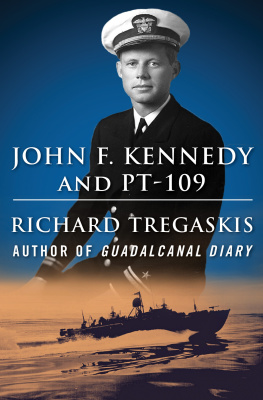

To a dedicated and gifted leader, J. F. K.

A Lieutenant Joins the PTs

At 1:43 on the morning of Sunday, August 9, 1942, the cannonading began. Men of the First Marine Raider Battalion saw the flashes against the rainy night sky to the southwest. But they did not stir from their sleeping places, for it was a rule among the marines that anything moving at night would be shot at.

After two days of hard fighting, the Raiders had virtually secured the tiny island of Tulagi, across the bay from Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. Colonel Merritt A. Red Mike Edsons First Marine Raider Battalion had encountered suicidally determined resistance from the tough defending Japanese forces dug into the caves and ravines of jungly Tulagi. And through the night there had been occasional crackling outbursts of small-arms fire as marines fired at isolated enemy snipers, real or imagined. But for the most part, the island of Tulagionce the seat of British colonial government in the Solomon Islandshad been quiet until the cannonading broke out.

The men looked up from the foxholes they had dug, or peered out the windows of the few remaining shacks which had not been smashed by the fighting. Tired eyes, gleaming white in faces begrimed by two days of sweating, fighting and suffering in the jungle, watched the greenish-white flashes. Ears keyed to the slightest of sounds listened to the steady brroom-brroom of the distant cannons.

As the Raiders listened and watched, they realized that a major sea battle was being waged somewhere between Tulagi and Guadalcanal. They sensed that their future was being settled among the green flashes and metallic thunderings of the naval guns. As the crashing of the guns increased in tempo, it also grew louder, and seemed to be moving toward Tulagi. Then, at about 2:30 A.M ., the flickering lights began to fade in the sky, and the thunder of guns grew fainter. No one on Tulagi knew whether the lull in the heavy firing meant that the engagement was over or would renew itself with mounting fury a second later.

Not until years later, when the war was over, were the facts of this First Battle of Savo Island known. Japanese Admiral Mikawa, in his flagship Chokai, had led a marauding force of Japanese cruisers and destroyers into The Slot between Guadalcanal and Savo Island. Here he had pounced upon the unaware force of American cruisers and destroyers supposedly guarding the transport ships which had just landed the Marine forces invading the islands of Guadalcanal, Tulagi, Gavutu and Tanambogo.

Mikawas forces had quickly made expert torpedo and gunnery attacks, and left four Allied heavy cruisers burningthe United States ships Quincy, Astoria and Vincennes, and the pride of the Australian Pacific navy, the Canberra. During the night, all four were to sink, with a loss of more than 1,000 lives. The engagement was the first of the many violent sea battles to rage in the waters around the Solomon Islands.

Back in the United States very little information was reaching the public beyond the brief Navy communiqus reporting that marines had landed in the Solomon Islands at Guadalcanal, Tulagi and Gavutu. But at the very moment when the marines on Tulagi were wondering about the meaning of the naval action out there in the dark, a small group of men at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York was making its own contribution to eventual victory for America.

At the Navy yard, 10,000 miles away from the Solomons, it was 11:30 A.M ., bright midday. And the crew of PT Boat 109 (PT meaning Patrol Torpedo) had just taken a hard-earned lunch break from their work of fitting out PT-109 at the Brooklyn yard. PT-109 was one of the latest models of a so-called miracle weaponan 80-foot plywood-and-mahogany speedboat armed with torpedoes and machine guns. General Douglas MacArthur had said this weapon might have made a considerable difference in the defense of the Philippines if it had been available in much larger quantities. Now, four months after the fall of the Philippines to the Japanese war machine, mass production of the PT boats had just begun.

The 109 boat was the sixth of a new class of PTs designed to be mass-produced at the Elco Boat Works at Bayonne, New Jersey. As the crewmen of the 109 boat stopped for lunch, nine more boats in the same series were coming off the Elco production lines, and a hundred more would be built in the next year.

Like Kaisers Liberty ships, which were built in large sections like automobile parts and assembled on a giant factory line, the Elco 80-footers came together in two major pieces, hull and deckhouse. After the decks were in, a giant hoist lifted the 30-ton hull and swung it into the water. From there it was guided to the giant, hangar-like fitting-out building where the hull would be made into a fighting boat with the addition of two dual .50-caliber gun mounts on the right forward and left rear sections of the deckhouse. Four torpedo tubes, two even with the bridge structure amidship, and two on the afterdeck, were also installed on the boat. Like fat steel crayons, these were oriented fore and aft, so that they were aimed generally in the same direction as the boat. When an attack was to be made, they would be trained out a few degrees. In this way the torpedoes, when fired, would clear the side of the boat. Then, once in the water, they would be trained by gyroscope mechanism so that their course would follow the direction the boat had been pursuing. Besides the .50-caliber dual mounts and the torpedo tubes, some of the boats were equipped with two depth-charge mountings on the bow.

With the mountings of the armor-plated deckhouse, the rakish windshield with its base of armor-plate, the guns, the four torpedo tubes, and the depth-charge cradles, the little plywood destroyers began to look more formidable.

In July of 1942, PT-109 was ready to leave the Elco Boat Works. At the Bayonne fitting-out basin, a crew went aboard the spic-and-span new motor torpedo boat and started the short trek down Newark Bay toward New York Harbor and Brooklyn.

At the Brooklyn Navy Yard the fitting out of the PT boat was completed and she was taken on a series of shake-down cruises. PT-109 had been routinely assigned to Ensign Bryant L. Larson as part of a squadron of six new boats under the command of Lieutenant Commander Clifton B. Maddox. The squadron was as yet unassigned but rumor had it that they would be sent to action in the South Pacific.

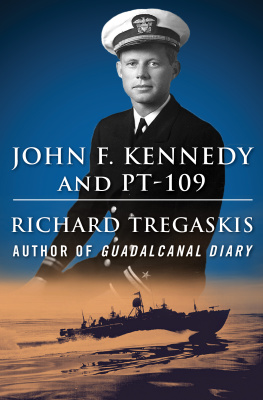

At this time the Navy skipper who was later to win fame for his command of PT-109 had not the slightest inkling that she would ever be his boat. A tall, slim, intense young man with gray eyes and a pug nose, he was attending the Naval Reserve Officers Training School at Northwestern University, Chicago. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was one of tens of thousands of young American men wearing the single gold bar of ensign.

This young freckle-faced, mop-haired ensign differed from the average, however, in that he bore a famous name. His father, Joseph P. Kennedy, a Boston multimillionaire, had until recently been American Ambassador to the Court of St. James, at that time considered Americas top diplomatic post.