PRAISE FOR EVEREST 1953

Mick Conefrey painstakingly studied the vast volume of detail surrounding the British expedition and can claim to have filled in some significant blanks on the map.

The Times

[The] cliff-hanging chapter endings had me feverishly turning pages long after midnight, eager to follow the team through danger, despair, and delight. Hugely enjoyable and highly recommended.

New Books

Fascinating [and] poignant. Conefrey has consulted obscure documents, interviewed all the right people and written a magnificent book.

Geographical Magazine

A gripping narrative underpinned by meticulous research.

Stephen Venables, Higher Than The Eagle Soars: A Path to Everest

Outstanding. Conefrey has found fascinating hitherto unpublished material and woven it cleverly into one of the most famous tales in mountaineering history. Eminently readable and valuable.

Julie Summers, Chair of the Mountain Heritage Trust

A highly readable and comprehensive account of a landmark mountaineering achievement.

Peter Gillman, The Wildest Dream: MalloryHis Life and Conflicting Passions

A thorough and well-researched book which tells the inside story of an often misunderstood expedition. Essential reading for anyone with a fascination for Everest.

Matt Dickinson, The Death Zone: Climbing Everest Through the Killer Storm

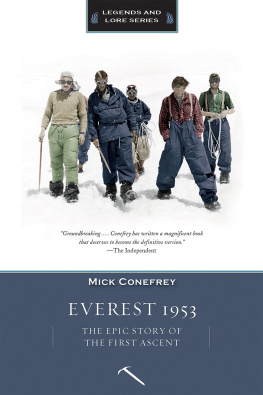

EVEREST 1953

THE EPIC STORY OF THE FIRST ASCENT

MICK CONEFREY

LEGENDS AND LORE SERIES

| Mountaineers Books is the publishing division of The Mountaineers, an organization founded in 1906 and dedicated to the exploration, preservation, and enjoyment of outdoor and wilderness areas. 1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201 Seattle, WA 98134 800.553.4453 www.mountaineersbooks.org |

First published by Oneworld Publications in the United Kingdom

Copyright 2014 by Mick Conefrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

Series design: Karen Schober

Book design and layout: Peggy Egerdahl

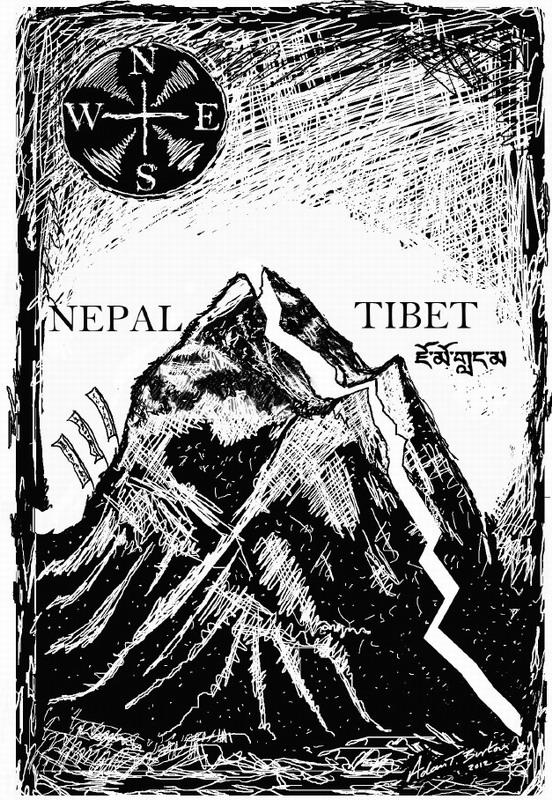

Illustrations by Adam T. Burton, Mick Conefrey

All photographs Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

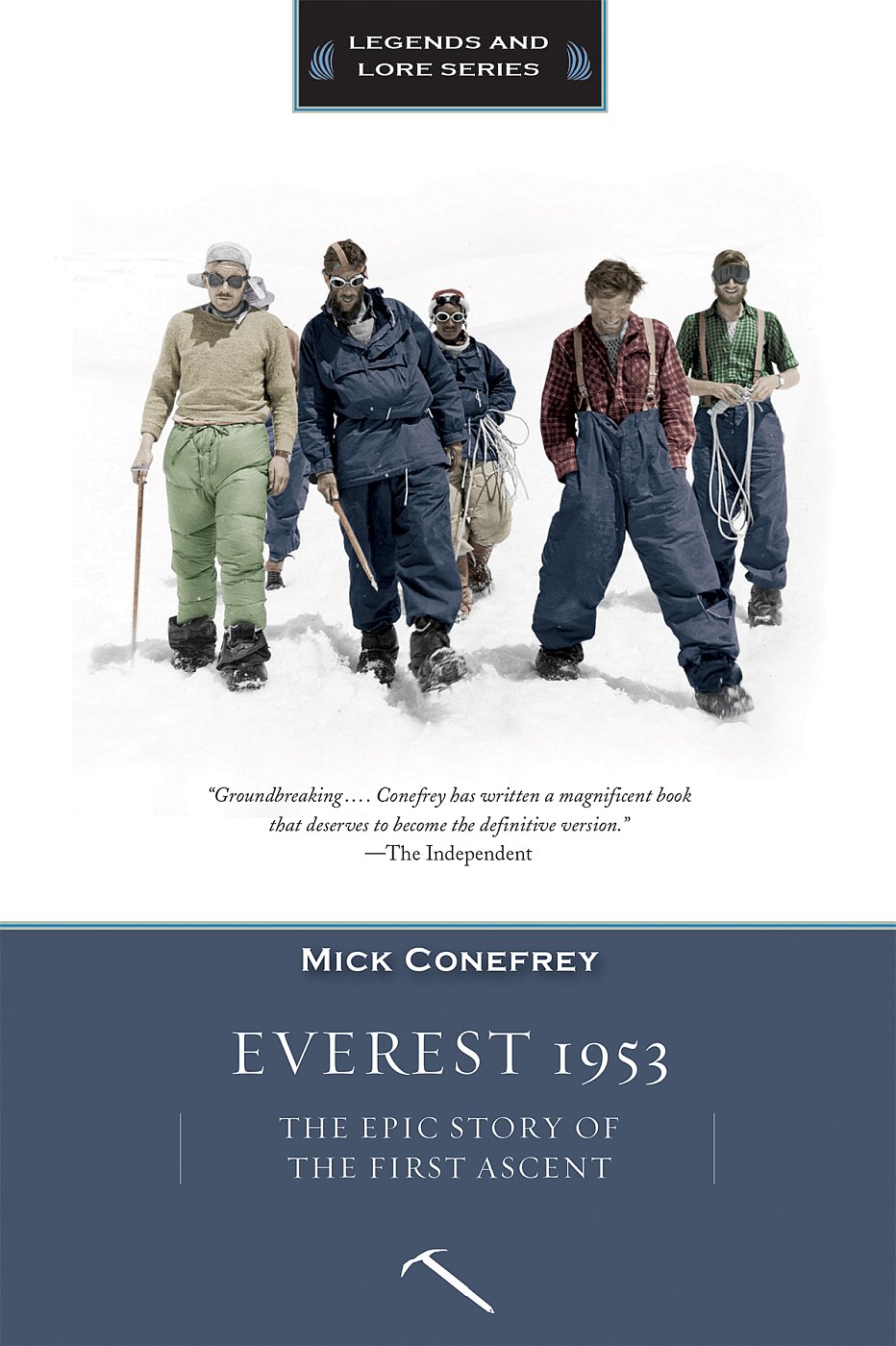

Cover photograph: Team members return to Camp IV after the ascent. Image coloring by StuartPolsonDesign.com.

Frontispiece: Tenzing Norgay on the summit of Mount Everest

A catalog record for this book is located at the Library of Congress.

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-59485-886-4

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-59485-887-1

To

Stella Bruzzi

What a strange and thrilling thing we have

let loosea very wonderful experience awaits us,

if we dont lose our heads.

John Hunts Diary, 3 June 1953

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE: OUR MOUNTAIN

FOR BRITISH CLIMBERS OF THE 1920s and 1930s, Everest was, quite simply, our mountain. It didnt matter that it was over 4500 miles away on the border of two of the most remote countries in the world, countries that werent even part of the British Empire. To paraphrase the poet Rupert Brooke, it was a foreign field that would be forever England. The British had measured it, named it, photographed it, flown over it and died on it. And so they assumed that one day a British mountaineer would be first to its summit.

Everest was measured in the mid-nineteenth century. It stands in the middle of the Himalayas, on the border of Nepal and Tibet and like many mountains, marks both a physical and a political boundary. Even though none of the surveyors ever set foot on its slopes, the Great Trigonometric Survey of British India was able to measure its height with astonishing accuracy from observation points over one hundred miles away. They estimated it to be 29,002 feet, 27 feet shorter than the current official height. Breaking with convention, instead of retaining its local name, Chomolungma, they christened it Mount Everest, in honour of George Everest, a former chief surveyor. Good geographer that he was, George Everest was not so keen on this act of cartographic piracy but the name stuck.

At about the same time, the sport of mountaineering was growing in the European Alps. British climbers were very competitive, making first ascents of many peaks in Switzerland and France and, in 1857, establishing the worlds first mountaineering society, the Alpine Club. Within a few years most of the high mountains of the Alps had been climbed and the more enthusiastic mountaineers had begun to look further afield for new challenges.

In 1895, Albert Mummery led a small expedition to Nanga Parbat, in modern-day Pakistan, the ninth-highest mountain in the world. His pioneering attempt ended in disaster when he and two Ghurkha assistants were killed by an avalanche. Albert Mummerys death did not act as a deterrent. Soon thoughts turned to Everest, the highest mountain in the world and therefore the greatest prize. For men like Lord George Curzon, the Viceroy of India between 1899 and 1905, climbing Everest was almost a national duty. He called Britain the home of the mountaineers and pioneers par excellence of the universe and actively campaigned for a British expedition under the auspices of the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society, which was set up in 1830 to promote exploration and advance geographical science. The two organisations joined forces to create the Everest Committee, to administer and raise funds for a British expedition.

Initially, it was hard to get permission from either Tibet or Nepal. Both, in theory, were closed kingdoms, which refused to allow foreigners to cross their borders. But such was Britains military power and prestige in the region that eventually the Tibetan government agreed to allow a British team to make the first reconnaissance of the north side of Everest in 1921. And so began what Sir Francis Younghusband called the Epic of Everest.

The reconnaissance expedition came back with mixed news. Everest was isolated, awesome and intimidating but not totally impossible. In 1922 and 1924 there were two large-scale attempts on the mountain. Both followed the same route to the northern side of Everest, via India and Tibet; both were remarkably successful, considering their very primitive equipment. In 1922 George Finch and Captain J.G. Bruce reached 27,300 feet and in 1924 Edward Norton reached 28,140 feet, less than 1000 feet from the summit. When two British climbers on the same expedition, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, disappeared close to the top, there was speculation that they might have reached the summit and perished on the descent.

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper