Contents

Page List

Guide

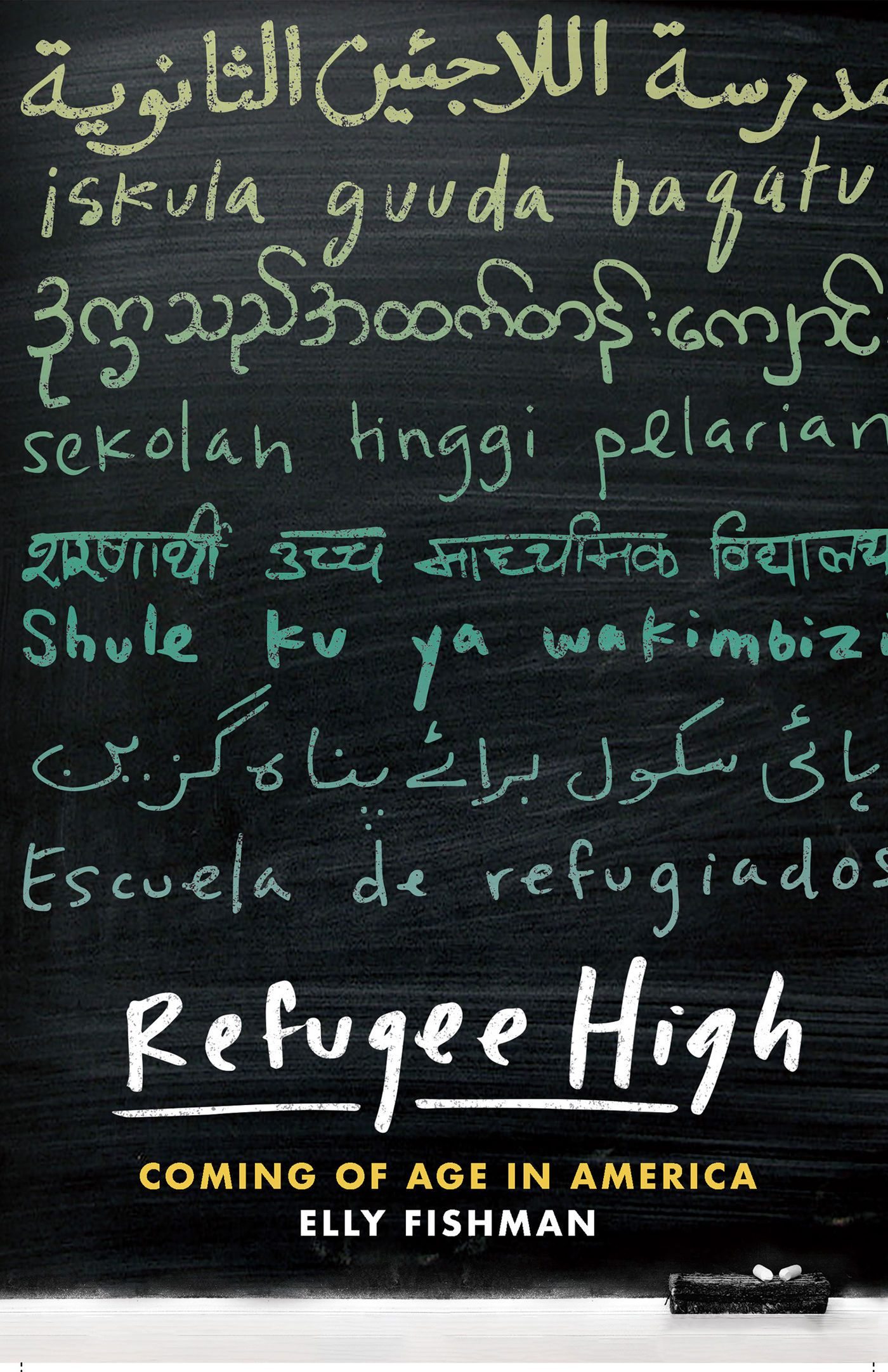

REFUGEE HIGH

REFUGEE HIGH

COMING OF AGE IN AMERICA

ELLY FISHMAN

For my family

CONTENTS

FEATURING

Mariah, a sophomore from Basra, Iraq

Fatmeh, her mother

Farha, her older sister

Khalil, her father

Alejandro, a senior and asylum seeker from Guatemala City, Guatemala

Sergio, his father

Luana, his mother

Jose, his best friend

Belenge, a Congolese sophomore born in Nyarugusu, a refugee camp in Kigoma, Tanzania

Esengo, his friend and a Congolese refugee

Tobias, his father

Asani, his brother

Felix, his friend, neighbor, and a Congolese refugee

Mama Sakina, Felixs mother

Shahina, a sophomore from Yangon, Myanmar

Aishah, her best friend and a Burmese refugee

Zakiah, her mother

Nassim, a freshman from Daraa, Syria

Abdul Karim, a senior from Homs, Syria

Samir, a senior from Homs, Syria

Chad Adams, the principal of Roger C. Sullivan High School

Sarah Quintenz, the director of the Sullivan High School English language learner program

Matt Fasana, the assistant principal at Sullivan High School

Josh Zepeda, the English language learner social worker at Sullivan High School

Danny Rizk, a math and science teachers aide at Sullivan High School

REFUGEE HIGH

1

SEPTEMBER

Mariah

Mariah cant sleep. Tomorrow is her first day at Sullivan High School. Staring up at the underbelly of the top bunk occupied by her younger sister, Mariah considers the outfit shes picked out for her first day: white jeans, a blue and white shirt, and blue Converse sneakers with white trim and white laces. Shes also decided to wear her hijab again, this time with style. Mariah picked out a black scarf, which she plans to wrap into a turban. Shes anxious about starting at a new school. What will it be like? Will there be drama? Will life at Sullivan prove better than at the huge suburban high school where she barely survived her freshman year?

Sometimes when Mariah lies awake, she tries to revisit her memories from Basra, the coastal city in Iraq where she was born, but left at age ten. The fifteen-year-old doesnt recall much, but she likes to replay what she does. She remembers walking down the street with her eldest sister. Men would often approach her sister, something Mariah, whose arched eyebrows and barbed spirit have made her a favorite among high school boys, only understood once she got older. She remembers going to school and fearing traveling alone to the outdoor shower.

Soon, Mariah shifts back to her surroundings. The bedroom remains still. Its quieter now that Mariahs seventeen-year-old sister Farha moved to Atlanta to marry. But Mariah still shares the room with two of her sisters and their bedroom is rarely this peacefulMariahs arms are dotted with scars, all of them battle wounds from hair-pulling, shin-kicking fights. Before Farha left, Mariah was close with her older sister. That was before everything went sour last year. The thought saddens Mariah, but she isnt one to dwell. Farha is gone and Mariah gets a fresh start.

Chad Adams

Chad Adams sits at the edge of his bed. The heat, which he feels rising from the floor, suggests that summer lingers. But the sunless sky reveals the truth: fall waits just around the corner. Chad has always loved the first day of school. As principal of Roger C. Sullivan High School, Chad gets to hit reset every September. Its like New Years Eve, but better. And by his own logic, today marks Chads fifteenth shot at reinvention.

Planting his feet on the ground, Chad begins to visualize the day ahead of him. He imagines the school facade, marked by red bricks and white stone carved with modern gothic finishes. The building is large with two wings, each of which stretches out from the central lobby and covers nearly half a city block. The sign out front welcomes the students back and shines with the hope of a promising new year. Inside, the forty-one-year-old imagines himself in the auditorium welcoming new students and high-fiving those returning. Chad sees himself talking to parents, assuring them their kids are in good hands. He pokes his head into classrooms to check in on teachers. He jokes around with the security staff, who are stationed on every floor.

Visualizing the day helps Chad feel prepared. Without opening his blue eyes, he begins his mantrathe same one he practices each morning: I am calm. I am calm. I am calm. As he repeats the line in his head, he can feel his bodyshoulders, chest, stomachrelax. He lets the weight of his body sink into the mattress. He feels heavier with each repetition. Chad inhales through his nose and breathes out of his mouth. He repeats the mantra for a full minute. When he finishes, Chad turns his attention to his toes. He starts his third exercise of the morning. I am noticing my feet, he says to himself. He holds the thought for a few seconds before letting it dissipate. I am noticing my ankles. I am noticing my calves. My knees. Chad crawls his way to the tip of his head. When he acknowledges each part of his body, he opens his eyes. Chad begins every day like thishe has to.

Just after 6:30 a.m., Chad zigzags his way into the Rogers Park neighborhood. The rainy summer has turned the already verdant blocks surrounding Sullivan High School an even richer array of greens. In the remaining few blocks of his commute, Chad passes rows of blocky, heavily corniced two-flat apartment buildings and nineteenth-century Victorian homes. The neighborhood is marked by a smattering of murals that celebrate native lake fish and the popular local cartoon character Fly Boy. He passes signs, wet with dew, that read Hate Has No Home Here, and rainbow flags pinned to first-floor window frames. Few sounds travel across the neighborhood at this early hour. Only the elevated Red Line train drums a clicking bass line as it rolls to and from the Loyola and Morse Avenue stops. Soon, street traffic will start to pick up. The Ethiopian cafe, Royal Coffee, will open its doors at 7 a.m. and later the Cuban grocery store La Unica will welcome its first customers of the day. But for now, Chad lets the early-morning serenity sink in.

Wearing a slim black suit with his shaggy blond hair hanging at his shoulders, Chad punches his four-digit employee code into one of the schools heavy steel doors. The halls are quiet; only the custodians and the front desk clerk precede him here. On his way to school, Chad listened as President Trump threatened to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a program created by the Obama administration that gives immigrant youth brought to the United States unlawfully the temporary right to legally live, study, and work in America. Spanish is the second-most-spoken language at Sullivan, and Chad knows the school serves several Dreamers.

In the nine months since Donald Trump took office, hes been a source of fear at Sullivan. As soon as his term began, the Forty-Fifth, as Chad calls him, started a campaign to reduce the number of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers entering the United States. In January, he announced a travel ban barring citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the country. He pushed to allot $18 billion toward building a wall along the U.S.Mexico border and prioritized the prosecution of criminal immigrant violations such as illegal entry. Chad knows that such rhetoric could have a ripple effect and shake students living in already tenuous circumstances. And there are a lot of such kids at Sullivan. More than half the students, or over three hundred kids, came to the United States as immigrants or refugees.