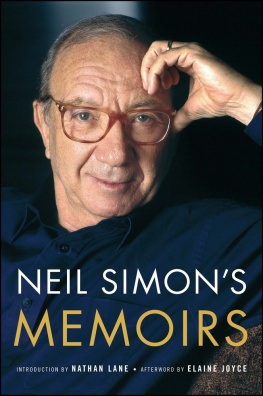

Simon - Neil Simon rewrites a memoir

Here you can read online Simon - Neil Simon rewrites a memoir full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1996, publisher: Simon & Schuster, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Neil Simon rewrites a memoir

- Author:

- Publisher:Simon & Schuster

- Genre:

- Year:1996

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Neil Simon rewrites a memoir: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Neil Simon rewrites a memoir" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Simon: author's other books

Who wrote Neil Simon rewrites a memoir? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Neil Simon rewrites a memoir — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Neil Simon rewrites a memoir" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For their encouragement and care in guiding me through the dangerous shoals of writing prose, I wish to thank Michael Korda, Charles (Chuck) Adams, Gypsy da Silva and Virginia Clark. Also to Morton Janklow for pointing me there.

1

IN THE SPRING OF 1957, I was unhappily in California working on a television special. I was thirty years old and knew that if I didnt start writing that first Broadway play soon, I would inevitably become a permanent part of the topography of the West Coast. The very thought of it jump-started me to my desk.

I sat at the typewriter and typed out ONE SHOE OF F, all in caps and putting a space after each letter and a double space after each word, trying to picture what it would look like up on a theater marquee. Four spaces down, in regular type, came A New Comedy. I sat back and studied it. Not a bad start for a first play. Then I suddenly wondered: when they wrote together, did George S. Kaufman type this out or did Moss Hart? No, it must have been Hart. He was the eager young writer poised behind the trusty old Royal machine while Kaufman, the seasoned old pro, would be lying across a sofa in his stockinged feet munching on his handmade fudge, bored by such prosaic labors as manual typing. Kaufman had probably put in enough time punching the keys back in the old days when he was drama critic for The New York Times. How I envied young Moss Hart being in the same room with the great Kaufman, knowing he would be guided through the pitfalls of play writing much as any cub reporter would feel the security of marching behind Henry M. Stanley as he guided his pack-bearers across the African plain in search of the great missionary, and then, upon finding him, having the coolness and gift of a great journalist to put quite simply and memorably, Dr. Livingstone, I presume?But, I had no Henry M. Stanley to teach me the impact of brevity in great moments. As a matter of fact, I had no George S. Kaufman, no fudge, no nobody. I had me. Not only had I not written a play before, I had never written anything longer than twelve pages, which was all that was required for a TV variety sketch back in the mid-1950s. Even that was a major step up from the one-liners I used to write with my brother, Danny, when we were earning our daily bagels working for stand-up comics and sit-down columnists.

Now I was faced with 120 pages to feed, complete with characters, plots, subplots, unexpected twists and turns, boffo first-act curtain lines, rip-roaring second-act curtain lines, and a third act that brought it all to a satisfying, hilarious, and totally unexpected finish, sending audiences to their feet and critics to their waiting cabs, scribbling on their notepads in the darkness, A Comic Genius Hit New York Last Night. At least Lindbergh had the stars to guide him. I didnt even know how to change the typewriter ribbon. Nevertheless, I pushed on.

I was about to jump four spaces down to write the simple word by, no caps, this to be followed by my name a little farther down the page, when it suddenly occurred to me that of the only two lines I had written so far, one of them was inordinately stupid. A New Comedy I had seen this printed in the theater section of the Times for eons, seen it on billboards and marquees all over New York, and it never hit me until just now A New Comedy? Was this to make it clear to the audiences they should not confuse this with An Old Comedy? Shouldnt it just be A Comedy? And even that was a matter of opinion. A century ago, Chekhov had written A Comedy before such plays as The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard. According to his biographers, however, neither of those plays was ever staged as a comedy during his lifetime, much to his beleaguered protests. So much for interpretation. Novels never made any such pronouncements. My copy of War and Peace never said, A New Epic Drama by Leo Tolstoy. Never once in any movie theater did I see the screen titles come up and read, Some Like It Hot, A New Farce by Billy Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond. If novelists trusted their readers to discover what their books were about and filmmakers didnt feel it necessary to spell it out, why do playwrights or their producers hold their audiences in such low esteem? Would I be brave enough to break with tradition? Since I had not yet typed in by and Neil Simon, I didnt feel I had enough experience.

I plunged back into intensive work and finished typing in by and Neil Simon. I sat back and studied my work so far. It was good but something was missing. It did not occur to me to type in the lower right-hand corner of the page 1st Draft, Oct. 15, 1957. I never assumed there would be a second draft or, God forbid, a third draft. Wasnt writing a hundred and twenty pages accomplishment enough? Surely I would change a few words here and there, possibly cut a few lines or add some last-moment inspirations of wit, but new drafts? It was unimaginable. Did Shakespeare do rewrites? How? He obviously wrote in longhand on cheap parchment with a scratchy quill. His plays ran four hours and he wrote thirty-seven of them, not to mention the sonnets, letters to actors and producers, love notes to Anne Hathaway, and excuses for delayed payments to roof thatchers and the local dung heating suppliers. The quills needed for this enormous output alone must have taxed the poultry growers of the region to their capacity. The acting roles in each of the plays numbered in the thirties, which meant at least that number of additional scripts, not to mention those for stage managers and understudies. Even if he had friends and apprentices quill-copy each play to make up the additional scripts, it must have meant thousands upon thousands of naked fowl running around central England. The time, the labor, the costs, and the wear and tear of stress on Bill Shakespeare would certainly inhibit and prohibit the luxury of rewrites. He was certainly in the top three of the worlds greatest geniuses and if he had to do without rewrites, why should I worry about them? But I did. I typed in 1st Draft, Oct. 15, 1957, took it out of the typewriter, put it on my desk face down, inserted the next blank piece of paper in the machine, and said to myself, Now how do you begin a play?

All I had was the subject. Not a story, not a plot, not a theme, just a subject. Actually, the subject was my third priority. Number two on my list was a desire to write for Broadway. Number oneand this was my dominating motivation, far and above all the otherswas a desperate and abiding need to get out of television. In the mid-1950s, when some great electronic genius picked up the coaxial cable that would interconnect all television stations from coast to coast, plugged it into a wall socket, and saw that it worked, my days in New York were numbered. Television, like the film industry some forty years prior, was going west with all the young men. California had the largest studio space, the sun for shooting outdoor scenes, and the smog for shooting London scenes. It all seemed to make sense. Not to me, and certainly not to my wife, Joan. We loved New York. Life without New York was inconceivable. I grew up on the streets of Washington Heights in upper Manhattan; Joan was raised a horses canter away from Prospect Park in Brooklyn and about a home runs length away from Ebbets Field. I was a Giants fan; she, of course, was a Dodger fanatic. We were the Montagues and Capulets of baseball, who found true love despite this insurmountable barrier. When the Polo Grounds was finally toppled into dust and Ebbets Field was dismantled brick by brick, downing a vial of poison each was not totally out of the question. Moving from New York to California was. If possible, Joan was even more adamant than I was. To her, New York was the center of the universe. It was the ballet, the theater, the museums,

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Neil Simon rewrites a memoir»

Look at similar books to Neil Simon rewrites a memoir. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Neil Simon rewrites a memoir and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Simon Brett [Simon Brett] - Mrs. Pargeter’s Point of Honour](/uploads/posts/book/142155/thumbs/simon-brett-simon-brett-mrs-pargeter-s-point.jpg)

![Simon Brett [Simon Brett] - Mrs. Pargeter’s Package](/uploads/posts/book/142153/thumbs/simon-brett-simon-brett-mrs-pargeter-s.jpg)