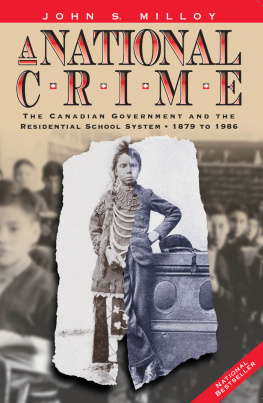

To the lovely Janine, without whose patience and support I could not have writte n these words Preface Those familiar with my work will agree that, for better or worse, God and the Indian is a departure for me. Let me tell you how the play came to be, from t he beginning. I had never really intended to write a play about the residential school issue. It seemed everybody and their grandmother was pulling their own page out of that book and I didnt want to be part of that trend, having never been to such a school. The voices of many other authors, who personally experienced that tragic period, were also, I thought, more authentic than my own. My voice is that of the humorist; I am known primarily for but not limited to a lighthearted and satirical take on the Native experience.

Cultural genocide and institutionalized sexual abuse do not lend themselves to humour very well. Nor sh ould they. One spring day I was chatting with the artistic director of a Native theatre company where I was the new writer-in-residence (new being a somewhat inaccurate term to describe me, as I had served as the writer-in-residence for this company twenty years earlier). During an initial meeting, the AD stated unequivocally her aims for my residency. Drew, I dont want you to write something fun and enjoyable, she said. I want you to write something bleak and dep ressing.

Maybe Im exaggerating. In truth, she said something closer to, I know you can be funny. I want to see you be serious, forgetting that the year before I had been shortlisted for the Governor Generals Award for In a World Created by a Drunken God , a serious drama and one of my most successful works to date. I remember being surprised by this request. Very rarely, other than in a direct commission, have I been told specifically what I can and cannot write. I already had a whole play planned out in my head, waiting to spring forth and fill the seats of that theatre.

I cant help but wonder if this AD has ever told any of her more serious and sombre playwrights, Okay, I know you can be serious. But I want to see if you can be funny. Prob ably not. I decided to take the bit in my teeth and accept the challenge. In order to please the boss, I tried to think of the most depressing and painful thing happening in the Native community that I could write about. Thus the idea for God and the Indi an was born.

I realize this may sound like a frivolous or superficial approach to the issue, but in the end it wasnt. Sincerely motivated to write this story honourably and with respect, I threw myself into it. If I screwed up, if I was flippant, if I was disrespectful, I would definitely hear about it. And rightly so. At the time of my residency with the theatre, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings were being held across the country and, lets face it, you cannot be Native in Canada without knowing someone who was personally affected by the residential school system. Research was easy.

Coming up with the story was easy. Being honest and humble in telling this story was more challenging but essential. I began to write. Some months later, I submitted the first draft. It was a two-act play, admittedly with some dark humour in it, about a man trying to find closure. Either by accident or by act of God, he sees a man from his past a man who was an Anglican minister at the residential school he attended decades earlier and who had abused him.

He follows the minister to his office and demands accoun tability. One of the most surprising things I learned in my research is that many residential school survivors arent looking for vengeance or retribution. They just want to be heard. They just want to be believed. And thats what Johnny, my central character, wants from the now assistant bishop. Johnny wants to hear the man acknowledge and own up to his actions.

Who wouldnt? A week or so later, I heard back from the AD. She thought I should cut my full-length play to one act. Not really agreeing with her, but knowing that she who signs the cheques is seldom wrong, I gutted my play. That is to say, I ripped twenty or thirty pages from the middle of the script, without understanding why, and resubmitted it. Strangely, another week or two went by before I heard back from the theatre company. Now they were not interested in my serious play and wished me good luck submitting it e lsewhere.

Feeling a little angry and petulant after this incident, I set God and the Indian aside and forgot about it. Almost completely. I tucked it away in some obscure file on my computer and in my mind, concentrating instead on other stories and tales that were waiting to be written, with hopefully a lot less baggage. The play stayed buried for several years until I ran into one of the former board members of the theatre company. He asked whatever happened to that play about residential school. Apparently he liked what I had written and was puzzled why it had never gone any further.

It took me a moment to remember what play he was talki ng about. Remembering its resonance, I subsequently went home, dug it out (the two-act version), reread it, and recognized its definite possibilities. One opinion is not the only opinion. So, getting a second breath of interest, I decided to submit it to other theatre companies that were interested in my work. Thats where Donna Spencer at Vancouvers Firehall Arts Centre comes into the picture. She read it and liked it, and a new dialogue between AD and playwrig ht began.

But there was one minor problem. No older male First Nations actors were available for the role of Johnny, the residential school survivor. But miraculously, for some reason unknown to me, the magnificent Tantoo Cardinal had heard about the play and expressed interest in playing the role of Johnny. Now, I am sure you realize the difficulty inherent in that pos sibility. Donna asked how determined I was that the character of Johnny be male. The physical, emotional, and sexual mistreatment in those schools favoured neither male nor female students, and the repercussions of that abuse has permeated generations of Natives, regardless of gender.

So, intrigued, I decided to explore the concept of a female Johnny. The more I thought about it and rewrote the script, the more the female Johnny came into focus and the more excited I became. Tantoo, as Johnny, opened up unexplored character possibilities and I found myself writing new and exciting material that I had not even considered during God and the Indian s first i terations. To make a long story slightly shorter, after some rewrites the play was produced in spring 2013 at the Firehall Arts Centre. It was marvellously envisioned and directed by Renae Morriseau, staring Tantoo and Michael Kopsa. The final play script you now hold in your hands.

In these pages I ask some questions, but answer only a few of them; others I leave up to you t o decide. This is an angry play. This is a healing play. This play is many things. I only hope I have done the topic and the people justice. I hope I was serio us enough.

Drew Hayden Taylor Curve Lake, Ontario February 2014 God and the Indian was first produced on April 7, 2013, at the Firehall Arts Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia, with the following cast and c reative team: JOHNNY : Ta ntoo Cardinal GEORGE : Michael Kopsa Director: Re nae Morriseau Set and Lighting Designer: Lau chlin Johnson Costume Designer : Alex Danard Artistic Director: Donna Spencer Stage Manager: Rob in Richardson CHARACTERS JOHNNY : Native woman, panhandler, residential school survivor, early fifties GEORGE : Caucasian, assistant bishop in the Anglican Church, former teacher at an Anglican residential school , mid-sixties SETTING The assistant bishops office, located in an old mansion that has been convert ed to offices TIME Early 2000s ACT ONE Lights up on a modest but well-appointed office in a heritage mansion that has been converted to offices . A large wooden desk sits in one corner. On the wall behind it hangs a painting of Christ with children gathered around him. An overstuffed chair, a mini-bar, a bookshelf, and a small couch and coffee table furnish the rest of the room. It is Saturday morning. Scattered about the office is evidence of a small party from the night before: folding chairs leaning against one wall, wrapping paper from presents, trays of food in various states of consumption, and, directly in front of the door, a large cardboard box filled with empty wine bottles.