Sidran - Black Talk

Here you can read online Sidran - Black Talk full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: BookBaby, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Black Talk: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Black Talk" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sidran: author's other books

Who wrote Black Talk? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Black Talk — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Black Talk" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

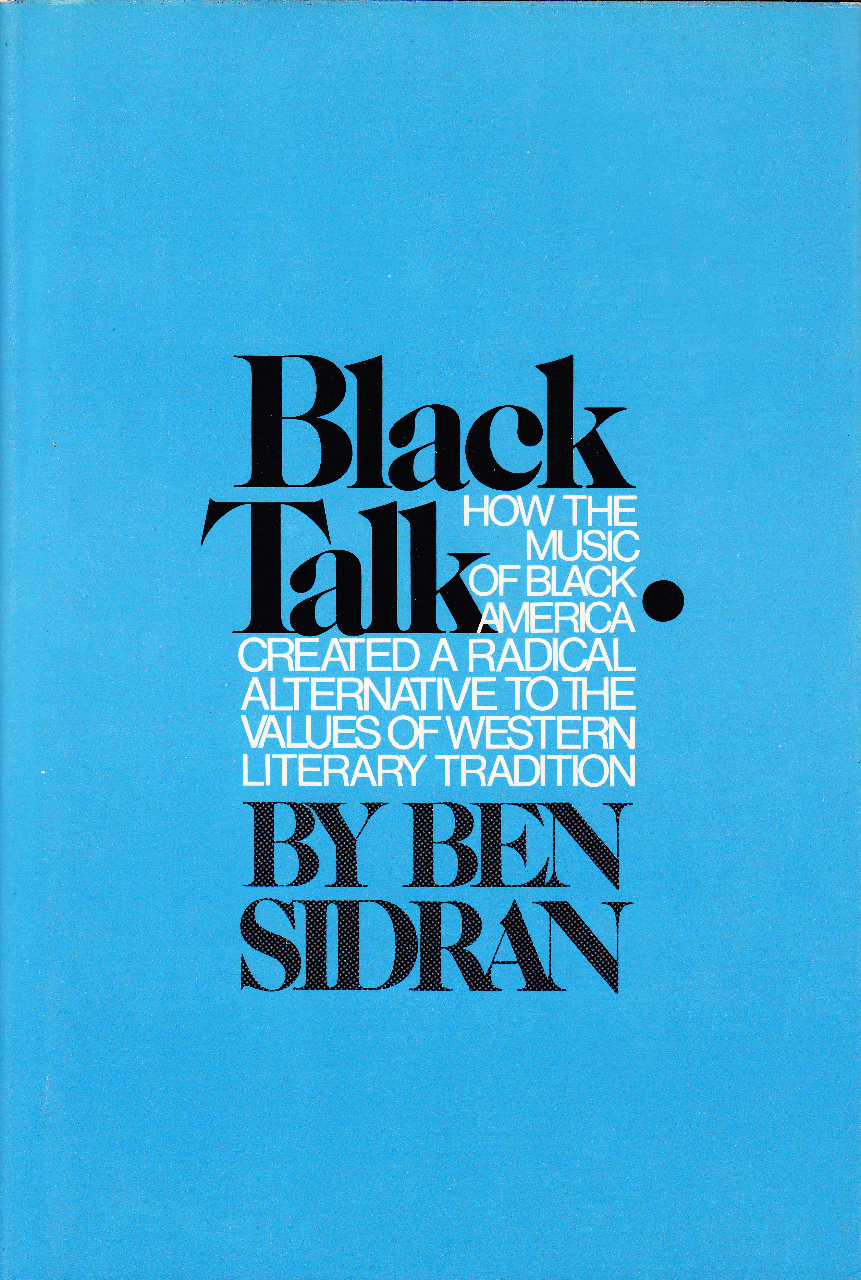

Ben Sidran

BLACK TALK

Copyright 1971, 1981 and 2010 by Ben Sidran

Foreword copyright 1981 by Archie Shepp

All Rights Reserved

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., for permission to quote from Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception

To my father

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introductions

Oral Culture and Musical Tradition: Prehistory

And Early History (Theory),

The Black Musician in Two Americas:

Early History-1917

The Jazz Age: The 1920s,

The Evolution of the Black Underground:

1930-1947,

Black Visibility: 1949-1969,

Selected Bibliography

Footnotes

FOREWORD

I feel privileged to have been asked by Mr. Sidran to introduce Black Talk. First, because I have known the book almost since its initial publication. It has been featured prominently on my book list and I have made numerous references to its concepts in my various lectures and discussions on the subject of African-American music at the University of Massachusetts where I teach.

Let me say, too, that I consider Black Talk one of the most important works on the social process by which Black music is communicated-certainly since the appearance of Blues People by LeRoi Jones (Baraka). For it illuminates the language of Black music, further clarifying, even updating such earlier classics as Muntu and The Myth of the Negro Past. It examines and puts to trenchant analysis certain ideas that have heretofore been only hinted at-even by Black authors. Harold Cruse came closest in his work, Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, when he made a passionate plea for a dialogue among Black intellectuals for the purpose of establishing a Black "critique" or unified position on art, one that would be politically as well as esthetically cogent.

Sidran, however, goes in another direction. More sociologically oriented, he is able to unearth a different aspect of the truth. For he makes reference to the oral tradition, suggesting its retention in the New World and subsequent transference into a socio-musical entity, with numerous political and symbolic implications. And while this is by no means an attempt on Mr. Sidran's part to give us a complete exegesis of traditional tribal experience, he does offer considerable insight into the functional aspects of the "nommo" factors-if I might inject a Bantu reference.

I spoke with Ben prior to writing this piece and our conversation got me thinking about the oral process and just how it functions among Black musicians. John Coltrane is an excellent case in point. I can remember as a young man in my twenties-with Pharaoh Sanders, Rocky Boyd, George Brown (a drummer now living in Europe), saxophonist Marion Brown (no kin to George) and others-requisitioning the great master's time, which he always gave with infinite grace and aplomb. This, of course, would be something less than astounding were it not that Mr. Coltrane's willingness to share his wisdom and profound insights with a younger generation was not exactly the norm among musicians, as is often asserted. In several instances from my own memory I can report that the matter was quite the contrary. Not to say that the oral tradition had stopped working by the time I came along-not by any means. But the old handkerchief over the trumpet keys not only served to confuse would be "white" imitators, but also Black ones. There is a firm belief in this music that (if I may quote Lester Young, second hand) "to join the throng, you've got to make your own song."

Anthropologists and ethnomusicologists use the term "informants" to describe the people who are essential to the transmission of the oral information. The word's unfortunate resemblance to "informers" (which connotes "stool pigeon," someone who is an unwilling-or willing-dupe of another's ploy) is ironic, for this has often been the situation when innocent, untutored people have shared private, esoteric information with self-seeking scholars and recording companies who exploit their subjects for the furtherance of academic research.

Let us consider Mr. Coltrane not as "informant" but as teacher in the highest pedagogic sense, as "guru." In a conversation I had with George Brown a few years ago in Geneva, he reminded me of the reverence and esteem we all had for John and how this came out in our various conversations with him. We were, mind you, not only awed by Coltrane the virtuoso (whose innovations still baffle would-be imitators) but our taciturnity before him was rooted in basic respect, an understanding of the rules regarding "elders." As Brown so poignantly remembered, "We mostly just sat and listened, maybe offering a comment of acknowledgment every now and then. We all recognized our ignorance in the face of his genius."

For a moment I thought back to those early days on Columbus Avenue, where the Coltrane family had moved after coming from Philadelphia. I thought of myself just as George described. This is not to say that we didn't have searching musical questions to ask. But the questions themselves were part of a spiritual matrix in which the personality of the master was more important to the relationship than the rhetorical handling of academic whys and wherefores. It transpired more in the spirit of the training of a Yaruba apprentice carver, than in the creation of a conservatory product.

For example, I remember spending an entire afternoon with John, just listening to him talk about his admiration for Art Tatum, whom he loved (along with Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis) much the same way we loved him. "Art," he said with informed excitement, "would approach a C seventh from the E-fiat chord or even as far away as the F -sharp (an interval of an augmented fourth) and resolve it within a space of four beats." (This makes a total of six half-steps, and if we assume that a seventh has a minor counterpart, there are at least twelve possibilities for harmonic improvisation in this simple one-bar contest.)

Mr. Coltrane was then developing his famous "sheets of sound," in which he did on the saxophone the things he heard on Tatum's piano-taking the conception further. I barely understood at that time the implications of this informal conversation. In fact, it took me years to realize the effect of that single afternoon on my overall approach to saxophone playing.

From a performer's standpoint Mr. Coltrane, like his mentor Parker, had an incredible technical ability, the product of prodigious and painstaking practice. Yet his artistry was less a matter of speed or technical prowess than of a certain passion, born of a sense of discipline and integrity almost mystical, yet integral to Black improvised music at its highest level. His virtuosity was rooted in a tradition that had developed long before Joplin composed "The Maple Leaf Rag."

I believe the fundamental source of the characteristic Black musical genius derives from three essential areas of experience: (1) The Afro-Christian Church; (2) the functional song (here defined as the work song, arhoolie, cries, etc.) as it evolved under slavery; and (3) the various songs, chants; games that come from Black childhood experience.

Prior to World War II most African-American music, though it offered a strong instrumental component, was essentially dance-oriented. And to this extent the prerequisites of "swing" were paramount. Music, as Ellington said, just didn't mean a thing without it-though he himself foreshadowed development of longer, more instrumental forms, even in his early works. But with the coming of the war the cabaret tax on large dance establishments made it prohibitive to hire big bands.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Black Talk»

Look at similar books to Black Talk. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Black Talk and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.