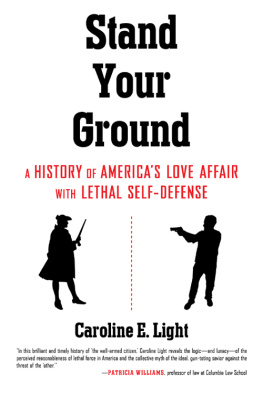

For Sandy Light,

Armed with common sense and compassion

AUTHORS NOTE

M OM THE S HARPSHOOTER

I have vivid memories of accompanying my parents on trips to a shooting range in southwestern Virginia. They shot skeet, in which a small, saucer-shaped clay pigeon was launched from a machine across the sky, in front of the shooter, and the more challenging trap, where the target flew up and away from the shooter. Id interrupt my play in the field behind the range when I heard my mother shout Pull! and would look up. The clay pigeon would soar across the sky, then shatter into tiny bits as the pellets from Moms gun tore through it. She was an excellent shot, particularly for someone with scant time to spend on target practice. She had three children, me and two younger siblings, and back in the early 1980s, shooting facilities and gun clubs didnt provide childcare, as some do now.

Both of my parents shot for recreation. My dad, who had become familiar with guns through his service in the navy, occasionally went on hunting expeditions with friends from work, bringing back an assortment of small dead animals. At dinner after one such excursion, I recall chewing on a less-than-delectable piece of roasted quail, trying not to think about the lovely and harmless creature it had come from and pausing to spit out pieces of birdshot. Despite the occasional family dinner featuring the kill of the day, guns and hunting constituted a peripheral part of my life.

I grew up white and middle-class in the suburban South, which is to say that I grew up with a measure of security in both my social position and my sense of distance from physical danger. As a historian who studies the ways in which collectively shared memoriesthe histories that take shape as truth in the public imaginationinfluence national belonging, I look back on memories like these for a sense of what I dont remember. Specifically, I seek out gaps in my recollection that highlight crucial departures from todays sense of urgency around home and personal security. My early trips to the shooting range felt mundane, even boring, comparable to watching my parents play tennis. But unlike tennis rackets, guns werent kept in our home. My parents werent interested in armed self-defense.

In contrast to my memories of my parents trips to the gun range, todays widespread reverence for what I call do-it-yourself (DIY)-security citizenship brings to mind a different world. DIY-security citizenship is based on a set of ideologies, rooted in heroic histories, that see lethal self-defense as a core responsibility of the ideal citizen who stands his ground in the face of perceived threat rather than retreating from a fight. This contemporary ideal emerged in response to a growing sense of insecurity, a belief that we must be prepared to kill or be killed, to shoot first and ask questions later. It rests on an urgent need to defend oneself from a litany of threatening figures, including (but not limited to) terrorists, undocumented immigrants, and criminal strangers. In fact, the DIY security citizen has appeared primarily in opposition to these perceived threats, and leaves no room for ambiguity between heroic good guys and dangerous bad guys.

In spite of the invocation of heroism and independence, the DIY-security ethos has a destructive downside. For one, it rests on the fallacy of urgent insecurity. In spite of falling crime rates, more people are acquiring guns for personal and home protection than ever before. When I was growing up, most gun owners were hunters; now, most own guns for personal protection.

Our nation boasts the highest per capita rate of gun deaths and deaths by mass shooting, defined as an episode in which four or more people are killed or wounded. In 2015 alone there were 372 mass shootings, resulting in 475 deaths. The proliferation of shootings, particularly in our schools, amplifies a national sense of vulnerability, so that citizens who see themselves as law-abiding nevertheless feel the need to take matters into their own hands.

But DIY-security citizenship is not just about gun ownership. Guns and their proliferation in the United States are only the tip of the iceberg of a much larger and more widespread belief system that frames lethal self-defense as a core ideal of good citizenship. This principle places idealized, law-abiding citizensnot all citizensin the service of lethal self-defense and equates good citizenship with the capacity to stand ones ground against criminal strangers. According to the National Rifle Association, a good citizen is an armed citizen. In fact, the NRA has gone so far as to register the phrase armed citizen and build a political advertising campaign around it. For the NRA, an Armed Citizen is the quintessential emblem of patriotism. This ideal suggests that we must all be prepared to defend ourselves; however, our contemporary call to arms is based on unspoken but powerful assumptions that exclude many from the protective and exonerating rhetoric of law-abiding citizenship.

Appeals to individual DIY security as the solution to our nations most urgent anxieties criminalizes many who do not fit the terms of idealized citizenship, particularly people of color, gender-nonconforming people, and the poor. Moreover, women of all races, classes, and ethnicities often find themselves criminalized if they try to stand their ground against violent male partners. When contemporary advocates of lethal self-defense entreat law-abiding citizens to take up arms against criminal strangers, they participate in a prolonged tradition of excluding and criminalizing the real victims of violence, the groups historically most in need of protection.

This appeal to DIY-security citizenship is in many ways nothing new. The heroic figure of the Armed Citizen has its roots in a long history in which the privilege of violence, often justified as self-defense, has rested in the hands of the powerful few. While our legal terrain has shifted to extend the rights, privileges, and protections of citizenship to women and to people of color, the advantage of self-defensive violence continues to empower propertied white men. Ultimately, todays vocal call to arms rests on historic fallacies of reverse victimization, where those excluded from the full benefits of citizenship became the criminalized strangers against whom the Armed Citizen takes defensive action. In spite of its democratic appeals to all law-abiding citizens, DIY-security citizenship only welcomes some, to the exclusionand endangermentof the many.

The material traces of these histories are all around us, but we often dont notice them unless we are subject to their exclusions. Growing up white and middle-class in the South meant that I inherited a complicated but widely celebrated heritage, one concretized in memorials that dotted the Southern landscape. A certain comforting worldview was reflected in the built environment. I grew up blithely unthreatened by historical symbols of domination, like the Confederate flag emblazoned on the backs of pick-up trucks and in store windows. To a white girl born in Virginia, these everyday sights appeared like natural, commonsense reminders of a glorious past. Almost through osmosis, I learned to see the flags presence as a benign symbol of a proud legacy, a politically neutral reminder of a true history. Given its reliable and almost ubiquitous presence, I failed, until adulthood and advanced education intervened, to develop a critical awareness of the larger significance of this and other emblems of white supremacy, ones that have shaped the way we understand history itself.