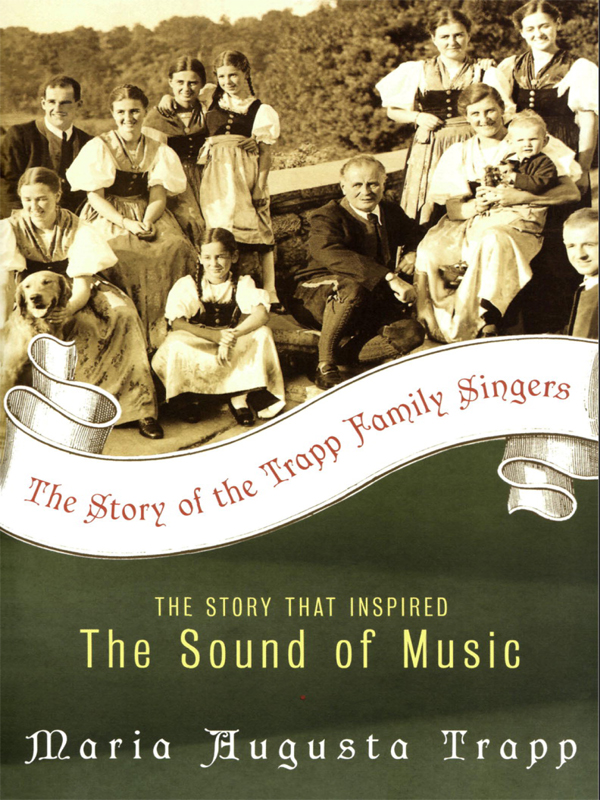

T O BE quite honest, this really is a foreword or an introduction, but Im so afraid that if I say so, you wont read it, as I never read forewords, and being so anxious that you do listen to what I want to tell you about the book before it starts, I ask you, foreword or no foreword, please read it just the same.

About fifteen years ago my family and I were visiting in Tirol. Our hostess was a famous writer.

Isnt it funny, she said one day, I never wrote a word in my life until after I was forty!

Thats quite incredible, we mused.

The next day we all went into a picturesque valley. On the way we saw a chapel greeting us from one of the wooded slopes.

Lets climb up there, said our hostess. Thats an interesting place. And so it was. The ancient building was of quaint architecture. Through the roof came a rope dangling down, which belonged to the bell in the little steeple. Playfully I took the rope to try out the sound of the bell.

Looking at our friend, I said: I wish I could become a writer, too, after Im forty! I meant that as a joke, and felt a little embarrassed when she didnt smile.

She looked at me rather queerly and said: Did you know the story?

I let the rope go and asked: Which story?

Well, she said, the people say that once in a hundred years it happens if someone rings this bell while pronouncing a wish, that wish, whatever it may be, will come true, provided the person is unaware of the legend. The people of this valley call it the wishing bell.

NoI didnt know this story, said I.

This was fifteen years ago.

While working on this book and writing down the memories of a family, it astonished, amazed, almost overwhelmed me to see how much lovegenuine, real lovewas stored up in one short lifetime: first, Gods love for us His children, the leading, guiding, protecting love of a Father; and as every real love calls forth love in return, it couldnt be any different here.

As we are singers, this story turned into a song, a canticle. Cantate Domino canticum novum, sings King David in one of his Psalms: Sing unto the Lord a new song. God has become for our age the great Unknown One. Things are blamed on the weather, on politics, on circumstances, on lack of vitamins, on inheritance; but they are rarely attributed to their one source. The Story of the Trapp Family Singers wants to be a canticle of love and gratitude to the Heavenly Father in His Divine Providence.

Cor Unum

Stowe, Vermont

Pentecost Sunday, 1949

Just Loaned

S OMEBODY tapped me on the shoulder. I looked up from the workbooks of my fifth graders, which I was just correcting, into the lined, old face of a little lay sister, every wrinkle radiating kindliness.

Reverend Mother Abbess expects you in her private parlor, she whispered.

Before I could close my mouth, which had opened in astonishment, the door shut behind the small figure. Lay sisters were not supposed to converse with candidates for the novitiate.

I could hardly believe my ears. We candidates saw Reverend Mother Abbess only from afar in choir. We were the lowest of the low, living on the outskirts of the novitiate, wearing our black mantillas, waiting with eager anticipation for our reception into the sacred walls of the novitiate. I had just finished the State Teachers College for Progressive Education in Vienna and had to get my Master of Education degree before the heavy doors of the enclosure would shut behind meforever.

It was unheard of that Reverend Mother Abbess should call for a candidate. What might this mean? Her private parlor was far at the other end of the old Abbey, and I chose the longest detour to go there, in order to gain time for examining my conscience. I was the black sheep of the community; there was no doubt about that. I never meant anything bad, but my upbringing had been more that of a wild boy than that of a young lady. Time and again I had been warned by the Mistress of Novices that I could not race over the staircase like that, taking two and three steps at a time; that I definitely could not slide down the banister; that whistling, even the whistling of sacred tunes, had never been heard in these venerable rooms before; that jumping over the chimneys on the flat roof of the school wing was not fitting for an aspirant to the novitiate of the holy Order of Saint Benedict. I agreed wholeheartedly each time, but the trouble was, there were so many new trespasses occurring every day.

What was the matter now, I thought, slowly winding my way down the two flights of old, worn steps, through the ancient cobblestoned kitchen yard, where the huge Crucifix greets one from the wall, and where the statue of Saint Erentrudis, founder of our dear old Abbey, rises above a fountain. Slowly I entered the cloister walk on the other side of the kitchen court.

Troubled as I was, searching through my laden conscience, I still felt again the magic of the supernatural beauty of this most beautiful place on earth. Twelve hundred years had worked and helped to make Nonnberg, the first Abbey of Benedictine Nuns north of the Alps, a place of unearthly beauty. For a moment I had to pause and glance again over the gray, eighth-century cloister wall before I ascended the spiral stairway leading to the quarters of Reverend Mother Abbess.

Shyly I knocked on the heavy oaken door, which was so thick that I could hear only faintly the Ave, Benedictine equivalent of the American, Hello, come in.

It was the first time I had been in this part of the Abbey. The massive door opened into a big room with an arched ceiling; the one column in the middle had beautifully simple lines. Almost all the rooms in this wonderful Abbey were arched, the ceilings carried by columns; the windows were made of stained glass, even in the school wing. Near this window there was a large desk, from which rose a delicate, small figure, wearing a golden cross on a golden chain around her neck.

Maria dear, how are you, darling?

Oh this kind, kind voice! Not only stones, but big rocks fell from my heart when I heard that tone. How could I ever have worried? No, Reverend Mother was not like that making a fuss about little things like whistlingand so a faint hope rose in my heart that she might perhaps talk to me now about the definite date of my reception.

Sit down, my child. No, right here near me.

After a minutes pause she took both my hands in hers, looked inquiringly into my eyes, and said: Tell me, Maria, which is the most important lesson our old Nonnberg has taught you?

Without a moments hesitation I answered, looking fully into the beautiful, dark eyes: The only important thing on earth for us is to find out what is the Will of God and to do it.

Even if it is not pleasant, or if it is hard, perhaps very hard? The hands tightened on mine.

Well now, she means leaving the world and giving up everything and all that, I thought to myself.

Yes, Reverend Mother, even then, and wholeheartedly, too.

Releasing my hands, Reverend Mother sat back in her chair.

All right then, Maria, it seems to be the Will of God that you leave usfor a while only, she continued hastily when she saw my speechless horror.

L-l-leave Nonnberg, I stuttered, and tears welled up in my eyes. I couldnt help it. The motherly woman was very near now, her arms around my shoulders, which were shaking with sobs.

Your headaches, you know, growing worse from week to week. The doctor feels that you have made too quick a change from mountain climbing to our cloistered life, and he suggests we send you away, for less than one short year, to some place where you can have normal exercise. Then it will all settle down, and next June you will come back, never to leave again.