X-15 Diary

The Story of Americas First Space Ship

Richard Tregaskis

This book is an attempt to present verbal photographs of hundreds of men and women at work on one of our important space projects. There are thousands more involved in our other space efforts, just as demanding and exacting, and many as dangerous too. To the men and women I name and follow at their work, and to the faceless thousands trying just as hard on other sectors of the War Against Space, this book is respectfully dedicated.

Contents

Photographs

The First Flights

February 26, 1959. With Dick Barton, from the Public Relations Department of North American Aviation, and Raun Robinson, one of the two assistant chief engineers on X-15, I went down to the West High Bay section of the factory to get my first look at the X-15.

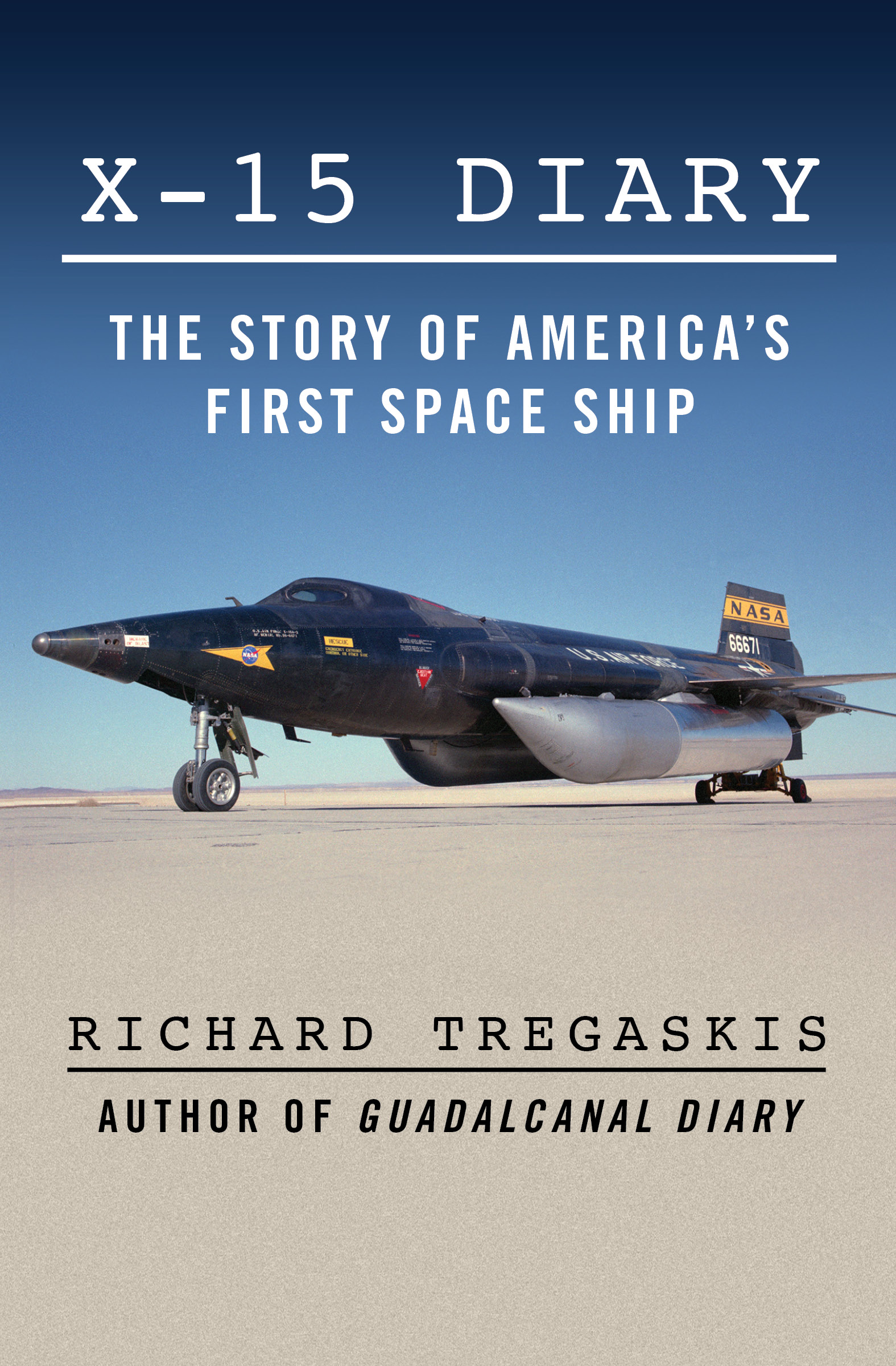

Its a big, light, open factory bay, with two X-15s lined up in tandem. The one closest to the airfield is much farther on, constructionwise, than the other. It looks just about finished, where the other one still has the appearance of a skeleton, as if the basic structure were still being put together. These are Birds Nos. 2 and 3. Bird No. 1, the first of the three in the $121.5 million program, has already been taken (by truck) up to Edwards Air Force Base, where pretty soon it will make its first flight under the wing of a B-52 mother ship.

Bird No. 2the one closest to the field here in the West Baywill be ready for its first public roll-out tomorrow, Dick Barton said. In a week or two it will probably be trucked up to Edwards.

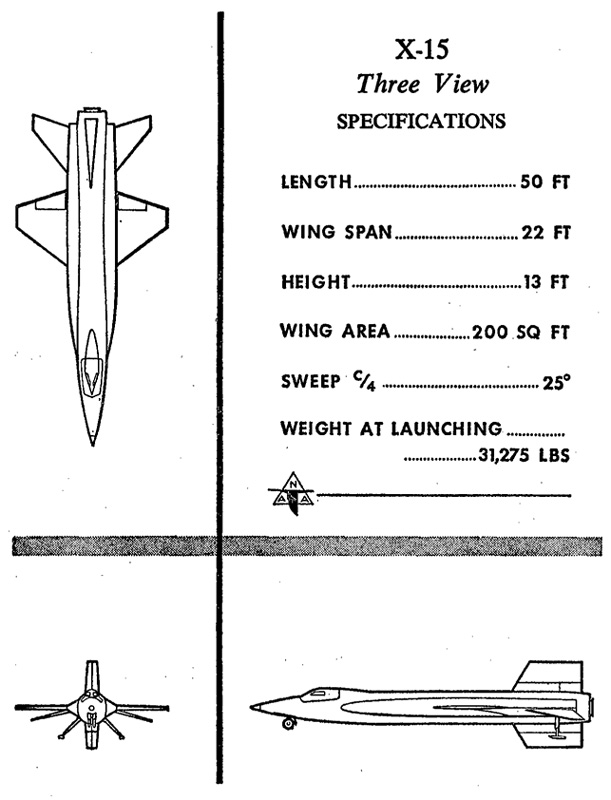

Bird No. 2 looks very impressivesleek, black, powerfula missile with stubby little wings and a cockpit on top of the nose. When we came into the bay the cockpit canopy was up and a group of technicians in sports shirts clustered around that part. The canopy was being raised and lowered. One man held a flashlight so he could check something in the relative darkness when the canopy was lowered. The slit eyes of the cockpit windows are made of dark blue glass, to keep the glare of space to a minimum.

We went to the cockpit and climbed up the work ladder beside it. The plane seems very solid, sleek, and well finished. The metal of the exterior is largely Inconel X, a high nickel-steel alloy especially resistant to heat.

Most of it is tanks, Dick said, and pointed to the middle of the ships body. There, under the slick black surface, are the two huge tanks, in tandem, that make up most of the fuselage. They will hold 1,200 gallons of water alcohol, the fuel, and 1,000 gallons of liquid oxygen or lox, the oxidizer needed to burn it. There are other, smaller tanks, for hydrogen peroxide, helium, and nitrogenall the gases needed to make the various systems of the bird work.

We looked into the cockpit. There is a huge aluminum brace set up as a kind of semicircle behind the head of the pilot.

Thatll hold his head if there is buffeting, Dick said.

We looked at the steel seat, which can be blown clear of the aircraft by an explosive charge if the pilot has trouble.

The seat is the pilots office, Dick said. Hell stay with it, even if he ejects. He wont leave it until hes well into atmosphere.

He pointed out the metal wings that flanked the chair. If the pilot bails, the wings will fold out and give him some stability so he wont tumble so much. I looked into the big gap behind the cockpit, an empty compartment with scores of switches set up on one wall. Raun Robinson indicated a large black box of instrumentation sitting beside it on the factory floor.

About 400 pounds of instruments will be put into the compartment, he said. Some will connect with the instrument panel, some will send dope to the ground. (The total weight of the instrumentation in various compartments is 1,300 pounds.)

He took me around to one of the stubby little wings and pointed out a kind of grid pattern of holes in the lower side of the black surface.

These taps are for pressure, he said. And Barton explained that this is a research aircraft, that the main purpose of it is to explore the close reaches of space, so there are 790 taps on it to record temperature and pressure.

We stopped at the nose, a solid-feeling cone of black metal. Raun said: Its a heat sink. Itll soak up the heat of re-entry. He explained that the heat here would get up as high as 1,200, depending on how fast the bird is flying when it comes back into atmosphere. Some other parts of the bird, the belly and the underside of the wing, will get nearly as hot as the nosethat is, if it comes back into atmosphere in the proper attitude, nose down. But if something goes wrong with the space controls and it re-enters upside down, or tumbling, lots of the other parts are going to get excessively heated. If that should happen, the pilotll be in plenty bad trouble, Dick Barton said.

I asked Dick about the reason for painting the ship black. Id heard that black paint was supposed to emit more of the re-entry heat than a white color. The engineers have a fancy word for this. They call it high emissivity.

The early aircraft in our Air Force series of rocket planes were painted for visibility in light colors like the light orange of the X-1 in which Captain (now Lieutenant Colonel) Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier in 1947. But the engineers on X-15, confronted with more outer skin heating than ever before, wanted a paint which would give off a maximum of the ships heat as it hit atmosphere at high speed. They had the answer after heat-chamber tests. [Paul F. Bikle, director of the NASA facility at Edwards Air Force Base, points out that black generally has better emissivity, and that the X-15 was also painted black to provide a uniform color over the materials of various colors in the structure, thus giving a minimum of temperature differences.]

February 27. Today was the time for roll-out of Bird No. 2. A bright, clear, warm morning. On the smooth concrete expanse outside the West High Bay Barton and I saw a knot of men and women gathered around the bird. The bird, even in the sunlight, has a sinister look about itthat slick, black body with the two bulges (side tunnels) like muscles along its flanks, the nose as sharp as a mosquitos. Its as sinister as a mosquito would be if the mosquito weighed sixteen tons and had the horsepower of the Queen Mary, and carried a man on its back.

Beside the X-15, this morning, sat the big metal mass of the ejection seat. It had been taken out of the cockpit area, and blinds hung up inside the cockpit to mask it from rubbernecks. Some of the stuff inside is still, apparently, on the classified listalthough Newsweek magazine has already printed a photograph of the supposedly secret instrument panel, the one with the stable-platform (gyro) gauges on it. As in a war, theres always an officious type who hasnt the correct word about what is or isnt on the secret list.

Near the ejection seat stood a man hi the Silver Suitthe Air Force calls it MC-2which the pilots lined up to fly the X-15 will wear. The man in the suit today was not a pilot, but Rex Martin, a technician from North Americas Human Factors Department, demonstrating the equipment. The people gathered around the X-15 were stockholders, Dick Barton said. Most of them were men, middle-aged or older, wearing business suits, quite formal for the bright Los Angeles sun. A company guide was answering questions.