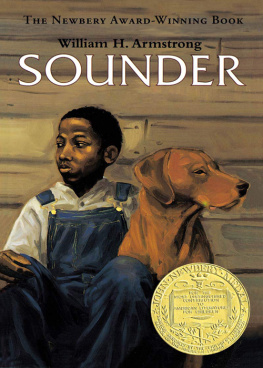

WILLIAM H. ARMSTRONG

THE TALL MAN stood at the edge of the porch. The roof sagged from the two rough posts which held it, almost closing the gap between his head and the rafters. The dim light from the cabin window cast long equal shadows from man and posts. A boy stood nearby shivering in the cold October wind. He ran his fingers back and forth over the broad crown of the head of a coon dog named Sounder.

Where did you first get Sounder? the boy asked.

I never got him. He came to me along the road when he wasnt moren a pup.

The father turned to the cabin door. It was ajar. Three small children, none as high as the level of the latch, were peering out into the dark. We just want to pet Sounder, the three all said at once.

Its too cold. Shut the door.

Sounder and me must be about the same age, the boy said, tugging gently at one of the coon dogs ears, and then the other. He felt the importance of the yearsas a child measures agewhich separated him from the younger children. He was old enough to stand out in the cold and run his fingers over Sounders head.

No dim lights from other cabins punctuated the night. The white man who owned the vast endless fields had scattered the cabins of his Negro sharecroppers far apart, like flyspecks on a whitewashed ceiling. Sometimes on Sundays the boy walked with his parents to set awhile at one of the distant cabins. Sometimes they went to the meetin house. And there was school too. But it was far away at the edge of town. Its term began after harvest and ended before planting time. Two successive Octobers the boy had started, walking the eight miles morning and evening. But after a few weeks when cold winds and winter sickness came, his mother had said, Give it up, child. Its too long and too cold. And the boy, remembering how he was always laughed at for getting to school so late, had agreed. Besides, he thought, next year he would be bigger and could walk faster and get to school before it started and wouldnt be laughed at. And when he wasnt dead-tired from walking home from school, his father would let him hunt with Sounder. Having both school and Sounder would be mighty good, but if he couldnt have school, he could always have Sounder.

There aint no dog like Sounder, the boy said. But his father did not take up the conversation. The boy wished he would. His father stood silent and motionless. He was looking past the rim of half-light that came from the cabin window and pushed back the darkness in a circle that lost itself around the ends of the cabin. The man seemed to be listening. But no sounds came to the boy.

Sounder was well named. When he treed a coon or possum in a persimmon tree or on a wild-grape vine, his voice would roll across the flatlands. It wavered through the foothills, louder than any other dogs in the whole countryside.

What the boy saw in Sounder would have been totally missed by an outsider. The dog was not much to look ata mixture of Georgia redbone hound and bulldog. His ears, nose, and color were those of a redbone. The great square jaws and head, his muscular neck and broad chest showed his bulldog blood. When a possum or coon was shaken from a tree, like a flash Sounder would clamp and set his jaw-vise just behind the animals head. Then he would spread his front paws, lock his shoulder joints, and let the bulging neck muscles fly from left to right. And that was all. The limp body, with not a torn spot or a tooth puncture in the skin, would be laid at his masters feet. His masters calloused hand would rub the great neck, and hed say Good Sounder, good Sounder. In the winter when there were no crops and no pay, fifty cents for a possum and two dollars for a coonhide bought flour and overall jackets with blanket linings.

But there was no price that could be put on Sounders voice. It came out of the great chest cavity and broad jaws as though it had bounced off the walls of a cave. It mellowed into half-echo before it touched the air. The mists of the flatlands strained out whatever coarseness was left over from his bulldog heritage, and only flutelike redbone mellowness came to the listener. But it was louder and clearer than any purebred redbone. The trail barks seemed to be spaced with the precision of a juggler. Each bark bounced from slope to slope in the foothills like a rubber ball. But it was not an ordinary bark. It filled up the night and made music as though the branches of all the trees were being pulled across silver strings.

While Sounder trailed the path the hunted had taken in search of food, the high excited voice was quiet. The warmer the trail grew, the longer the silences, for, by nature, the coon dog would try to surprise his quarry and catch him on the ground, if possible. But the great voice box of Sounder would have burst if he had tried to trail too long in silence. After a last, long-sustained stillness which allowed the great dog to close in on his quarry, the voice would burst forth so fast it overflowed itself and became a melody.

A stranger hearing Sounders treed bark suddenly fill the night might have thought there were six dogs at the foot of one tree. But all over the countryside, neighbors, leaning against slanting porch posts or standing in open cabin doorways and listening, knew that it was Sounder.

If the wind does not rise, Ill let you go hunting with me tonight. The father spoke quietly as he glanced down at boy and dog. Animals dont like to move much when its windy.

Why? the boy asked.

There are too many noises, and they cant hear a killer slipping up on them. So they stay in their dens, especially possums, because they cant smell much.

The father left the porch and went to the woodpile at the edge of the rim of light. The boy followed, and each gathered a chunk-stick for the cabin stove. At the door, the father took down a lantern that hung on the wall beside a possum sack and shook it. Theres plenty of coal oil, he said.

The boy closed the door quickly. He had heard leaves rattling across the frozen ground. He hoped his father didnt hear it. But he knew the door wouldnt shut it out. His father could sense the rising wind, and besides, it would shake the loose windowpanes.

Inside the cabin, the boys mother was cutting wedge-shaped pieces of corn mush from an iron pot that stood on the back of the stove. She browned them in a skillet and put them on the tin-topped table in the middle of the room. The boy and the three younger children ate their supper in silence. The father and mother talked a little about ordinary things, talk the boy had heard so many times he no longer listened. The crop will be better next year. Therell be more day work. The hunting was better last year.

This winter the hunting was getting worse and worse. The wind came stronger and colder than last year. Sometimes Sounder and his master hunted in the wind. But night after night they came home with an empty brown sack. Coons were scarcely seen at all. People said they had moved south to the big water. There were few scraps and bones for Sounder. Inside the cabin, they were hungry for solid food too. Corn mush had to take the place of stewed possum, dumplings, and potatoes.

Not long after supper, Sounders master went out of the cabin and stood listening, as he always did, to see if he could hear the cold winter wind beginning to rise in the hills. When he came back into the cabin, he took off his blanket-lined overall jacket and sat behind the stove for a long time. Sounder whined at the door as if he were asking if someone had forgotten to light the lantern and start across the fields of dead stalks to the lowlands or past the cottonwoods and jack oaks to the hills. The boy took Sounder some table scraps in a tin pan. As Sounder licked the bottom of the pan it rattled against a loose board in the porch as if somebody were walking across the floor.