Table of Contents

Introduction

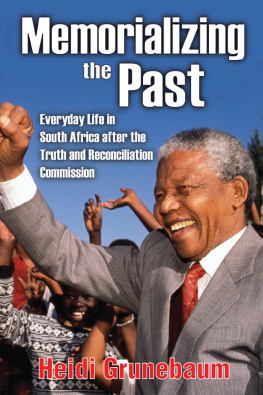

When black South Africans by the millions turned out to vote for the first time in their lives in April 1994, the world saw them standing patiently from before dawn, in lines so long they often seemed endless. Even those who could not read, and that, arguably, was the vast majority, knew they were in the process of making their own miracle. The occasion was so awesome that when reporters like me asked the young, the old, the women and the men how they felt, one after another uttered the same response: Im so happy.

But beneath the patience and the pride lay the pain of indeterminate layers, the result of years of enduring a system so brutal that it has few parallels in modern history. The apartheid regime had kept the majority of its peopleblack and Indian and coloredseparate, unequal. When they protested, they were often tortured. Death was frequently so gruesome as to defy even the most active imagination. And for a variety of reasons, those who suffered at the hands of the apartheid state usually suffered in silence.

The South Africans who negotiated the torturous route toward the 1994 elections knew that if the country was to sustain its peaceful transition to democracy, the victims voices had to be heard. Some balm would be needed to dress, if not heal, their wounds. All South Africans would have to learn as much as possible about the causes, nature, and extent of the human-rights violations under apartheid. In order to forge a future, the nation would have to honestly and squarely confront its past. For these reasons, the final clauses of South Africas interim constitution read as follows:

The adoption of this Constitution lays the secure foundation for the people of South Africa to transcend the divisions and strife of the past, which generated gross violations of human rights, the transgression of humanitarian principles in violent conflicts and a legacy of hatred, fear, guilt and revenge. These can now be addressed on the basis that there is a need for understanding but not for vengeance, a need for reparation but not for retaliation, a need for ubuntu [the African philosophy of humanism] but not for victimization.

In order to advance such reconciliation and reconstruction, amnesty shall be granted in respect of acts, omissions and offences associated with political objectives and committed in the course of the conflicts of the past. To this end, Parliament under this Constitution shall adopt a law determining a firm cut-off date which shall be a date after 8 October 1990 and before 6 December 1993 and providing for mechanisms, criteria and procedures, including tribunals, if any, through which such amnesty shall be dealt with at any time after the law has been passed.

Subsequently, the first independent body established in the post-apartheid era was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Created by an Act of Parliament known as the National Unity and Reconciliation Act, the TRC, as it came to be known, was designed to help facilitate a truth recovery process. It was unique in the history of such commissions around the world in that it called for testimony before it to be held in public.

Controversy dogged the TRC from the start. There were those who believed that the perpetrators of gross human-rights violations should appear before a court of law, as Nazi war criminals were forced to do at Nuremberg; that, they insisted, was the only possible path to justice. But there were also those who pointed out that it was not a battlefield victory that had produced the end of apartheid, but a settlement negotiated by victims and perpetrators alike; amnesty, they argued, had been a necessary precondition for securing the cooperation of the previous government and its security forces. The deal was to hold out the promise of amnesty in exchange for the full truth about the past.

With strong support from President Nelson Mandela, the TRC began operating in December 1995, with Nobel Prize laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu as its chairman. Nongovernmental organizations compiled a list of possible members for President Mandela; the president, in turn, added some names and made the final selection. Archbishop Tutus sixteen commissioners included ministers, doctors, lawyers and others from civil society. Their mission: to produce a report to Parliament and President Mandela that would paint the most complete picture of the abuses that occurred between March 1, 1960, and May 10, 1994.

The TRC was armed with subpoena powers and staffed with sixty investigators. It would hold hearings that would give victims an opportunity to tell the world their stories of pain, suffering and loss. And it would question victimizers about how and why they had caused that pain, suffering, and loss, with a particular emphasis on just how widespread the human-rights abuses had been and to what extent they had been sanctioned by the apartheid government. Gross violations of human rights were defined as murder, attempted murder, abduction, and torture or severe ill treatment.

The commission was organized into three committees: Human Rights Violations, Reparations and Rehabilitation and Amnesty. All told, commissioners took more than 20,000 statements from survivors and families of political violence. They held more than fifty public hearings, all around the country, over 244 days. The Amnesty Committee, by law independent of the others (its rulings could not be appealed or overruled, except by the countrys highest court), received approximately 7,050 amnesty applicationsfully 77 percent of them from prisoners. All three committees were plagued by a huge workload and inadequate resources. And even Archbishop Tutus most eloquent pleas could not persuade whites to come forward to testify in significant numbers. Near the end of the process, one poll suggested that the Truth Commission had done more to hurt race relations than to promote reconciliation. Indeed, the commission itself had to confront internal allegations of racism.

But most agree that the reality is much more complex. Many Afrikaners who charge that the commission was biased against them from the start, for example, also acknowledge that they learned for the first time the full extent of state-sponsored crime from testimony before the Truth Commission. And while some victims and survivors of the apartheid government say their agony wont end so long as perpetrators get amnesty and victims get next to nothing (reparation, for those who qualify, comes to less than $200 per victim), others say that learning how and where their loved ones met their end has provided a certain closure, a measure of peace.

As of this writing, the Truth Commissions report is expected by the end of October; the TRC will then be suspended, to be reconvened once the amnesty process is completed in 1999. At that time, the commission likely will approve the Amnesty Committees full report and determine whether it necessitates changing the final report in any way.

The commission hopes its report will provide the history lesson needed to ensure that South Africas tragic past never repeats itself. The proof of the lesson may not be clear until future generations have had a chance to consider the findings with the grace of time and distance. But one of its certain legacies is the voices, so long unheard, that now speak for the record about a particularly brutal history. Those who testified, those who heard them and those, like Antjie Krog, who report on what they said, are all living South Africans who are struggling to make individual and collective sense of the past and to push ahead into a future that may or may not fulfill the promise felt by those first-time voters in 1994. The Truth Commission, no more perfect than the messy work-in-progress called democracy, allowed them to face together, for the first time, the profound task ahead.

Next page