THE ROAD BEFORE ME WEEPS

Copyright 2019 Nick Thorpe

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018962173

ISBN 978-0-300-24122-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is for Mbaye

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the hundreds of men, women and children who shared their stories with me during some of the most difficult moments of their lives. Many of their names appear in the text, others preferred to remain anonymous. The courage of those who set out into the unknown is matched only by the courage of those who stay at home, come what may. This book is dedicated to Mbaye, wherever he may be, who rescued my sister and I when we were lost and afraid, long ago, on our first night in Dakar.

I want also to thank the many volunteers, aid workers, translators, government officials, police and border guards who gave information, permissions, tea or advice in many countries. In particular, staff of the United Nations refugee agency, the International Organisation for Migration, Mdecins Sans Frontires, the Hungarian and Bulgarian Helsinki Committees, Frontex and numerous volunteer groups and activists were generous with their time and help.

My work for the BBC gave me the opportunity to spend many months along the borders of the Balkans. My thanks to commissioning editors and colleagues too numerous to mention for their interest in the story and their companionship.

In Budapest Blint Ablonczy, Suzanna Zsohr and Michael Ignatieff, and in London Xandra Bingley and the anonymous readers at Yale, read early drafts of the book and offered valuable suggestions. Gerald Knaus magnanimously shared with me his recollections of the gestation and birth of the EUTurkey deal.

Huge thanks are due to my Hungarian publishers, Scolar Kiad, and in particular Nndor rsek and Andrea Ills for encouraging me to write the book in the first place. At Yale University Press, Robert Baldock, Rachael Lonsdale, Julian Loose, Marika Lysandrou, Clarissa Sutherland and many others worked assiduously to produce this beautiful edition. Finally, I would like to thank my wife Andrea and my sons Jack, Caspar, Daniel, Matthew and Sam, my mother Janet, my sister Mish and my brother Dom, for tolerating my long absences, and for all their love and support.

ILLUSTRATIONS

All photos taken by the author.

INTRODUCTION

THE FACES AT THE FENCE

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to the ports and coasts for transportation...

William Shakespeare, The Book of Sir Thomas More

On a world scale emigration has become the principal means of survival.

John Berger

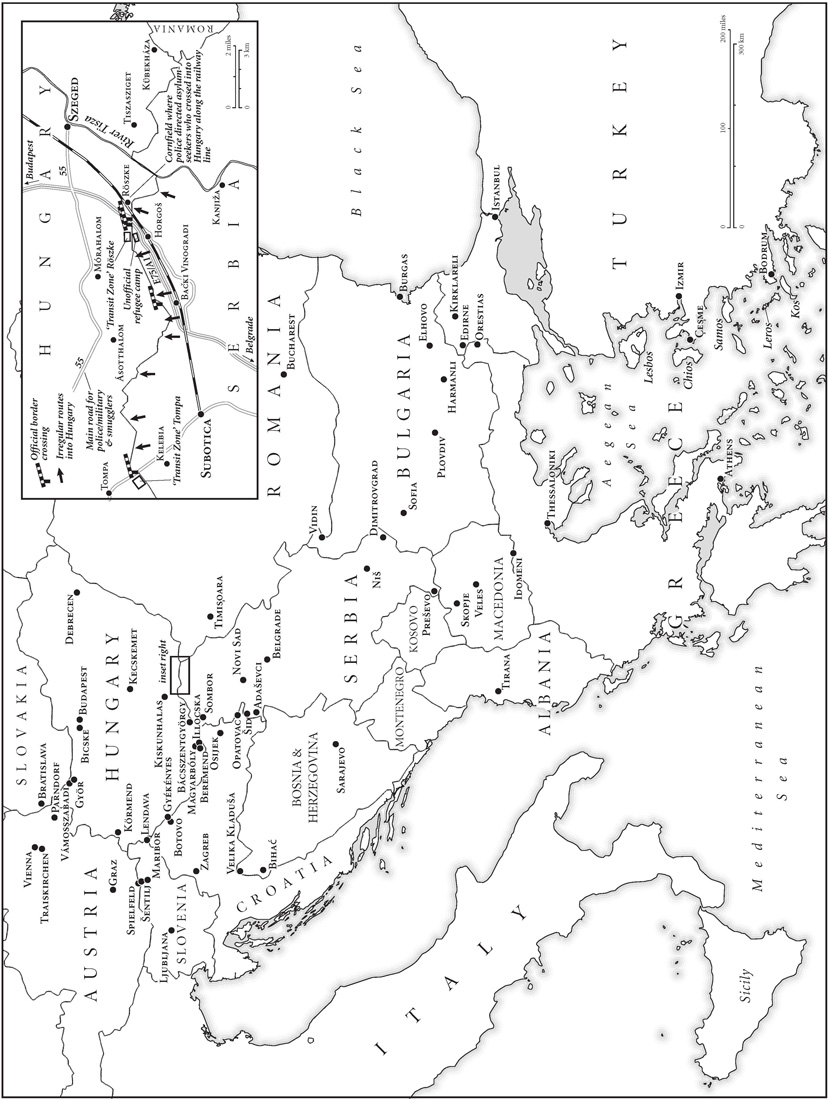

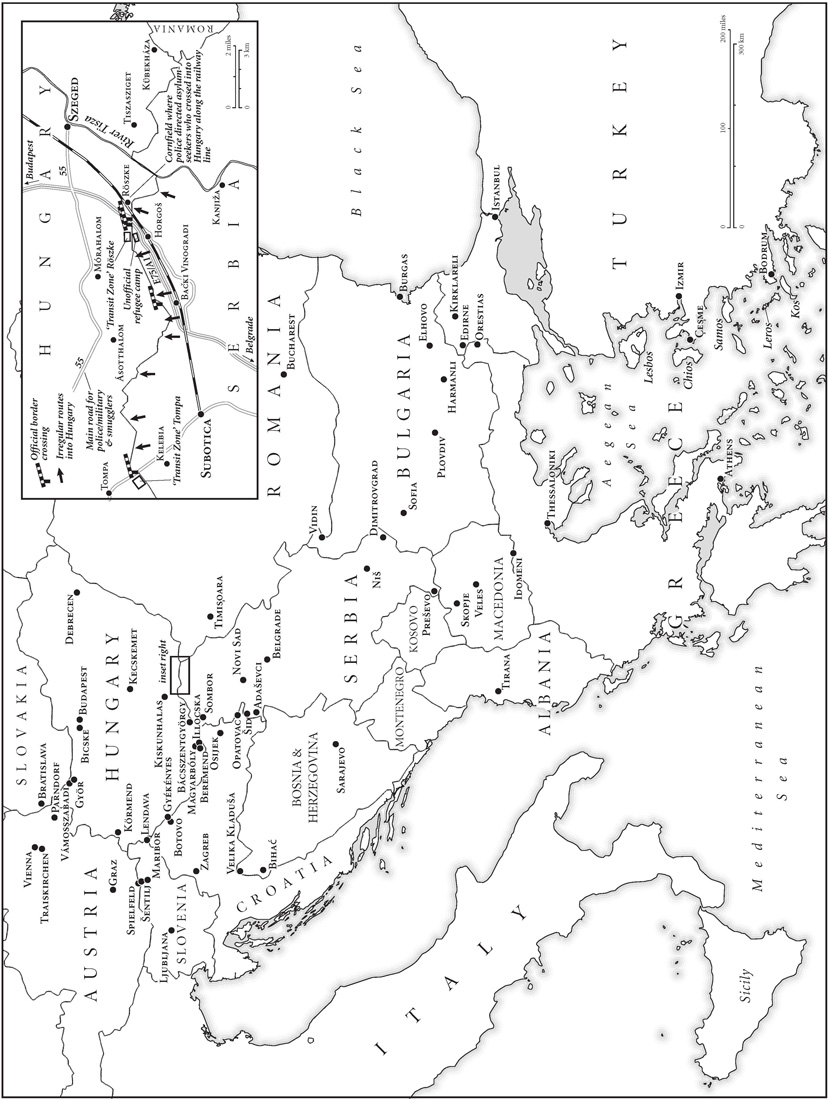

This is a book about refugees and migrants along what became known as the western Balkan route, from Turkey to Western Europe, from 2014 to 2018. This is just one of the five main routes into Europe, but in 2015 and the start of 2016, it was the most trodden.

Migration is like a balloon, an official of Frontex, the European border control agency told me, you squeeze it in one place, it grows bigger somewhere else. The deals done in distant capitals, the walls and fences built, and the detection equipment installed have had a certain deterrent and delaying effect. But those who are determined enough will always find a way through. All the means taken to stop them simply increase their suffering, the cost of the journey and their dependence on the criminal underworld which facilitates their movement.

Much changed in the world while I was writing this book. What began as a chronicle of a mass influx turned gradually into detective work, tracing individuals from the mid-point to the end-point of their journeys. Such is the fragility of their status, some of the characters may be in other countries by the time you read these words. Some may have struggled gladly or reluctantly home.

It is my hope that this book, as a chronicle of an age-old phenomenon during a certain short period in modern European history, will remain a useful reference for readers many years from now. The book raises questions of human freedom and hospitality, of rights and obligations which are of crucial importance in any age.

From my home in Budapest, I returned over a four-year period to the same tracks across fields and forests, and to the same villages and towns where people rested on their journeys or were temporarily incarcerated. When the fence on the Hungarian-Serbian border was completed in September 2015, I traced the flow of people through Croatia and Slovenia. When the trickle of people over and through the Hungarian fence fell almost to zero, in the autumn of 2017, I traced people across Romania into Hungary, through Slovakia and the Czech Republic into Germany. Others took the route through Albania or Bosnia, into Croatia, Slovenia and Italy. Since their arrival in Western Europe, I have continued to follow the fate of several dozen people. Some of their stories conclude this book.

This is also the story of the help and hostility they met on their way, and when they arrived. My adopted homeland of Hungary produced the fiercest political opposition, in the form of Viktor Orbns Fidesz government, to both refugees and migrants. My familiarity with the Hungarian prime minister I have known him since 1988 gave me a useful perspective from which to follow the refugee phenomenon across Europe and the world. Though I write in the shadow of his fence, my privileged status as a BBC correspondent gave me the opportunity to zig-zag through it at will, and to speak to whomsoever I wished.

I place the experiences of those along the route in the wider context of European and global migration, and the growing fear of terrorism. And in conversations at the end of the book, with some of those who are now accepted in Germany, France and Switzerland, I explore the successes and setbacks of integration.

The title, The Road Before Me Weeps, was first suggested to me by my friend Balzs Dong Szokolay, a brilliant Hungarian musician and master of all manner of flutes, saxophones, bagpipes and other wind instruments. It There are several versions of the text. In the best-known, a man walks down the village street, so sad that even the road weeps before him, to visit the girl he loves, who has forsaken him for another man. No door opens to him.

In 1987, the Hungarian film-maker Sndor Sra gave the same title to a series of four films about the plight of the Szeklers of Bukovina, forced from their villages as refugees during the Second World War, never to return.

While I was writing, the people of Britain voted to leave the European Union (EU) and Donald Trump was elected forty-fifth president of the United States. Both outcomes were strongly influenced by the desire of the electorate to regain control of their countries from those portrayed as political and business elites who favour globalisation. Both the champions of Brexit and Donald Trumps campaign leaned heavily on public concern about immigration. It is ironic that while East European governments opposed migrants from outside Europe, many people in Britain were swayed to leave the EU because they resented the influx of East Europeans to their own countries. New business elites came to power in many countries, and stayed in power in others, because they were better able to speak the language of the people.

Next page