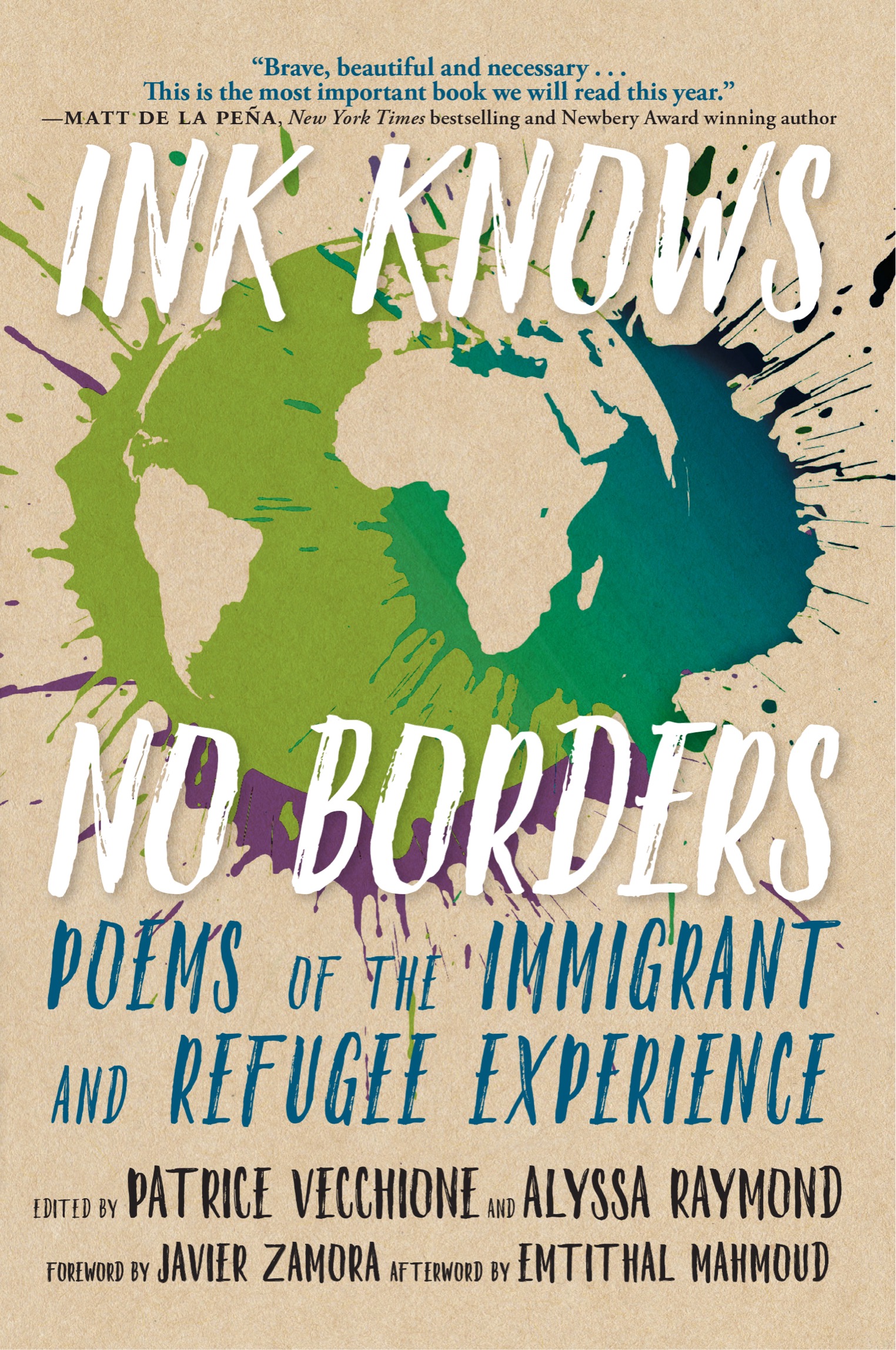

a triangle square book for young readers

published by seven stories press

Copyright 2019 by Patrice Vecchione and Alyssa Raymond

For permissions information see page 175.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors and high school and middle school teachers may order free

examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. To order,

visit www.sevenstories.com or send a fax on

school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Book design by Abigail Miller

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

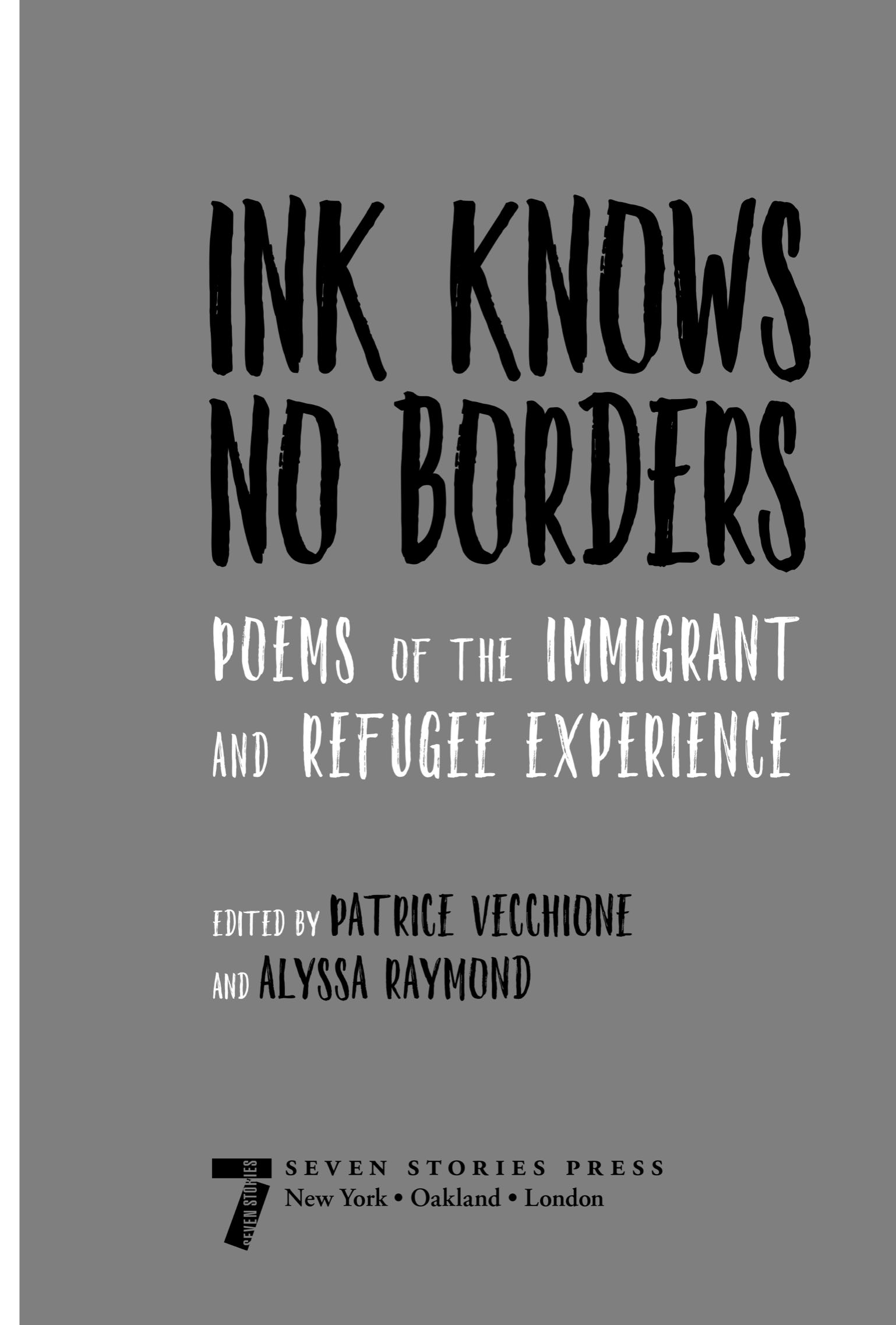

names: Vecchione, Patrice, editor. | Raymond, Alyssa, editor.

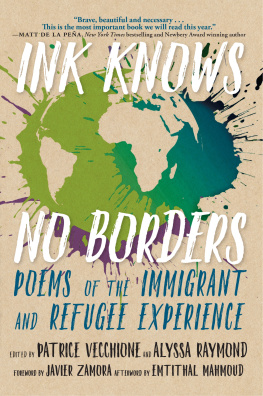

title: Ink knows no borders : poems of the immigrant and refugee experience / edited by Patrice Vecchione and Alyssa Raymond.

description: New York : Seven Stories Press, [2019] | Audience: Grades 7-8. | A Triangle Square Book for young readers. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

identifiers: LCCN 2018052736 (print) | LCCN 2018059209 (ebook) | ISBN 9781609809089 (Ebook) | ISBN 9781609809072 | ISBN 9781609809072 (paperback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781609809089 (ebook)

subjects: LCSH: ImmigrantsUnited StatesJuvenile poetry. | RefugeesUnited StatesJuvenile poetry. | American poetry21st century.

classification: LCC PS617 (ebook) | LCC PS617.I53 2019 (print) | DDC 811/.60803581dc 3

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018052736

Printed in the USA.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

To be rooted is perhaps the most important

and least recognized need of the human soul.

simone weil

I wish maps would be without

borders & that we belonged

to no one & to everyone

at once, what a world that

would be.

yesenia montilla

let me tell you what a poem brings...

it is a way to attain a life without boundaries.

juan felipe herrera

Editors Note

A t the time of this writing, with the manuscript of Ink Knows No Borders nearly complete, the United States is in a dismal mess. Children are separated from their families as they attempt to enter the country, young people who were brought to the US as children without documentation are threatened with deportation, and the Supreme Court has allowed the president to carry out his ban on immigrants based on the idea that some human beings are illegal.

In his poem Off-Island Chamorros, Craig Santos Perez writes this truth: Remember: / home is not simply a house, village, or island; home / is an archipelago of belonging. For people to leave their home and cross a harsh desert or sea, often with small children in tow, they must be fleeing something too difficult for many of us to fully imagine: civil war, political or religious persecution, gang violence, lack of work, hunger, or natural disaster.

Ink Knows No Borders celebrates the lives of immigrants, refugees, exiles, and their families, who have for generations brought their creative spirits, resilience and resourcefulness, determination and hard work, to make this land a home. They have come from the Philippines, Iran, Mexico, Russia, Vietnam, El Salvador, Sudan, Haiti, Syria, you name it. Enter the place of these poems, bordered only by the porousness of paper, and youll find the worlds people striving and thriving on American soil.

There is the daughter whose mother packed three days worth of underwear in a ziplock bag in case ICE showed up at her school, the child wishing to change her name to something more American, the dried desert creek where forty people sleep, the beer company that did not hire Blacks or Puerto Ricans, an immigrant mothers vindication when her math, much to the surprise of fellow shoppers, is proven correct at a check-out counter, a son who ached to be [as] beautiful as his praying Muslim father, the fifteen-year-old who understands her parents as poorly as they understand her, the young poet who writes, I dont know how to think of this / I wasnt taught to notice ones colors, and more, so much more.

These poets know that the pen holds a secret, a secret that can only be uncovered by putting that pen to paper, in a crowded coffee shop or some solitary place, maybe in the middle of night or when the dawn wont let you sleep, inspired, as you are, by birdsong or your own song. They know that This story is mine to tell. These lived stories, fire-bright and coal-hot acts of truth telling, are the poets birthrightand a human right.

Whether you were born in this country or another, whether you came here with the help of a coyote, crammed in a too-small boat, or with a visa and papers in order, whatever your skin color or first language may be, whomever you love, writing poems is a way to express your most authentic truths, the physical ache of despair, the mountaintop shout of your joy. Writing poetry will help you realize that you are stronger than you thought you were and that within your tenderness is your fortitude.

Not only does ink know no borders; neither does the heart.

patrice vecchione and alyssa raymond

Foreword

america, am I not your refugee?

fatimah asghar

W hen & how can you start to tell the story of where you or your family comes from? The why of being in another country? And should you? Growing up in San Rafael, California, after emigrating from El Salvador unaccompanied at the age of nine, I never asked these questions. Didnt dare. From the moment I crossed the border through the Sonoran Desertno, way before thatfrom the morning I said goodbye to Grandpa from the back of a bus near the GuatemalaMexico border, I knew never to speak of what would happen.

I would not see Grandpa for six years, Grandma for nineteen. When I was reunited with my parents, they told me not to tell anyone about being born in another country, about my illegal entry, about what I had experienced those two months when no one knew my whereabouts, when even the people in my parents ESL class prayed and lit candles so I would make it here safely. It became my secret. In her poem Return, Gala Mukomolova writes, It happens, teachers said, that a child between countries will refuse to speak. Absolutely. Since our reunion in Arizona, Ive spoken to my parents about those two months only twice in my life. Both times, after I started writing poetry. Both times, their guilt, their remorse, their asking for forgiveness, made us stop with the questions, and we let out our tears.

Before I had the tools (the pen and paper of poetry) to replay, analyze, revise the trauma my refugee story embodied, I held all of that anger deep inside, believing that what I had been through could be forgotten, but trauma doesnt work that way. I thought no onenot my parents, not my friends, not the best counselorcould understand what I had experienced. I truly believed I had been the only nine-year-old who had migrated by himself, crossed an ocean, three countries, and a desert. Like Mahtem Shiferraw describes in her poem Talks about Race, I [didnt] know how to fit, adjust myself within new boundaries / nomads like me have no place as home, no way of belonging. I started drinking and hanging out with the wrong people in my apartment complex. Wearing certain gang colors. My friends and I were not real gangsters; we were just trying to prove ourselves to one another. I couldve been an honor-roll student in middle school, but my behavior kept me from it. Once, I threw a bottle of water at my seventh-grade teacher. I was kicked out of class multiple times for saying something vulgar to make everyone laugh. I needed to be seen. Heard. I wanted someone to ask me what was wrong with me and truly mean it. For me to be able to break down and cry in front of them. That never happened.