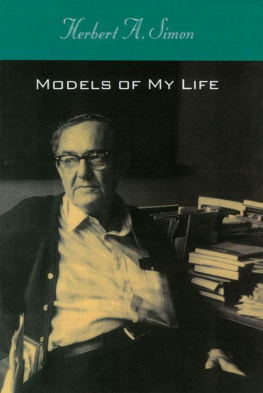

Models of My Life

Models of My Life

Herbert A. Simon

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

First MIT Press edition, 1996

First published in 1991 by Basic Books.

1996 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed on recycled paper and bound in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Simon, Herbert Alexander, 1916

Models of my life / Herbert A. Simon.1st MIT Press ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Basic Books, 1991, in series: The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation series.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-69185-7 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Simon, Herbert Alexander, 1916 . 2. EconomistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

HB119.S47A3 1996

330'.092dc20

[B]

96-21495

CIP

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

ISBN 978-0-262-32658-2 (e-book)

To Dorothea, so aptly named

Preface to the MIT Press Edition

A continuing interest in my autobiography, which has been out of print for several years, brings forth this new edition under the imprint of The MIT Press. I am especially pleased that the book has struck a responsive chord in people, some of them friends, some of them strangers, who find interesting and informative its picture of a life in science. The account of what I have done with my life (and what it has done with me) represents one scientists view of the academic enterprise in general, and the research enterprise in particular: how one pursues a life in science, and the satisfactions (and occasionally frustrations) it can provide. Notice that I say, a life in science, not a life of science, for I have tried to tell the whole story of growing up and living, a story in which science has been a vital part but, for all that, only a part.

A number of readers have told me that the books picture of a scientists life resonated sufficiently with their experiences that they presented copies to their children or their students who were just embarking on such a life or considering it. I hope that those who find it among their holiday or graduation gifts and those who encounter it in their bookstores will be informed (and entertained) but not misled by it. Science has been very good to me, and if they have a vocation for it, it will likely be good to them.

The path I have followed has exposed me to a broad panorama of science. I have wandered widely (always for reasons that, at the moment, seemed compelling, you understand!) from political science and public administration, through economics and cognitive psychology, to artificial intelligence and computer science, with side excursions into the philosophy of sciencesometimes pursuing two or more of these simultaneously. My central interest in decision making and problem solving led me to study the psychological processes of scientific discovery, which, in turn, induced explorations of many domains, especially in mathematics and the physical and biological sciences, that go well beyond the areas mentioned above. So I hope that readers will not find it hard to relate some of the events they meet here to their own favorite sciences. I have also spent many hours and days engaged in the politics of science (I hesitate to call it statesmanship), and particularly in helping to bring the social and natural sciences together so that they can discharge their joint responsibility for informing public policy.

Apart from correcting errors of fact and typography, I have not revised the text of the first edition. The five years since I wrote Models of My Life have been busy and exciting years, in which I have continued to pursue my (lengthening) research agenda, but their flavor is not unlike that of the years just preceding them. (Pages 327331 still describe quite well the domains in which I am active.) I have no startling new truths about Life to announce; my adventures continue to be mainly adventures of the mind, as I am curently eschewing new adventures by airplane. Hence I am content to leave the story in its original form. I hope you enjoy it.

Herbert A. Simon

Pittsburgh, 1996

Acknowledgments

I am deeply indebted to friends who have read and commented on earlier drafts of this book: Mark Harris, Larry Holmes, Richard Kain, Pamela McCorduck, Robert Merton, and my wife, Dorothea. They are not responsible for imperfections in either my Life or my life.

Several parts of my account borrow freely from earlier writings. A chapter-length autobiography in Gardner Lindzey, ed., A History of Psychology in Autobiography, volume 7, provided a matrix that I have greatly expanded into the present book. I am grateful to Gardner Lindzey, the copyright owner, for permission to use this material.

An earlier version of was my Edmund Janes James Lecture of October 10, 1985, given at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; it was issued under the title Charles E. Merriam and the Chicago School of Political Science by the Department of Political Science at that university (copyright 1987 Herbert Simon).

The conversation with Jorge Luis Borges in took place in Buenos Aires in December 1969, and a Spanish report of it was published in the January 1970 issue of Primera Plana, published by the Sociedad Argentina de Informatica e Investigacin Operativa (SADIO). The English version reproduced here is my own retranslation from the Spanish (the conversation was in English).

draw upon the historical appendix to Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon, Human Problem Solving, copyright 1972 (pages 87389) reprinted by permission of Prentice Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

The first portion of , dealing with my 1972 trip to China, is based on Maos China in 1972, published in Items 27 (no. 1): 1973, and reprinted with permission from the Social Science Research Council.

, titled My Life Philosophy, appeared in The American Economist 29 (no. 1): 1985, and this modified version is reproduced with the permission of that journal.

In 1987, when my colleagues in the Psychology Department told me that they intended to make that years Spring Symposium a Festschrift to honor my seventy years, I asked leave to give a paper at the Symposium on science as problem solving. The Afterword is based on that paper The Scientist as Problem Solver, which appeared in David Klahr and Kenneth Kotovsky, eds., Complex Information Processing: The Impact of Herbert A. Simon, and is reprinted with permission of the publisher, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

The letter from the late Chancellor Lawrence A. Kimpton of the University of Chicago in is reprinted with the permission of the University of Chicago.

The two letters from Bertrand Russell in are reproduced with permission from the Editorial Committee of the Bertrand Russell Archives. Copyright of the previously unpublished letter (November 2, 1956) is held by Res-Lib Ltd.

I received immense editorial help in preparing the Basic Books edition from Linda Carbone, an implacable enemy of prolixity, unclarity, and dullness. Deborah Cantor-Adams of the MIT Press and my assistant, Janet Hilf, have been similarly indispensable in helping to prepare the present edition.

Parler srieusement, cest parler

comme on se parle soi-mme.

Comme lon parle au plus prs.

Paul Valry, Instants

Introduction

PROUST titled the final volume of his lifework The Past Recaptured. But, of course, the past cannot be recaptured. Memory is overlaid with later memory, mangled by self-justification and self-pity, guarded by self-interest, rent by great gaps of forgetfulness. Proust did not recapture his past, but reconstructed it, marvelously, with an insight he most surely did not have as he lived it.

Next page