ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

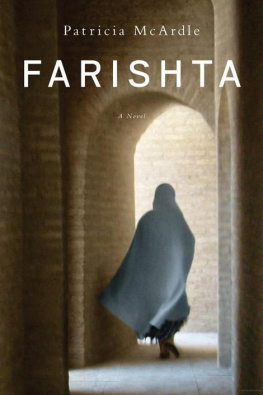

My daughters, Jennifer and Sabrina, encouraged me to take the assignment in Afghanistan, which provided the inspiration for this novel. Thanks, girls. You know I wouldnt have gone without your permission. Thanks to my good friends Kitty and Owen Morse, who urged me to write about my experiences when I came home, and to the friends and family members who were my faithful readers: Penny Hill, Martina Nicholson, Pat Currid and Jeane Stetson (who also provided ideas for the map), Mildred Neely, Rita Sudman, Judy Maben, and my daughter Jennifer. Two thumbs up for my remarkable editor at Riverhead Books, Sarah Stein, whose firm hand made Farishta so much better. My sincere gratitude goes out to the officers and soldiers who were my friends and protectors during the year I spent in Mazr-i-Sharf, with a special thanks to the three British Army colonels who commanded the PRT while I was there, and the five officers who patiently responded to my questions during the writing of Farishta: Tom Barker, Daniel Bould, Ross Carter, Harry Porteous, and Hugo Stanford-Tuck. Since Farishta is a novel and not a documentary, I do hope you fellows will forgive the artistic license I took with your detailed guidance on all things military. Thanks to poet and scholar Coleman Barks for introducing me to the magic of Rumis poetry during his visit to Mazr-i-Sharf in 2005. My highest praise is reserved for our brave young Afghan interpreters, especially one who will remain unnamedbut you know who you are. Tashakur.

My passion for solar cooking began during the year I spent in Afghanistan, where I saw children everywhere hauling piles of brush home for their mothers cooking fires. With the exception of the time I spent writing Farishta, I have dedicated the last four years of my life to promoting awareness of this remarkable technology. I plan to continue.

ONE

June 2004 WASHINGTON, D.C.

The first ring jarred me awake seconds before my forehead hit the keyboard. I inched slowly back in my chair, hoping no one had noticed me dozing off.

Narrowing my eyes against the flat glare of the ceiling lights, I scanned the long row of cubicles behind me. I was alone.

The second ring and the scent of microwave popcorn drifting in from a nearby office reminded me I was supposed to meet some colleagues for dinner and a movie near Dupont Circle at eight. It was almost seven thirty.

The third ring froze me in place when I saw the name flashing on the caller ID.

If irrational fear could still paralyze me like this after all these years, then perhaps it really was time to give up.

It wasnt only real danger that would accelerate my pulse and cause me to stop breathing like a frightened rabbit staring down the barrel of a shotgun. It was little things. Tonight it was a telephone call.

I forced myself to grab the receiver halfway through ring number four.

This is Angela Morgan, I said, struggling to suppress the anxiety that had formed a painful knot in my throat.

My computer beeped and coughed up two messages from the U.S. Embassy in Honduras. I ignored them and began taking slow, measured breaths.

Angela, youre working late tonight. Its Marty Angstrom from personnel.

Martys chirpy, nasal voice resonated like the slow graze of a fork down an empty plate.

He was stammering, obviously surprised that anyone in the Central American division at the State Department would pick up the phone this late on a Friday evening. I had apparently upset his plan to leave a voice message that I wouldnt hear until Monday morning.

Hello, Marty. Its been a long time. My heart was thundering. Is this a good news or a bad news call?

It depends, said Marty.

On what?

On what your definition of good is. He chuckled.

The wish list Id submitted to personnel for my next overseas diplomatic posting had been, in order of preference: London, Madrid, Nairobi, San Salvador, Lima, Caracas, Riga, St. Petersburg, and Kabul. Id thrown in Kabul at the last minute, thinking it would demonstrate that I was a team player and increase my chances for the London assignment. But they would never send me to Kabul, not after what had happened in Beirut.

Marty, please get to the point. Did I get London?

I could hear him breathing through his nose into the phone like an old man with asthma. He sounded almost as nervous as I felt. Not a good sign. Was I being sent south of the border again just because I spoke Spanish? But why would that make Marty nervous?

Before I retired or was forced out of the Foreign Service for not getting promoted fast enough, I was hoping for just one tour of duty in Western Europe. Foreign Service Officers, like military officers, must compete against their colleagues of similar rank for the limited number of promotions available each year. Consistently low performers are drummed out long before reaching the traditional retirement age of sixty-five.

I desperately wanted an assignment in London, but Id settle for Madrid. After all Id been throughI deserved it.

Well, youll be spending a lot of time with the Brits, Marty replied eagerly.

Meaning? I put him on speaker and began to rearrange the stacks of papers on my desk. My pulse and breathing were returning to normal.

Listen, Angela, I know you had some tough times a while back, but that was more than two decades ago.

Tough timesa dead husband and a bloody miscarriage. Yeah, those were definitely tough times, I thought, looking over at the small silver-framed photo of Tom and me. We were sitting on our bay Arabian geldings at the Kattouah stables near Beirut. Our knees were touching. His horse was nuzzling mine. We were laughing.

Tom and I had met for the first time in 1979 at a private stable in the Virginia hunt country, where wed arrived separately to rent horses for a few hours on the weekend. Although we were both studying Farsi in preparation for our first assignments as junior diplomats to the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, we had different instructors at the Foreign Service Institute. Our paths had never crossed until that warm summer morning, when the New Mexico ranchers daughter and the southern prep school boy discovered the first of their many common interests.

Ange, youre going to get kicked out of the Foreign Service in another year if you dont get promoted, warned Marty.

That was true. After the embassy bombing killed Tom, and I lost the baby a few days later, the Department had ordered me back to the United States to recover, but not for long. I stayed with my parents for three months, was given a low-stress desk job in D.C. for the following year, and was then expected to start Russian language training and take the assignment in Leningrad where Tom and I should have gone together.

During that two-year tour of duty in the Soviet Union, I had developed a taste for vodkawhich became my painkiller and therapist of choicean affinity that led to a series of less than stellar performance evaluations. After that disaster, I was exiled to Central and South American outposts where the Spanish Id learned from my mother would come in handy and nothing I did would have serious policy implications for the U.S. government.

My fathers prolonged illness and my frequent trips out west to see him had made it impossible for me to take any more overseas assignments for the past six years. My career had been dying a slow and painful death in a series of dead-end positions at State Department headquarters in Washington.

Continue, I replied, growing weary of Martys little guessing game.

You really need this promotion, Angela.

This conversation was becoming unbearable. I focused on my breathing, willing my anxiety not to resurface.