Taylor family. - A Necessary End

Here you can read online Taylor family. - A Necessary End full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: United States, year: 2019, publisher: Independent Publishers Group : Jones Street Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Necessary End

- Author:

- Publisher:Independent Publishers Group : Jones Street Books

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- City:United States

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Necessary End: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Necessary End" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Necessary End — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Necessary End" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A Necessary End

Nick Taylor

For Mom and Dad, of course;

For Harley Jones, who was also a good son;

And for my nephew, Doug Tudanger, his parents, and the rest of my new family.

Contents

Of all the wonders that I yet have heard,

It seems to me most strange that men should fear;

Seeing that death, a necessary end,

Will come when it will come.

from Julius Caesar, by William Shakespeare

My mother wrote her own obituary, and my fathers, too. I opened one of her letters in May of 1983 expecting the usual news of friends and family, the weather and what shed been reading lately. Instead, I read: Clare Unger Taylor died A space followed, implying that I should add the circumstances. The notice continued with a modest, straightforward description of her life, a gentle life of mild accomplishment. She had done the same with my father: John Puleston Wotton (Jack) Taylor died

They died within months of each other some time later, and I took the obituaries out and added what was needed and sent them to the papers she had listed. Still later, I scattered my parents ashes on the sea. But I return often to the time those obituaries introduced, for what I learned of death and life, and continuity, the unending flow of one into the other. It was a period of eight years.

My parents were then in their mid-seventies. My mother was short in stature and nearsighted, and sweet-tempered despite the appearance of a pugnacious chin that quivered when she set her jaw. She had a university degree, from Michigan, and had worked as a reporter, but the thing she was most proud of, other than me and helping to start two libraries, was that she was the first woman who dared to wear pants in the stuffy expatriate community of the small Mexican town where they lived in retirement for several years. Jocotepec has never been the same, she liked to say. I always thought my mother was born before her time. My father, on the other hand, was born too late. He was a Victorian at heart, in love with order, blind to his own quirks but quick to censure others. He was compact and sinewy, bawdy and ill-tempered. He could roar with laughter and the next minute turn to fierce, protective anger. He worked as a land surveyor and a draftsman, but I considered his true calling the delicate wood-block prints he made and the sailboat he built from plans he drew himself. I was thirty-seven. I was their only child.

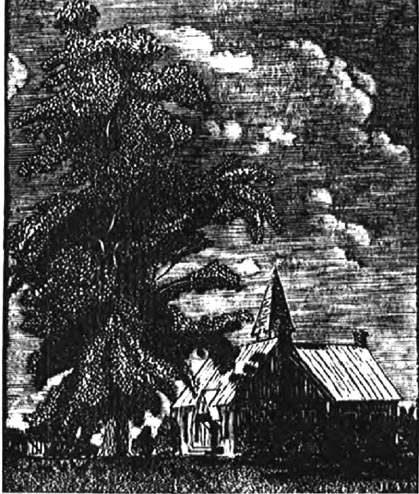

They lived that year in a small town, Waynesville, that lies between the Smoky Mountains and the Blue Ridge in western North Carolina. They had lived there when I was born and moved several times, always to return. This time their home was in a high-rise for the elderly. The building was new and made of sturdy red bricks, and the politicians had gotten up on a flatbed truck and dedicated it with speeches about the time my parents moved in early in the year. Their apartment was on the fifth floor. From the living rooms one wide window you could see, across the street, a large maple tree that turned flame red in autumn and a church ground bordered by a low stone wall. The wall made me think about appendicitis. I had been a first grader when a burning stomachache forced me to leave school to meet my mother at a doctors office. I had gotten as far as the wall, where Mom found me, hugging my knees in pain, and hours later my appendix was removed. That was in 1952.

They took a Florida vacation in 1953, and Mom fell in love with Fort Myers Beach, a resort island and shrimping port on the lower Gulf Coast. We moved that fall, when I was seven, and I grew up and finished high school there. They returned to North Carolina after I finished college, in 1967. They stayed five years, then moved to the Mexican village of Jocotepec, near Guadalajara, in 1972. Four years later they moved back to southwest Florida and into their first high-rise for the elderly, a building on the Caloosahatchee River in Fort Myers called the Presbyterian Apartments. I thought they would stay there. Dad was seventy then, and Mom was sixty-seven. But the restlessness set in after seven years. They decided to return again to North Carolina, and moved just a few months before I opened the mail to find that Mom had written their obituaries.

Waynesville, like everyplace, had changed. The Mount Olive Baptist Church didnt hold its Sunday dinners anymore. The whole town had spread outward to the bypass, and the welcoming Gateway to the Smokies sign that once hung over Main Street had been taken down. The downtown newsstand now sold the New York Times on Sundays. It was a convenient four-hour drive from my home in Atlanta to Waynesville. Now, after all their moving, surely my parents would stay until they died.

The new year was barely underway when I was helping them pack to return to Mexico. I was against the move. Dad took digitalis for his heart, and Mom wasnt what she used to be. Shed had an accident a few months earlier, and although shed been indignant when the judge sent her to driving school, it had clearly been her fault. They were determined to go regardless.

A light rain was falling that February morning, increasing my sense of gloomy foreboding. In winter the southern mountains are impassive, as if theyve turned their backs and dont give a damn; I felt their rejection in my mood. My wife, Barbara, and I carried suitcases and boxes from their apartment to their big old Plymouth. A row of old men and women sat watching in the lobby, country people who had their own reasons for resenting the circumstances in which they found themselves. They had been corralled from farms and cabins by well-meaning children like myself who came gravely every Sunday to take them out to dinner. Snuff bulged their lips and the womens stockings were rolled down around their calves and they stared at us with the flinty, unforgiving eyes of prisoners watching an escape. They planned to die there; why should anyone be allowed to leave alive? My heart should have soared, but I was thinking of myself.

My parents had been a big part of my life when I was growing up; that is to say, our relationship was necessary. We were not the kind of family that played touch football or went to reunions or even embraced each other heartily. Partly, I think, it was because we were rootless. My father was born in England, my mother on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. I had an uncle I wouldnt have recognized and cousins I had never met. I went to work after college, lived in three cities in four years, got married, settled in Atlanta, divorced, remarried. Over time I grew used to loving my parents coolly, with a minimum of muss and fuss. I thought it was inconsiderate of them to move to Mexico at their age, when I was beginning to worry about them. It would have been much easier on me if like the others, they had chosen to simply sit and wait for death.

At last the car was loaded. We stood together in the parking lot, awkward at the moment of departure. Dad was hopping from foot to foot, anxious to get started. Mom had a pained wistfulness in her blue eyes, a look of endurance. I brushed my pursed lips against my mothers lips. I hugged my father, felt him hang on a second longer than we were accustomed to. The forces arrayed against them, these two people who had gotten old, seemed dangerously potent all at once. Mom settled behind the steering wheel. The car engulfed her. She had to tilt her head back to see down the long hood, which raised her chin and emphasized it. Dad wouldnt drive. I couldnt remember the last time he had driven. Too goddamned much trouble, he said. Your mothers a good driver, let her drive. He didnt even have a license anymore; he had let it lapse as a way of denying the states power over him. He took the passenger seat and right away set about fussing. He would have preferred to fly ahead while I drove Mom to Mexico, as he had the last time while we slogged it, but this was my punishment for his insistence. You play, you pay; you want to move to Mexico, you by God dont take the easy way of getting there while your family does the dirty work. I eyed him sitting there and felt some satisfaction at the fifteen hundred miles ahead of him. Serves you right, you mean old fart, I thought. Hed found the short trip to my wedding in Atlanta too much for him the year before. Then he turned a sweet smile upon me. Goodbye, Nick, he said, and patted my hand resting on the door.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Necessary End»

Look at similar books to A Necessary End. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Necessary End and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.