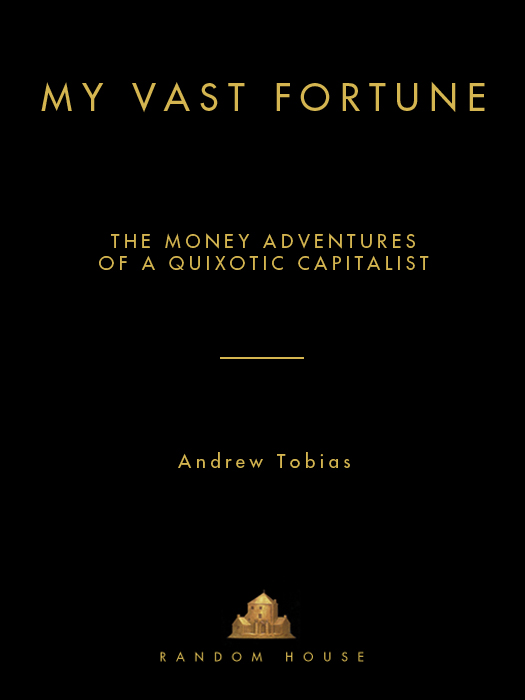

Copyright 1997 by Andrew Tobias

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Caution: Portions of this book have been published in other forms elsewhere. You are purchasing words that may have been previously read.

Portions of this work were originally published in Worth magazine and Getting By on $100,000 a Year by Andrew Tobias (Simon & Schuster).

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Harcourt Brace & Company for permission to reprint excerpts from The Only Investment Guide Youll Ever Need by Andrew Tobias. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace & Company.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tobias, Andrew P.

My vast fortune : the money adventures of a Quixotic capitalist/

Andrew Tobias.1st ed.

p.cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79984-5

1. Tobias, Andrew P. 2. Capitalists and financiersUnited States

Biography. I. Title.

HC102.5.T63A3 1997

332 .092dc21 97-15315

Random House website address: http://www.randomhouse.com

v3.1

Disclaimer: Any phrase, passage or construction herein that may strike you as funny should not be taken as such. Do not be fooled. This is serious business. Thinly cloaked as an appeal to amusement and greed, the real aim of this book is to make kneejerk liberals (of whom the author basically is one) a little less automatically reflexive; and conservatives (of whom the author claims several as friends) a touch more compassionate. As that old wordsmith George Bush might have phrased it: Bleeding heartsgood. Jerking kneesbaaaad.

You cant have everything. Where would you put it?

STEVEN WRIGHT

Let everyone sweep in front of his or her own door and the whole world will be clean.

GOETHE

Contents

1

MY VAST FORTUNE

Before You Give It Away, You Have to Make It

1First Wad

Ill never forget being interviewed by Werner Erhardfor two hourson the subject of money. Not how to make it or invest it or any of the ordinary topics but how to be with it. I had no idea then what exactly the Est guru meant by this, though I was certainly impressed by dinner on his yacht the night beforehe knew how to be with money, I figuredand I have equally little idea now. I was even more baffled when viewers told me how much our closed-circuit TV conversation had helped them be with money. It had?

But Ill say this. I do like being with money.

I began accumulating my vast fortune in 1952, when my father gave me $5 for my fifth birthday. Five dollars was a lot more in 1952 than it is today (about $29 in todays money), and I would like to tell you I did something unusually precocious with it, or with the $6 I got when I turned six, or the $7 the year after that. Not to mention my allowance, which must have been in the twenty-five-cent range back then, before I learned to negotiate.

Instead, the money got spent, mostly down at Trellas, the local variety store.

One of the things I am famous in my family for having saidnot that I have any recollection of having said it, or that it took much to become famous in my familywas uttered when my grandmother asked me where all my money was. The bank, she was perhaps expecting me to say. Or the piggy bank. But it was in neither of these. Right now its in Trellas, I apparently said.

I had not yet learned to save.

But I did like money. For one thing, I liked numbers. For another, I was competitive, and doubtless saw money for what it isand practically all it is once you have more than you needa way to keep score. Let others be class president or veep; in high school, treasurer was my political calling. I liked counting the money. I liked the feel of a couple of hundred dollars in small bills in my pocket.

It wasnt about greedit wasnt my money, after all. And it wasnt exactly power. I didnt control how we would spend it. It wasnt even about floatsavings accounts all paid 3 percent back then, by law, so there was not a lot one could do with $200 overnight.

I guess it made me feel important?

2Uncle Lou

Growing up in Manhattan, and in Westchester on weekends, we led your basic blessed very-upper-middle-class life. We werent wealthyall the money that came in went right back out for orthodontia, tuition, the maid (in the Fifties, you didnt have to be rich to have a maid), the two cars, and on and on. Though I didnt know it at the time, there was a period of years when my mother would cry each month when she did the bills. Income was high, but so were expenses.

Uncle Lou, on the other hand, was wealthy. Short, fat and jolly, with a gold chain from his vest to his pants pocketI never saw him in anything other than a three-piece suithe looked like the rich uncle in the Monopoly game. Whenever he came to visit, the coins in his pocket positively jingleddazzling enough to a little kid, but then he would pull out a huge wad of silent green and hand me a dollar or two.

Loved Uncle Lou.

He also gave my brother and me a few shares of stockten shares of GM, twenty shares of General DynamicsI dont remember them all. (I do remember once, aged twelve, getting a cold call from a Merrill Lynch broker eager to discuss my investment needs.) In total, we must ultimately have sat steward over upwards of $2,000 in blue chips, perhaps half a dozen of them. I remember we would check their prices in the paper and graph them. Once I think we even made a trade. (In those days, the commission charged to trade ten shares of stock was higher than the commission today, if youre smart, to trade a thousand.) One thing for sure: we were no Warren Buffett or Jimmy Rogers or anything like that. But I guess we did get into the habit of seeing the glossy annual reports and receiving the occasional $12 dividend check.

If the idea was to mold little capitalists, it didnt work. My brother, summa cum laude from Harvard, went into academe with a decidedly anticapitalist bent (as what self-respecting Harvard grad of the time did not?). And Iwell, I was, at best, conflicted.

Yes, I liked money. And I loved collecting stamps and first-day covers and totting up their supposed value. But at the same time, I became aware that we were privileged, and it embarrassed me. I remember being at the Y for some sort of class (OK, OK, it was a puppetry class), aged ten or so, and the teacher that first day asking where each of us lived. Always wanting to be the first to answer, and this being an easy one, I blurted out: 860 Fifth Avenue. She turned red and spoke to me sharply about being little Mr. Big Shot or some such thing. I had no idea what she meant, or how she could possibly be criticizing me for answering her question. I realize now that I should have hesitated, looked down and said something like Sixty-eighth street, but its pretty cramped and we have no view, though its more than anyone deserves. Because while I took Fifth Avenue for granted, thats not where most people in America, or even New York, lived (though it was pretty cramped, andexcept for a magnificent few months when they tore down the building in front of us to build anotherair shafts were our only vista).

That moment stuck with me. I also found myself feeling extremely uncomfortable, as I got a little older, being served dinner by a black maid. What had I done to deserve being waited on by an adult this way? (Nothing.) The Sixties were upon us, Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney, not much older than me, were down in Mississippi getting killed (while I was being offered more pot roast), and my sense of injusticeperhaps honed by the tyranny of my older brother, whom I loved then after a fashion and surely love now, but you know what sibling rivalry can behad grown robust.