B Y A LEX K OTLOWITZ

T HERE A RE N O C HILDREN H ERE

T HE O THER S IDE OF THE R IVER

All dates, place names, titles, and events in this account are factual. However, the names of certain individuals have been changed in order to afford them a measure of privacy.

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, FEBRUARY 1999

Copyright 1998 by Alex Kotlowitz

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday in 1998. The Anchor Books edition is published by arrangement with Nan A. Talese / Doubleday.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as follows:

The other side of the river: a story of two towns, a death, and

Americas dilemma/Alex Kotlowitz.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Saint Joseph (Mich.)Race relationsCase studies. 2. Benton Harbor (Mich.)Race relationsCase studies. 3. Hate crimesMichiganSaint JosephCase studies. 4. Murder victimsMichiganSaint JosephCase studies. 5. McGinnis, Eric, d. 1991. I. Tide.

F574.S26K68 1998

977.411dc21 97-18247

eISBN: 978-0-307-81429-6

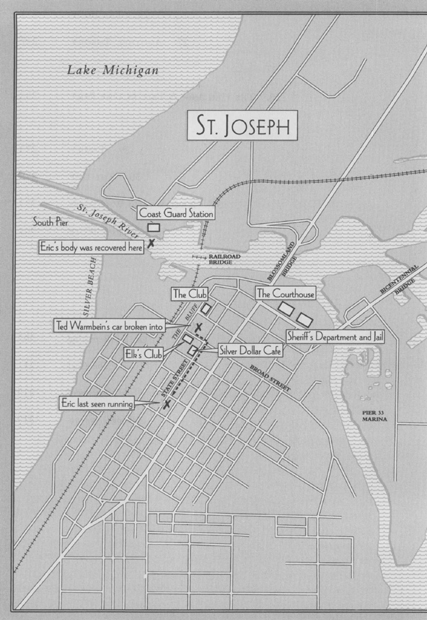

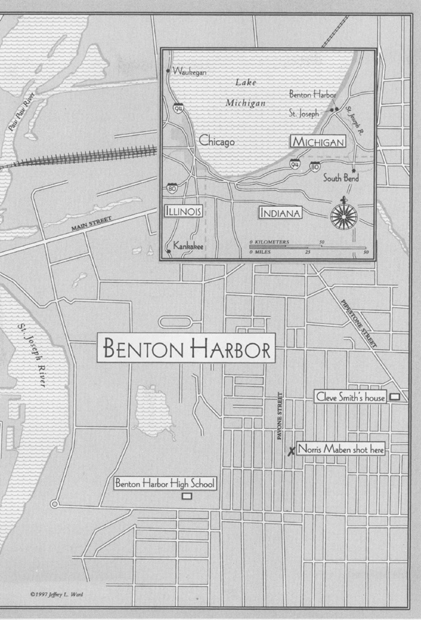

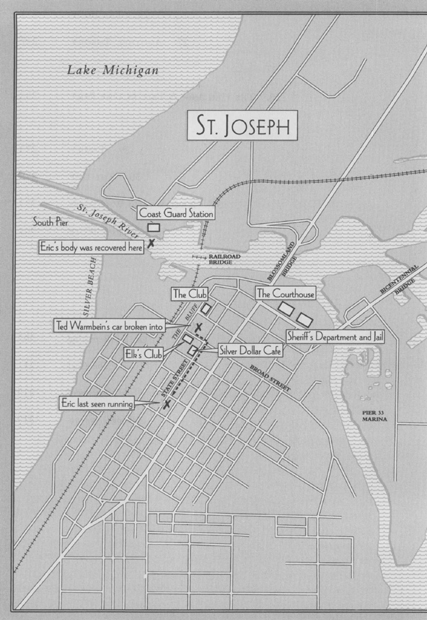

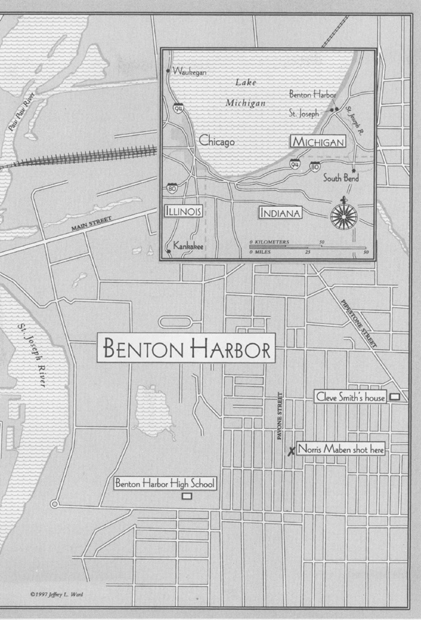

Map designed by Jeffrey L. Ward

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

For Maria

And in memory of my mother,

Billie Kotlowitz

C ONTENTS

1.

T HE B ODY

T his much is not in dispute.

On Wednesday, May 22, 1991, at the days first light, a flock of seagulls noisily abandoned their perches along the two cement piers jutting into Lake Michigan. Like rambunctious schoolchildren, they playfully circled above the mouth of the St. Joseph River here in southwestern Michigan, absorbing the warmth of the new days sun. The seas were calm; the sky, partly cloudy.

Almost exactly one hour later, first-year Coast Guard seaman Saul Brignoni, hosing down a concrete walkway alongside the river, teasingly shot a blast of water at a covy of gulls resting on the embankment and spotted what appeared to be a muddy strip of driftwood floating twenty yards from where he stood. Minutes later, he received a cryptic radio call from the crew of a nearby dredging boat. We got something out here you might want to take a look at.

Brignoni and two colleagues pushed off in their twenty-two-foot Boston Whaler and on closer inspection discovered that the flotsam was the bloated body of a fully clothed teenage black boy. Using a seven-foot-long boat hook, they carefully prodded the discolored corpse onto a large metal litter, turning their heads to avoid the putrid gases that rose from the body, along with the early morning mist from the river.

They then motored back to shore, where they laid the body, face down, on the wooden deck by their barracks and doused it with a nearby hose, cleansing it of some of the river silt. Three St. Joseph police officers soon arrived. While two asked questions of the Coast Guardsmen, making certain to stay upwind of the body, the third officer circled the corpse like a buzzard over its prey, snapping pictures with a 35-millimeter camera. After getting shots of the boys short-sleeved shirt, a blue-striped baseball jersey that read MCGINNIS , Detective Dennis Soucek had his fellow officers carefully turn the body over. He knelt to get close-ups, focusing on the dead boys stonewashed USED jeans, a popular brand, which were unbuckled and unzipped, exposing blue-striped bikini shorts. He snapped shots of the victims upper body, the arms and hands still caked with mud; the skin, yellowish, almost green in places, was scraped away on the left forearm. He took photos of the boys head, which was so swollen that the face looked separated from the skull, as if someone had stuffed cotton in the cheeks, the chin, the forehead, and every other part of the head. Only the ears retained their normal size, and in proportion to the other features seemed small and insignificant. The red lips puckered out like a fishs, and there were marks around the neck, two bloody lines that looked like rope burns. There were other matters the camera caught as well: a silver ring with a turquoise stone, a pinky fingernail painted pink, and unlaced high-top Nikes.

Nearby, Jim Dalgleish, a weedy-looking reporter for the Herald-Palladium, the local newspaper, turned his eyes from the scene, his worn Nikon hanging around his neck. Dalgleish, who, like other reporters at the small paper, doubled as a photographer, had heard over the police radio about a floater in the river and had sped over in his pickup. Drownings are common occurrences around here, sometimes as many as three to four in a year. The area, after all, is surrounded by water. The St. Joseph River slices through the county, its languid surface hiding a sometimes tricky current. The narrower and shallower Paw Paw River feeds into the St. Joseph just upstream from the Coast Guard station; its mucky bottom once devoured a car that had swerved off the road, trapping the driver. And just two hundred yards downstream from the Coast Guard station, the St. Joseph empties into Lake Michigan, which at times can rise up in a fury, whipping eight-to-ten-foot swells onto the two piers. The force of those waves has swept fishermen and foolhardy teens into roiling water where even the strongest of swimmers have a difficult time staying afloat. Dalgliesh, who hadnt the stomach to look at the puffed-up bodies of floaters, only glanced at this particular corpse; he did snap some photos after it was placed on an ambulance stretcher, a white sheet covering it from head to toe.

The body was taken to Mercy Hospital for an autopsy. The incident was, the police believed, probably a drowning.

L ike a swollen snake, the St. Joseph River lazily winds its way north from Indiana through the hilly cropland of southwestern Michigan, eventually spilling into the clear waters of Lake Michigan, where it is 450 feet across at its widest. It is here, near its mouth, that this otherwise undramatic chute of water becomes a formidable waterway, not because of its currents but because of what it separates: Benton Harbor and St. Joseph, two small Michigan towns whose only connections are two bridges and a powerful undertow of contrasts.

South of the river on a hill sits St. Joseph, a modest town of nine thousand that resembles the quaint tourist haunts of the New England coast. Vacationers on their way from Chicagoits a two-hour driveto the northern woods of Michigan stop here to browse the downtown mall, shopping at the antique stores, art galleries, and clothing boutiques. Its beach, just a short walk down a steep bluff from the downtown, once boasted an amusement park, but, reflecting todays more environmentally conscious world, now stands bare, its acres of fine sand and protected dunes luring families and idle teens during the summer months. The town is made up of both blue-collar families and professionals, many of whom work at the international corporate headquarters of Whirlpool, one of the areas major employers. In recent years they have been joined by affluent Chicagoans looking for second homes. For those in Benton Harbor, though, St. Josephs most defining characteristic is its racial makeup: it is 95 percent white.