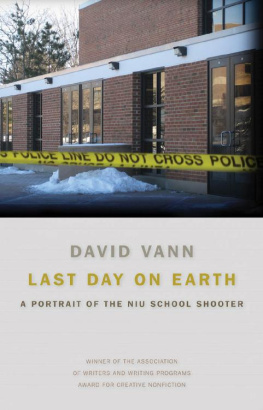

LAST DAY ON EARTH

WINNER OF

THE ASSOCIATION OF WRITERS

AND WRITING PROGRAMS

AWARD FOR

CREATIVE NONFICTION

LAST DAY ON EARTH

A PORTRAIT OF THE NIU SCHOOL SHOOTER

DAVID VANN

This is a work of creative nonfiction. It draws from primary source materials including police files and other documents, as well as many hours of interviews. The author has made every effort to reconstruct dialog, scenes, descriptions, and motivations as accurately as possible. Names and identifying characteristics of some persons have been changed to protect their privacy.

Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2011 by David Vann

All rights reserved

Set in Scala

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

11 12 13 14 15 C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vann, David.

Last day on earth : a portrait of the NIU school shooter / David Vann.

p. cm. (Association of writers and writing programs award for creative nonfiction)

ISBN 978-0-8203-3839-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Kazmierczak, Steve. 2. Mass murderIllinoisDe Kalb.

3. Youth and violenceIllinoisDe Kalb. 4. School shootingsIllinoisDe Kalb. 5. Campus violenceIllinoisDe Kalb.

6. Northern Illinois UniversityStudents. I. Title.

HV6534.D434V36 2011

364.15234092dc23

2011018019

Parts of this book originally appeared in Esquire, Mens Journal, Esquire UK,

and the Sunday Telegraph.

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-4210-8

Nothing human is foreign to me.

TERENCE

(195159 BC)

I tried to peer around the podium to get a look at him, but the minute I saw him, he turned and saw me. He turned and fired, and he pulled the trigger of the Glock multiple times. He just kept shooting me. I got hit right in the head. It felt like getting hit with a bat. As I fell to the floor face first, all I could think was, I got shot and Im dead. I hit the floor with my eyes closed and a ringing sound in my ear, and I thought this was literally the sound of my dying, going into the darkness.

BRIAN KARPES,

survivor of the NIU school shooting,

February 14, 2008

LAST DAY ON EARTH

AFTER MY FATHERS SUICIDE, I inherited all his guns. I was thirteen. Late at night, I reached behind my mothers coats in the hall closet for the barrel of my fathers .300 magnum rifle. It was cold and heavy, smelled of gun oil. I carried it down the hallway, through kitchen and pantry into the garage, where I turned on the light and gazed at it, a bear rifle with a scope, bought in Alaska for grizzlies. The world had been emptied, but this gun had a presence still, an undeniable power. My father had used it on deer. It sounded like artillery, would tear the entire shoulder off a deer hundreds of yards away. I pulled back the bolt, sighted in on a cardboard box across the garage. A box of track for an electric train, and one small rail sticking up filled the scope. I held my breath as my father had taught, squeezed carefully, slowly, heard a metallic click.

With a screwdriver, I separated stock from barrel. I put both pieces down the back of my jacket, cinched under my belt. They stuck out from my collar behind my head but were mostly hidden. I wheeled my bicycle, an old Schwinn Varsity ten-speed, out the back door and through a gate in our fence.

Our neighborhood was silent at 3:00 a.m. Cold still in early April, 1980, a light mist in the air. I huffed up a steep hill in low gear, hot in my fathers jacket, starting to sweat by the time I hit the top. Then coasted down the other side, my ears cold. Big houses, trim lawns, but several streetlights knocked out. Broken somehow, a few remaining shards of glass on the pavement below.

Up the next hill, I pulled off to the side, an undeveloped lot, tall grass and a few oak trees. I hid my bicycle behind one of them and hiked away from the houses until finally I hit a small clearing and had a view. Much of Hidden Valley, in Santa Rosa, California, lay before me.

The rifle went together quickly, and I pulled three shells from my pocket. So much powder packed into the brass. Magnum means too much powder, a bullet sent at much higher speed. I pushed all three shells into the magazine, pulled back the bolt, clicked off the safety. Sat back against the hillside with my feet planted wide, elbows on my knees, forming a base.

Through the scope, I traced houses. Went along their bedroom windows, held crosshairs on their front doors, on taillights of cars in their driveways. Finally zeroed in on a streetlight, rounded and smooth and bright, large in the scope. I could see the bulb inside. Never closer than 100 yards, most of the time two or three times that far, and most of the time, I didnt pull the trigger. It was enough simply to imagine. But sometimes that wasnt enough. Sometimes I wanted more. On those nights, I felt the blood in my temples, a pounding my father had called buck fever when we hunted deer, my breath gone, my heart become hard as a fist. I tried to steady, squeezed slowly, and felt afraid of the shock to come.

When I fired, the rifle kicked so hard it sometimes blew me flat on my back. Id had a .30-.30 since I was nine, was used to rifles, but the .300 magnum was outrageous. If I was lucky, Id hit my target and also stay upright. Nothing was more beautiful to me than the blue-white explosion of a streetlight seen through crosshairs. The sound of itthe pop that was almost a roar, then silence, then glass raincame only after each fragment and shard had sailed off or twisted glittering in the air like mist.

Dogs would bark, lights come on. And if anyone in my field of view parted their curtains to look out, I pulled back the bolt to put a new shell in the chamber, sighted in. A mans face, centered in the crosshairs, lit from his bedside lamp, the safety off and my finger held to the side, just above the trigger. I had done this with my father. When he spotted poachershunters trespassing on our landhe would have me look at them through the scope.

These were not my darkest moments that year. I imagined many things, even shooting my classmates at school. I lived a double life. A straight-A student who would become valedictorian. In student government, band, sports, etc. No one would have guessed.

So when I read about Steve Kazmierczak, a Deans Award winner who killed five students and himself at Northern Illinois University on Valentines Day 2008 and wounded eighteen others, I wondered. He was an A student. His friends and professors couldnt make any sense of what had happened. This wasnt the Steve they knew. I had never been interested in mass murderers before and couldnt have imagined reading a book about one, much less writing one, but I wondered whether Steve might offer a view into why it is that sometimes the worst part of us wins out. Why had I not ended up hurting anyone? How had I escaped, and why hadnt he?

As I investigated Steve for Esquire, as I gained access to the full fifteen-hundred-page police file that had been withheld from all othersfrom the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Washington Post, CNNI found the story of someone who really did almost escape, who almost managed to avoid becoming a mass murderer, someone trying to make something of himself after a wretched childhood and mental health history, someone attempting the American Dream, which is not only about money but about the remaking of self. His life had been far more terrible than mine, his successes a far greater triumph, but through him I could understand, finally, the most frightening moments of my own life and also what I find most frightening about America.

Next page