All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Kotlowitz, Alex, author.

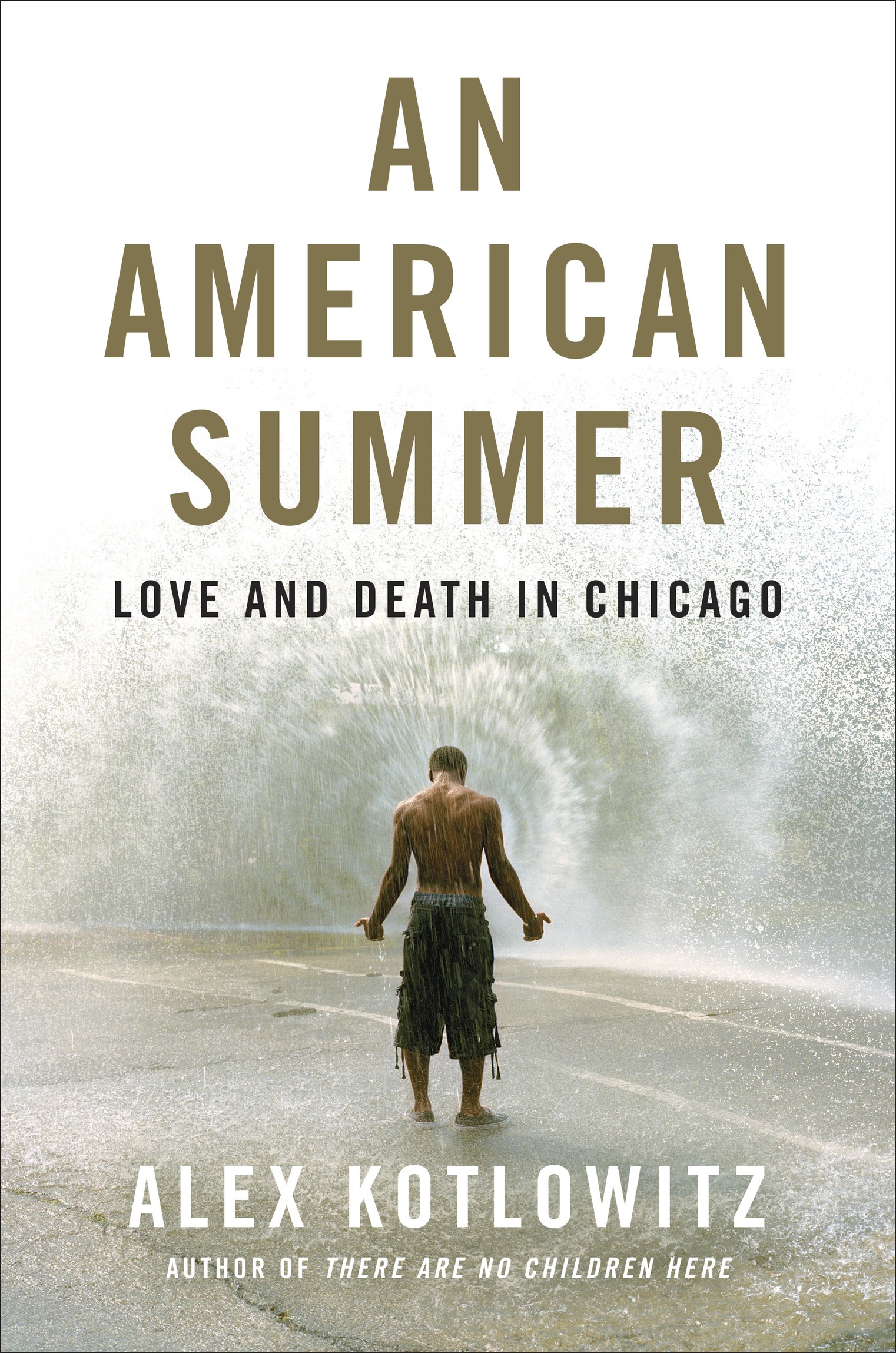

Title: An American summer : love and death in Chicago / by Alex Kotlowitz.

Description: First edition. | New York : Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014026 (print) | LCCN 2018014741 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385538817 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385538800 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : Youth and violenceIllinoisChicago. | Violent crimesIllinoisChicago. | Victims of violent crimeIllinoisChicago. | African American youthIllinoisChicagoSocial conditions21st century. | African AmericansIllinoisChicagoSocial conditions21st century. | Chicago (Ill.)Social conditions21st century.

Classification: LCC HQ 799.2. V 56 (ebook) | LCC HQ 799.2. V 56 K 68 2019 (print) | DDC 364.150835/0977311dc23

Prelude to a Summer

Near midnight on August 19, 1998, the phone rang, an unusual occurrence at my parents home in upstate New York, where I was visiting with my wife and infant daughter. I got out of bed and scrambled to the hallway to grab the phone. The voice on the other end sounded familiar, but I couldnt quite place it. Its Anne Chambers, she said. Anne was a Chicago violent crimes detective whom I knew. She told me she was calling from the kitchen in our home in Oak Park, a suburb bordering Chicago. She told me that Pharoah was there with her, and that he may have been involved in a murder. My legs buckled. I sat down to catch my breath.

This was the Pharoah from my book There Are No Children Here, a boy who stepped cautiously, who loved school, and who was so charming and vulnerable that adults went out of their way to protect him. Shortly after the book came out, Pharoah, who had grown up in one of the citys housing projects, had moved in with mefor what I thought would be a short period. Id helped get him into Providence St. Mel, a college prep school on the citys West Side, and he was struggling, understandably. He couldnt find quiet in his first-floor public housing apartment, as rivers of people flowed in and out daily, mostly family and family friends. He called and told me he just wanted to catch up with his schoolwork. Could I stay with you, just for a while? he asked. Maybe a week or two? I was single at the time, unencumbered and with a spare bedroom, so I invited him to stay. Though only twelve, he knew what he needed. He brought with him a garbage bag filled with clothesand his school backpack. Those two weeks turned into six years.

When I got married, Pharoah walked my wife, Maria, down the aisle, along with her dad. We moved to Oak Park as we wanted to be near his school, and we figured it was a community that wouldnt look askance at this unusual arrangement. His adolescent years were rocky. I didnt anticipate how this living situation would pull at his sense of identity. While his mother, LaJoe, supported his decision to live with Maria and me, others in his family didnt. One time his mother called and after leaving a message forgot to hang up, and so on my answering machine I listened to a five-minute rant by a friend of their family berating LaJoe for letting Pharoah live with a white couple. He dont belong there, the woman told LaJoe. He aint white.

I knew it had to be hard for Pharoah. He undoubtedly heard these harangues as well. Its tough enough to be a teen in the best of circumstances, grappling with who you are and who you want to be, and here Pharoah had to figure out who he was while living with two white adults who were not related to him by blood, who were not his parents, who were not even his legal guardians. In particular, he had an older brotherI gave him the pseudonym Terence in the bookwho clearly resented Pharoahs decision to live with us, and so he would try to pull Pharoah into his activities in the street. There was also a measure of opportunism here, as he knew that Pharoah, who had never been in trouble with the law, would not likely draw the attention of the police. It felt like a tug of war, and I often felt on the losing end. At one point Pharoah knew he had to get away, to find some reprieve from these forces pulling at him, and so at his request we sent him to a boarding school in Indiana, a military academy where he had attended summer camp.

A week after he left, I was tidying up his bedroom, picking clothes off the floor, making his bed, and finally cleaning his closet, where on the top shelf I noticed a worn black leather bag the size of a medicine ball. I reached to pull it down. It was bloated with cash. I mean lots of cash. Tens. Twenties. Hundreds. All of it stuffed into the bag without much concern for appearance or organization. I knew right away that it belonged to Terence, that he had probably asked Pharoah to hold it for him. I called a friend, an attorney, for advice. His words were simple: Get rid of it. He called me back a few minutes later and clarified: I dont mean throw it away. So I called Terence and told him I had something of his which he needed to retrieve. He refused to come to Oak Park, worried that Id set him up with the local police, so I agreed to meet him on the citys West Side, and there in the middle of a one-way residential street in the early afternoon, in the open so that we both felt protected, I handed over to him what turned out to be somewhere in the neighborhood of $18,000. (Terence later accused me of taking $300 from the bag, but thats another story.)

This is what Pharoah was up againstand what we were up against as well. Pharoah got kicked out of the boarding school for selling marijuana and eventually graduated from our local public school. He was accepted at Southern Illinois University and had decided not to visit New York with us during this summer trip because he wanted to get ready for school. Classes began the following week. And then I got this call.

I knew the detective, Anne Chambers, from my time reporting There Are No Children Here. Anne, whom everyone in the neighborhood called Mary (for reasons I never could discern), had been a member of the plainclothes tactical unit in the neighborhood and had a reputation as a fair-minded officer. She was tough, but cared deeply about the kids. She was a single mother, and we used to talk about her son, who at the time was headed off to Harvard with ambitions to be a police officer. She pleaded with him to do something different.

Heres what she told me in that short midnight phone call: Pharoah had taken a taxi from our house to his mothers home on the West Side, and when the cab pulled up, two young men pulled Pharoah out of the backseat and then jumped in. One of them held a pistol to the cabbies head, demanding his money. The cabbie must have panicked, and when he pressed down on the accelerator, one of the assailants shot him in the back. Anne told me that some detectives suspected Pharoah might have set up the driver. Fortunately, Anne knew Pharoah from her time in the projects and knew that he wasnt that type of kid. I told her that I, too, couldnt fathom Pharoah pulling such a stuntthough privately I worried that maybe his brother had put him up to it.