THE

SPIRAL

NOTEBOOK

Copyright Stephen and Joyce Singular 2015

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Cover design by Michael Kellner

Interior design by Elyse Strongin, Neuwirth & Associates, Inc.

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-644-5

To Eric

CONTENTS

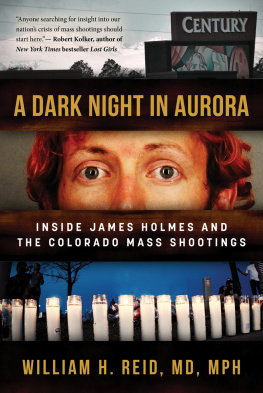

On the morning of July 20, 2012, we drove to the Aurora apartment of James Holmes and then to the Century 16 movie complex. Several hours earlier at this theater, Holmes had unleashed the largest mass shooting in U.S. history, and news reports of the event were still breaking across the country and around the world. Since his living space and the crime scene were only a few miles from our Denver home, we wanted to see the locations for ourselvesmarking the beginning of an investigative journey that would last for the next two and a half years.

The first people we interviewed were Holmess neighbors, who were standing a few hundred yards from his blocked-off apartment building, now wired with explosives and ready to blow. As the bomb squad worked to defuse the situation, the locals stared at the building in bewilderment and talked about what had happened in the theater. We continued on to Century 16, and in an adjacent parking lot we spoke to moviegoers whod survived the massacre. Police had just released the witnesses from their custody.

Over the next thirty months, we attended all of the significant legal proceedings for Holmes. These included motion hearings, evidentiary hearings, hearings on the spiral notebook itself, and those on psychiatric issues, the death penalty, and the debate over criminal sanity versus insanity. Most importantly, in January 2013 we sat through the preliminary hearing, where the prosecution outlined its case against Holmes. We heard two full days of police testimony, which helped us to reconstruct a timeline of Holmess movements leading up to, during, and following the massacre. This process was aided by our own investigations and by numerous journalistic sources, both local and national, devoted to uncovering and tracking Holmess behavior. In addition to this, we conducted personal interviews with many people and businesses in and around the Anschutz CU campus, most speaking to us under the condition of anonymity. We were able to talk with several staff members in the graduate department of CU, again under the condition of anonymity. None spoke directly about the case itself, but only about Holmess routine at the school, offering a sense of who he was before he became infamous. We visited Anschutz and retraced Holmess steps around the campus. We saw his classrooms, his lab, and where hed had his therapy sessions in the spring of 2012. In 2013 and 2014, we sat in on the kinds of lectures on the brain and mental illness that Holmes might have attended had he not been incarcerated. We went to the tavern where he drank in the evenings and to the places in his neighborhood where he shopped or ate his meals. Many years before the massacre, wed watched films at the theater where the shootings occurred, and we returned to the movie complex after it had been remodeled and renamed following the tragedy. All of these things provided us with a more intimate feeling for the young mans life as he made his descent into violence during his year in Aurora.

Starting in the summer of 2012 we also began a series of interviews that lasted over two years and included psychologists, psychiatrists, first responders, psycho-pharmacologists, private investigators, teachers, and many, many young people throughout the nation. Because the thousands of pages of legal documents the shootings had generated were sealed and all of the principals in the case were under a gag order, we couldnt approach this as a true crime story and put together a conventional narrative of Holmess actions, as wed done in many previous books. Instead of writing about one mass shooter, we started to explore the society and the generation that had produced not just Holmes, but so many other young male killers. This turned out to be our deeper interest, partially because we had a son not much younger than Holmes himself. By taking our investigation outside of the courtroom, we stumbled onto a much larger stage.

During those thirty months of investigation, we talked to anyone whod speak with us about the mass-shooting phenomenon: from teenagers to those in their eighties and nineties; from people we met at social gatherings to those we ran into at coffee shops. Everyone in America is a part of this story, and most everyone, if probed a little, has something to say about it. Our job, first and foremost, was to start the conversation. Because of the impact and reach of social media, most young people were much more comfortable and much more open when speaking with us if their names werent used. All of these voices, whether theyre in the book or not, make up the fabric of this story. They offer a portrait of America passing through a scourge of violence new to our national experience.

Its both reflexive and normal to recoil from the phenomenon of mass shootings. But that reflex hasnt solved the problem or made it vanish. In the summer of 2012, we decided to move toward this phenomenon rather than away from it to see if we could learn something new about ourselves, our own family, and our society.

THE

SPIRAL

NOTEBOOK

You Dont Understand How I Grew Up

Our sons formative years in Denver were bookended by two mass tragedies. The first was at Columbine High on April 20, 1999, when a pair of teenagers walked into the school and opened fire, killing twelve students, a teacher, and themselves. This happened about fifteen miles from our home when Eric was five and too young to understand the significance of the event. But he was not too young to pick up on the feeling in the city or our house that dayone of profound sadness. Words seemed inadequate to the occasion; nobody knew what to say and it was uncomfortable to make eye contact on the street. The violence was close enough to send a message to everyone: Something is fundamentally wrong and this is the end result of it. Dont take anything for granted, including your next breath.

The second bookend was the Aurora Theater shooting, seven miles from our home, unleashed just after midnight on July 12, 2012. Eric was almost nineteen and a sophomore at the University of Colorado, studying sociology. The morning following this massacre, which left twelve dead and seventy others wounded, we decided to drive out to the crime scenes. We had, after all, spent the past two decades working as investigative journalists and writing books about American violence. Our interest was in understanding more about the psychology of those who committed murder, but wed always covered these events from a distanceas reporters conducting interviews or as observers sitting in courtrooms. That distance was now gone. The carnage in Aurora was even closer to us than it had been at Columbine. Our family had watched many films together in Theater Nine of the Aurora movie complex, where the shootings had taken place.

Next page