It aint what you do, its the way how you do it. The way how you do it is style. And style is the substance of jazz; its what jazz is all about.

Perhaps the greatest mystery in the life of a jazz musician is just where this style comes from. Clearly, its not in the notes, because anybody can play a given sequence of notes. The infinite line of monkeys will eventually come up with the exact composition Round Midnight, only it will take a very long time. Its not in the technical mastery, or speed, because often the fastest players are the most boring to listen to.

Why doesnt todays education lead to the development of style?

First of all, we are too often trained to listen without hearing. Not just that we often dont take the time to peer with our ears into the heart of the music and

Next page