Pitch Publishing Ltd

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

Email:

Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

First published in the UK by Pitch Publishing, 2013

Text 2013 David Tossell

David Tossell has asserted his rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-90917-844-1 (print book)

978-1-909178-93-9 (eBook)

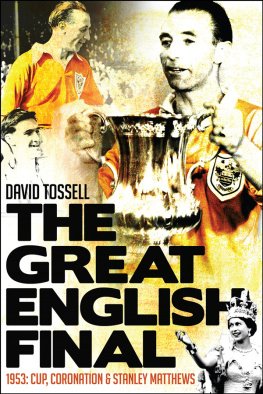

Cover design by Brilliant Orange Creative Services.

Typesetting by Pitch Publishing.

eBook conversion by eBookPartnership.com

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

P ROJECTS OF this nature rely heavily on the cooperation of many people and I am indebted in particular to those people who shared memories of the events and the era captured in this book. Their assistance is apparent throughout the text, although some who do not appear are also deserving of thanks: Andrew Dean and Gareth Moores at Bolton Wanderers FC, Frank Buckley, Mike Davage, Lynne Mollard, Haydn Parry, Richard Whitehead, the staffs at the British Newspaper Library, Colindale, and Blackpool Central Library and the various eBay sellers from whom I have purchased all manner of obscure items.

I owe enormous gratitude to the authors and editors of all the written material that has been the cornerstone of my research. I hope I have captured everything in this books bibliography, but my apologies for any inadvertent omissions. Additionally, I would like to thank Martin Johnes for permission to reproduce an extract from The 1953 FA Cup Final: Modernity and Tradition in British Culture, Aurum Press for use of an extract from Arthur Hopcrafts The Football Man, and David Goldblatt for allowing me to quote from his seminal work, The Ball is Round. Attempts to contact the excellent but now closed Bolton Revisited website proved fruitless, but I thank them nevertheless for the extract from Brian Farriss Cottontown Biography.

Thanks to Paul and Jane Camillin and Duncan Olner at Pitch Publishing, and Laura Wagg at the Press Association for help in sourcing photographs.

My family continues to be as supportive as ever and my wife, Sara, deserves special praise for barely raising an eyebrow when another box-load of vital research material appears in our spare room.

INTRODUCTION

The climax to the 1953 final may have been dramatic but there were more skilful Cup Finals in that era that are largely forgotten. It was the combination of different narratives that were not centred upon the actual play in the 1953 final that have ensured the games place in popular memory. Martin Johnes and Gavin Mellor, The 1953 FA Cup Final: Modernity and Tradition in British Culture.

I WENT there in search of ghosts, but the few I found were in unlikely places. Im not sure exactly what I expected to encounter on a bitterly cold November day at Boltons Reebok Stadium that would hark back to a sunny afternoon in May 1953, when Blackpools orange-jerseyed heroes had scored three times in the final 20 minutes at Wembley to fulfil the burning ambition of Stanley Matthews, the countrys most-famous and most-loved player. I certainly wasnt harbouring notions of seeing the spectre of the great winger materialise among the burly athleticism of a modern Premier League match. And no one had turned up expecting drama and excitement to match that 4-3 epic almost six decades earlier. I just knew that Bolton Wanderers home game against Blackpool, the clubs first meeting in Englands top division since 1968 42 years earlier had exerted a magnetism over someone studying the most famous of all matches between these teams.

Blackpools fans arrived dressed in orange, just as the famously flamboyant Atomic Boys had done at their clubs biggest matches in the years after the Second World War. Yet where once this band of brothers had worn colourful tailored suits, even oriental outfits with turbans, and had carried an orange-dyed duck as a mascot, their 21st century ancestors were more predictably attired in polyester replica jerseys emblazoned with the kind of commercial messaging unthinkable in the 1950s. With 90 minutes to go before kick-off, however, a frisson of nudges and nods outside the stadiums main entrance revealed that the sartorial spirit of the old-school fan was still alive. Barely a head remained unturned as BBC radio reporter and Its A Knockout legend Stuart Hall, a man synonymous with a more uncomplicated age, strode jovially through the glass doors wearing a thigh-length fur coat over mustard-coloured trousers. No duck, though.

Nor, on this day, was there anyone to remotely challenge the popularity of Matthews, the acclaimed Wizard of the Dribble, whose quest to claim a winners medal at Wembley at the third attempt had diverted the watching nation from its anticipation of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II a month later. Charlie Adam, a skilful Scottish midfielder who in bygone days could have been a devastating foil for Matthews as an old-fashioned wing-half or inside-forward, was the best Blackpool could offer. Appropriately he was the first man to step off the team coach, acknowledging the cheers as he walked briskly towards the players entrance.

Once the article in the matchday programme about the famous final had been absorbed, the contemporary football on display served to delete my black and white images of 1953 as effectively as if I had hit the off button on my DVD player while viewing the often-blurry BBC footage and been assaulted by MTV instead. It did seem appropriate, at least, to discover via an advertising hoarding that Boltons current full-backs heirs to the legacy of uncomplicated muscle men such as Tommy and Ralph Banks, Roy Hartle and Johnny Ball were sponsored by a tattoo parlour.

And there was a late comeback, although this time it was Bolton who scored twice in the final 15 minutes to achieve a draw against a visiting team who had no intention of sitting on a 2-0 lead away from home even when it would have been advisable and excusable. Quite right, the Blackpool of Mortensen and Matthews and skipper Harry Johnston would have said.

When, six months later, the teams reconvened at Bloomfield Road for the Seasiders last home game during their brief reacquaintance with English footballs top level it was on FA Cup Final day no less. The estimated 1953 final audience of ten million had been enough to finally convince the football authorities to move the sports biggest showpiece away from the concluding weekend of the League schedule. Yet now, for the first time since Matthewss finest hour, the Cup finalists would have to share their day, victims of the demands placed upon Wembley by the UEFA Champions League, the monolith of modern club football. As if to remind everyone of how things once were, the fates, the gods and some sub-standard defending contrived to produce a final score of Blackpool 4 Bolton Wanderers 3. Those ghosts had finally turned up.