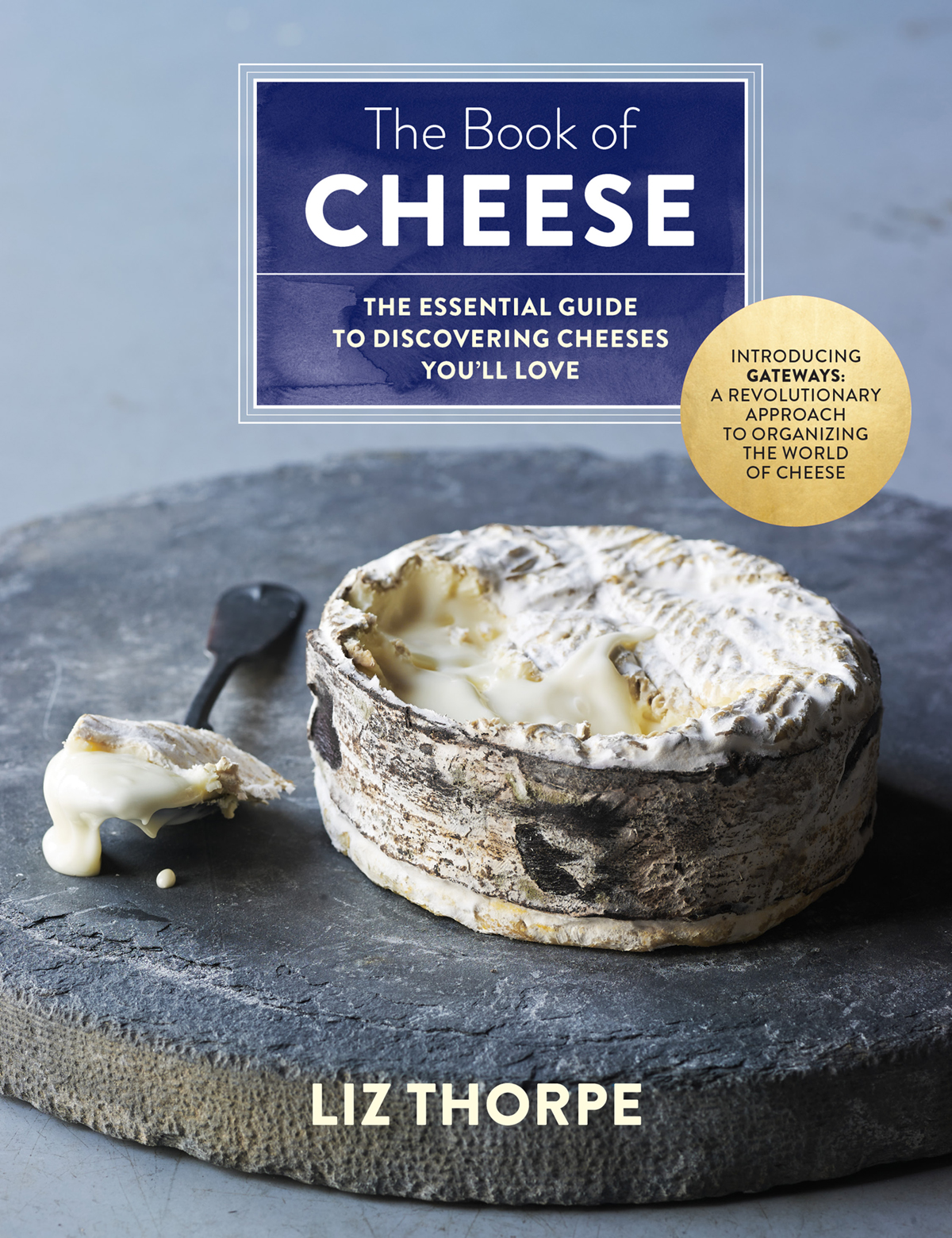

I walked into a small Brooklyn butcher shop one afternoon in 2000, having recently been laid off from my dot-com job, and found myself lulled by the siren call of a cheese case. The meat guys stood behind the counter while I ogled what seemed like an impossible number of cheeses. There were maybe twenty, of which I was familiar with four or five. Those in the counter crew were veritably bouncing on their tiptoes, asking politely, if somewhat urgently, what they could get for me. They wanted to sell me something, but I just wanted to sample all those cheeses. After that, I wanted an explanation for how so many existed in the first place. I remember one with a murky black line through the center, like a teachers pen slash. Several reminded me of rock slabs, their bases littered with little crumbs and flecks. A few oozed silently. I dont recall exactly when I went from staring at them to buying and eating them, but I remember feeling intensely curious as to where they came from, and also mildly shocked that a food I had known my whole lifecheesewas actually hundreds of different foods.

Being the consummate good student with an unexpected amount of free time, I took the only step I could think of. I bought a book about cheese. It was a revelation, a guide called Cheese Primer, written by a man named Steven Jenkins. I recall diving into this book, organized by country, and expecting to master French cheese. And then the bizarre sensation of looking down at the book and seeing Id turned many pages but hadnt retained anything. The cheeses all slipped past me, a parade of names in a language I didnt speak and a slew of facts that quickly jumbled in my (usually stellar) memory. It was all so abstract. I wanted to know these cheeses, to understand them in reference to one another. I wanted to walk into that butcher shop, point to a cheese, and confidently say, Id like that one (while knowing that I really would like it). After several cover-to-cover reads of Cheese Primer, I concluded that I was more literal than I realized, and my only recourse should I wish to understand cheese was to go find Mr. Jenkins and get him to hire me. Together, we could taste and travel and maybe then Id master the world of cheese.

Luckily, Jenkins was the cheese guru of Harlems Fairway Market, and he not only took my call but offered to meet me in his store. Happily, he confirmed that my literalism was the best way to learn cheese. He suggested that I take a job at the Fairway counter, where I would cut, wrap, and sell cheese all day. His counter, by the way, probably had 300 cheeses. Talking cheese while scrambling back and forth behind forty linear feet of it would, he assured me, make it stick in my brain. Unhappily, he did not offer me a travel pass to Europe or an assistantship doing rarefied things like research and blind cheese-tasting. And there were no women working at his counter. Heck, there was no one under forty-five at his counter. The pay was, I think, minimum wage. And, to tell the truth, I was just plain scared. My fledgling cheese curiosity was threatening to tank my boring, predictable, post-collegiate life. I thanked Steve, declined the job, and vowed to keep cheese as my weekend hobby.

But I still thought about it. Id graduated from reading about cheese to reading about cheese while tasting it. Id buy small wedges of a few things and write down what they reminded me of. Then Id bone up on the facts. What I began to notice was that my tasting notes were all about my memories. I had no idea what the soft, silken cheese Reblochon was supposed to taste like. But it felt like my moms scrambled eggs (she still makes them better than anyone), slightly wobbly, knitted together with a tongue-coating skim of butter. Unwrapping a triangular wedge of Reblochon, and again after swallowing some, I could close my eyes and feel myself next to D.W., the chestnut quarter horse I rode in middle school. I could smell what for me had been the soothing intoxication of equine perspiration, fresh hay, leather saddles, andhanging in the backgroundmanure. I was dimly aware that telling my friends that a cheese tasted like poop wasnt going to make them try it, but I could tell them that eating a bite transported me to a place where I had been supremely happy.

My efforts to keep cheese a weekend hobby were steadily failing. I spent my days at a job that I didnt particularly care about and pondered how adults spent their entire lives at work when they kind of hated their work. The cubicle was killing me. I wondered if I could invent a career out of cheese. So I started looking around again, and my cold calling brought me to the New York City institution Murrays Cheese. Once again, I was given the advice that Id have to work the counter if I really wanted to learn the cheese. This time I was ready, and I said yes. I gave myself a year to see if cheese and I could really be something and got behind the counter a few weeks later. At first, working the cheese counter was terrifying. I lived in low-grade panic that a customer would ask for something that Id never heard of (a likely scenario as I hadnt heard of much), and when they inevitably did, I scrambled to fill time while I scanned 200 cheeses looking for the handwritten sign that most closely approximated what I thought theyd said. To appear conversational, I asked what they liked about that cheese. Usually, they told me how it reminded them of another cheese but it was better. Happily, that other cheese was often one I knew. Cheddar, say. Or maybe Brie.

As the months passed and I began to master Murrays offerings, I was able to use this trick with the customers who walked in and didnt know what they wanted. Id start by asking them what basic cheeses they did or did not enjoy. Knowing that they liked Blue told me they were open to stronger flavors; they werent afraid of salt; they were likely to be more adventurous. Hearing that Havarti with dill was one of their favorites told me they preferred more approachable flavor; that a cheese with a moldy rind might turn them off; that rich, fatty cheese would make them happy. It gave me a jumping-off point. Within a few months, I stopped asking if they wanted an English cheese or an Italian cheese because most people had no idea what that might entail. And, over the years as the cheese choices multiplied exponentially, being English wasnt likely to entail much at all. Suddenly, the English were making every style of cheese imaginable.