Stevenson - Welsh Folk Tales

Here you can read online Stevenson - Welsh Folk Tales full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Gloucestershire;Wales, year: 2017, publisher: The History Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

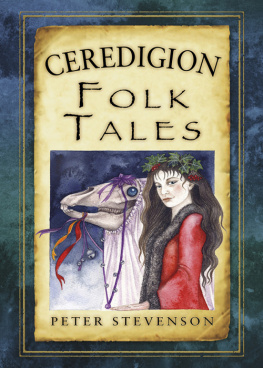

- Book:Welsh Folk Tales

- Author:

- Publisher:The History Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- City:Gloucestershire;Wales

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Welsh Folk Tales: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Welsh Folk Tales" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Welsh Folk Tales — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Welsh Folk Tales" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

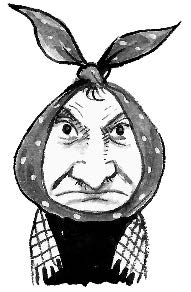

Mae hin bwrw hen wragedd a ffyn.

(Its raining old ladies with sticks)

Diolch o galon

Three songbirds who trod these paths before:

Maria Jane Williams, Glynneath;

Marie Trevelyan, Llantwit Major;

Myra Evans, Ceinewydd.

For my son, Tom,

and my mam and dad,

Edna and Steve

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

Peter Stevenson, 2017

The right of Peter Stevenson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8190 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CHWEDLAU

There is a Welsh word, Chwedlau, which means myths, legends, folk tales and fables, and also sayings, speech, chat and gossip. If someone says, chwedl Cymraeg?, they are asking, Do you speak Welsh? and Do you tell a tale in Welsh? Here is the root of storytelling, or chwedleua, in Wales. It is part of conversation.

The writer Alwyn D. Rees explains that when you meet someone in the street, you dont ask how they are, you tell them a story, and they will tell you one in return. Only after three days do you earn the right to ask, How are you?

One afternoon, I was talking to a friend in a shop when a storiwr spotted us through the window, did a double take, came in, and without pausing for breath, began. You know my next door neighbour? Miserable old boy, never had a good word for anyone, how his wife put up with him. Well Twenty minutes passed. He finished his tall tale, said, There we are, and left the shop. He had spotted a performance space and an audience, and he had a story stirring in his mind. There was no way of telling whether it was true or invented, and its likely he didnt know either. This happens all the time in the west. Takes forever to do your shopping.

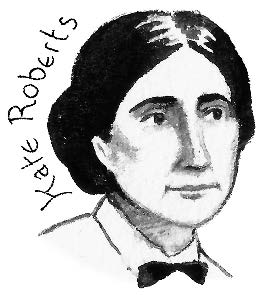

The Welsh story writer, quarryman and curate, Owen Wynne-Jones, known as Glasynys, told of a tradition of storytelling when he was a child in Rhostryfan in Snowdonia in the 1830s, and of his mother telling fairy tales in front of the fire. Sixty years later, the writer Kate Roberts, from nearby Rhosgadfan, thought Glasynyss recollection might well have been true of the people in the big houses, but there was no tradition of telling fairy tales amongst the cottagers. She added:

But there was a tradition of story-telling in spite of that, quarrymen going to each others houses in the winter evenings, popping in uninvited, and without exception there was story-telling. But these were just amusing stories, a kind of anecdote, and fellow quarrymen describing their escapades the skill was to make these amusing stories seem significant. I remember literary judgements being passed by the hearth in my old home: if anyone laughed at the end of his own story, or if he told the story portentously and nothing happened in it. Indeed, the way we listened to story-tellers like that was enough to make them stop half way, if they had enough sense to notice. But anyway, the tradition could have come indirectly to the quarrymen of my district, because many of them originated from Lln, where I believe traditional story-telling took place.

Pen Lln was renowned for its storytellers. They were farmers, poets, sea captains, garage mechanics, artists, mothers, quarry workers, crafts folk, preachers and teachers, and they moved effortlessly between gossip, fairy tale, politics, songs and criticism. Their fuel was humour.

They would tell you, When the gorse is in bloom, it is kissing time. There are three species of gorse, their flowering times overlap, so its always kissing time in Wales. When the pair of ceramic dogs in the window faced away from each other, it was a message from the lady of the house to the gentlemen of the village that her husband was away. And the tylwyth teg, the fair folk, were everywhere, small and otherworldly, tall and human, inhabiting the margins of our dreamworld, that space between awake and asleep, where time passes in the blink of a crows eye or freezes in an endless fatal heartbeat. Elis Bach lived at Nant Gwrtheyrn in the mid-1800s, and frightened anyone who met him. He was a farmer, a dwarf, a mothers son, and everyone agreed he was tylwyth teg.

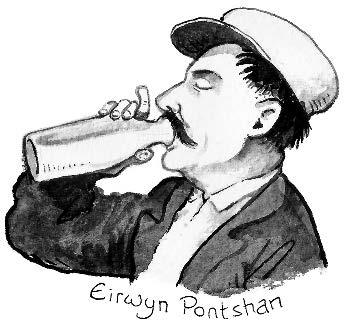

The storytellers spoke for their communities. Eirwyn Jones worked in a carpenters shop in Talgarreg, and was known after his home village, Pontshan. His stories were often scurrilous and hilarious. Gwell llaeth Cymru, na chwrw Lloegr, he said, Better Welsh milk than English beer. He once walked to an Eisteddfod in Pwllheli where he and a friend slept the night on a rowing boat in the harbour, only to find the morning tide had washed them out to sea. There they stayed, telling tales to the mackerel, till the tide flowed in again. At least he had time to wash his socks. Hyfryd iawn, he said, very lovely.

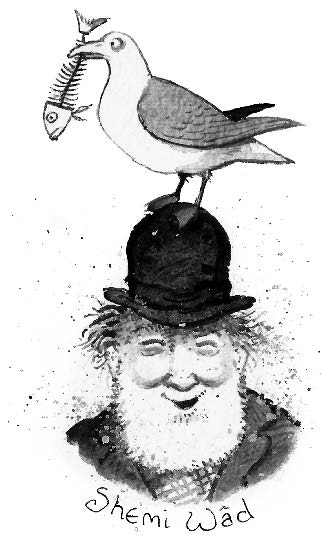

Old Shemi Wd sat outside the Rose & Crown in Goodwick spinning yarns to the children about how the seagulls had carried him over the sea to America.

Twm or Nant from Denbigh travelled from village to village performing interludes from the back of his cart. Myra Evans collected fairy tales and gossip from her family and neighbours in Ceinewydd, filled sketchbooks with drawings of local characters, and documented a way of life rooted in chwedlau.

In lime-washed farmhouses in the hills, conjurers recited charms from spell books and kept potions in misty brown bottles. Harpers disappeared into swamps, dreamers vanished into holes in the ground, drowned sailors called to long-lost lovers and castles were preserved as bees in amber. Stories, history and dreams entwined as memory.

Into this land came travelling people. The Romani arrived in the mid-1700s, with tales of Cinder-girl and Fallen Snow, ladies darker by far than Cinderella and Snow White. Somali sailors came to work in Cardiff docks in the 1800s and stayed, saying, A person who has not travelled does not have eyes. Refugees fled Poland after the Second World War and settled on Penrhos Airfield near Pwllheli, where their families still live in the Polish Village. The Cornish traded with Gower and worked in the lead mines, Italian POWs became farmhands and married local girls, and Breton men cycled the lanes selling onions. All the while, the Welsh emigrated, fleeing poverty and loss of land, becoming miners and missionaries, searching for new hope in the Americas, Australia and Asia. Their stories travelled with them. There are echoes of old Shemis tall tales in the Appalachian Liars Competitions. Honest, there are.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Welsh Folk Tales»

Look at similar books to Welsh Folk Tales. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Welsh Folk Tales and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.