Copyright 2016 by Adrian Tinniswood

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, contact Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tinniswood, Adrian.

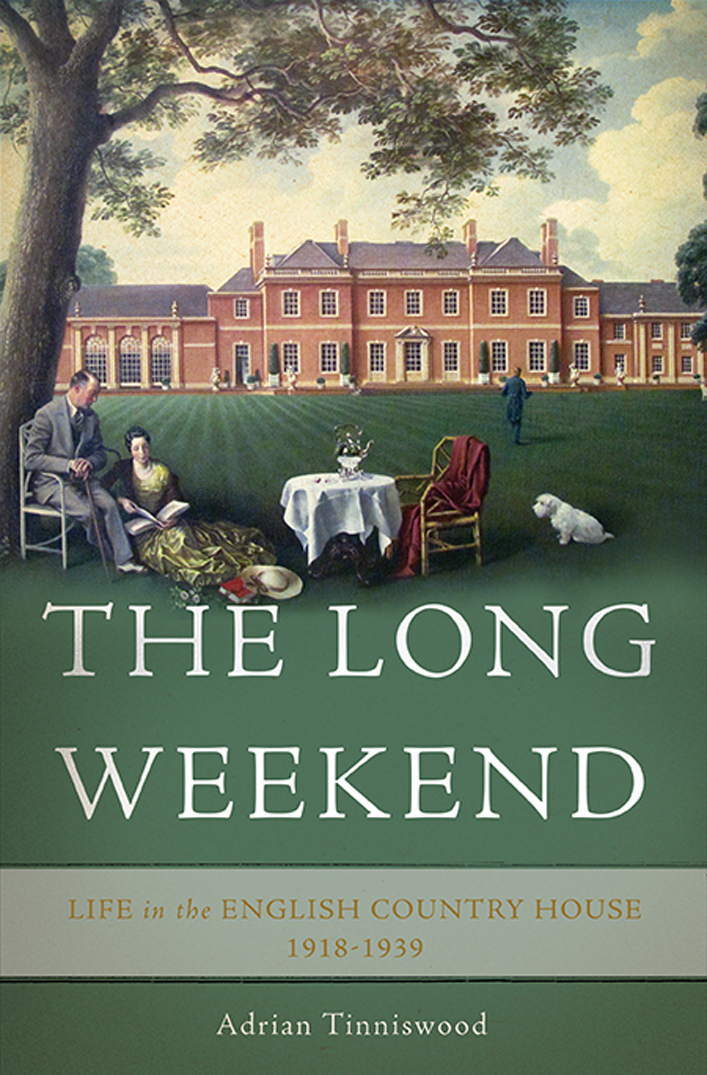

Title: The long weekend: life in the English country house, 1918-1939 / Adrian Tinniswood.

Description: New York: Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015049302 (print) | LCCN 2015049573 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465098651 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: England--Social life and customs--20th century. | Country homes--England--History--20th century. | Mansions--England--History--20th century. | Country life--England--History--20th century. | Aristocracy (Social class)--England--History--20th century. | Aristocracy (Social class)--England--Biography. | Landowners--England--History--20th century. | Social change--England--History--20th century. | England--Social conditions--20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain. | HISTORY / Modern / 20th Century. | HISTORY / Military / World War I. | HISTORY / Military / World War II.

Classification: LCC DA566.4 .T56 2016 (print) | LCC DA566.4 (ebook) | DDC 305.5/2094209042--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015049302

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my friend

Godfrey Napthine

19542015

People who formerly lived in very large houses are now getting out of them. As to who goes in is another matter.

COUNTRY LIFE (OCTOBER 25, 1919)

Its rather sad, she said one day, to belong, as we do, to a lost generation. Im sure in history the two wars will count as one war and that we shall be squashed out of it altogether, and people will forget that we ever existed. We might just as well never have lived at all, I do think its a shame.

NANCY MITFORD, THE PURSUIT OF LOVE (1945)

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

THERE IS NOTHING QUITE AS beautiful as an English country house in summer.

And there has never been a summer quite like that Indian summer between the two world wars, a period of gentle decline in which the sun set slowly on the British Empire and the shadows lengthened on the lawns of a thousand stately homes across the nation.

At least, that is the conventional view of a period that has always been seen as witnessing the end of the country house. One by one, so the story goes, the stately homes of England were deserted and dismantled and demolished, their estates broken up, their oaks felled, and their parks given over to suburban sprawl.

Theres certainly truth in that. But it masks an alternative narrative that exists side by side with the familiar tale of woe. A narrative that saw new families buying, borrowing, and sometimes building themselves a country house, which introduced new aesthetics, new social structures, new meanings to an old tradition. A narrative, in fact, that saw new life in the country house. That is what The Long Weekend is all about.

I n 1931 John Galsworthy, the gentle chronicler of a passing age, captured the essence of a certain type of interwar house party, in all its lovely, lazy, languorous tedium. One day is very like another, he wrote:

The men put on the same kind of variegated tie and the same plus fours, eat the same breakfast, tap the same barometer, smoke the same pipes and kill the same birds. The dogs wag the same tails, lurk in the same unexpected spots, utter the same agonised yelps, and chase the same pigeons on the same lawns. The ladies have the same breakfast in bed or not, put the same salts in the same bath, straggle in the same garden, say of the same friends with the same spice of animosity, Im frightfully fond of them, of course; pore over the same rock borders with the same passion for Portulaca [moss roses]; play the same croquet or tennis with the same squeaks; write the same letters to contradict the same rumours, or match the same antiques.

Perfect. Yet in defining the house party, in pinning down the sameness, Galsworthy allowed something of its infinite variety to escape. Country-house parties were not all the same.

Some were small, intimate affairs involving half a dozen old friends. Others were big and formal and packed with dignitaries. In November 1934, for example, the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire entertained twenty guests at Chatsworth for one of their grandest parties. Guests of honor were the Princess Royal and the Earl of Harewood, who hadnt visited since 1921 when the earl, then Viscount Lascelles, proposed to his princess. Shooting parties were laid on for the Saturday and the Monday, and the Devonshires invited a glittering gaggle of acquaintances for the weekend to meet the royal couple, including the Duke and Duchess of Portland from Welbeck Abbey, the Marquess and Marchioness of Londonderry, art historian Kenneth Clark, and Conservative politician Lord Hugh Cecil.

Some house parties lasted no more than forty-eight hours. Others went on for an awfully long time: in Scotland, a long train ride from London, an invitation to shoot often meant a visit of three weeks. Besides meeting royalty and shooting, many parties were convened for a particular purpose. In January 1935, Chips Channon and his wife drove up to Lincolnshire to stay with Lord Brownlow, better known as Peregrine Cust, the courtier who the following year would take Wallis Simpson to France while her lover renounced his throne. Fellow guests at Brownlows seventeenth-century Belton House were Duff and Diana Cooper, Viscount and Viscountess Weymouth, and Lieutenant-Colonel the Hon. Piers Legh and his American wife. Channon was a little overwhelmed by Belton; it was almost overful of treasures, he thought. And his fellow guests were frankly bores.) The real purpose of the gathering lay elsewhere. After dinner, the party set out in cars for an invitation ball the Duke and Duchess of Rutland were holding for their two teenage daughters at Belvoir Castle, ten miles away.

Channon was altogether more impressed with Belvoir. The ducal daughters both looked beautiful; colored lights in the trees lit the way up to the house; and the ball, with music by Emilio Colombo and his orchestra, was a glorious Disraelian festival, and the castle illuminations could be seen for miles. Violet, the seventy-eight-year-old dowager duchess of Rutland (and mother of Diana Cooper), cut a particularly imposing figure in white, surrounded by her descendants, thirty of them, including a gaggle of small grandsons in black suits.