For Irene

CONTENTS

Guide

Put me to doing, put me to suffering.

Methodist Prayer

REV. ASA K. JENNINGS

Architect of the rescue

LIEUTENANT COMMANDER HALSEY POWELL

USS Edsall

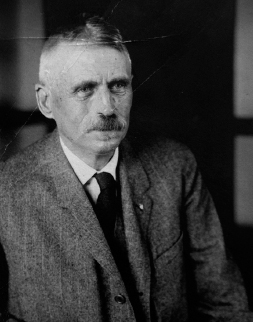

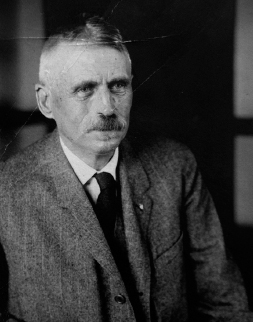

ADMIRAL MARK L. BRISTOL

U.S. High Commissioner/Constantinople

CAPTAIN ARTHUR J. HEPBURN

Naval Chief of Staff/Constantinople

GEORGE HORTON

U.S. Consul General/Smyrna

DR. ESTHER POHL LOVEJOY

Saving lives on the Smyrna Quay

LIEUTENANT COMMANDER J. B. RHODES

As a young officer

LIEUTENANT AARON S. MERRILL

Navy Intelligence

GHAZI MUSTAPHA KEMAL

Supreme Turkish commander

CAPTAIN IOANNIS THEOPHANIDES

Conspires in rescue

T his is a true story. In creating a narrative account of the events at Smyrna, I have drawn on the reports, letters, and diaries of U.S. naval officers, declassified American intelligence reports, and American and British diplomatic cables. I also have employed the first-person accounts of American missionaries and relief workers and British sailors and officers who witnessed the fire and its aftermath. It has been my good fortune to receive access to the personal papers and letters of key figures in the storyAsa Kent Jennings, Halsey Powell, Alexander MacLachlan, Caleb Lawrence, and George and Nancy Horton. Some of this material had not been previously available. The principal contribution of this book is the astonishing story of the American rescue at Smyrna based on the testimony of those who participated in it. For the broader context against which the forward story unfolds, including background on the Paris peace talks and their immediate aftermath, the discovery of oil in the Near East, the life of Mustapha Kemal and the religious slaughter that swept Turkey in the early twentieth century, I have drawn on the work of numerous eminent scholars and experts including Michael Llewellyn-Smith, Richard Hovannisian, Daniel Yergin, and the late Andrew Mango, who generously responded to my questions in the final year of his life.

Some landscape and seascape descriptions in the book are mine based on numerous visits to key locations in the story. I have relied on contemporaneous newspaper accounts of the catastrophe at Smyrna when those accounts lined up with observations of others who were present.

For the towns and cities of the Ottoman Empire, I have used the names that would have been used by Americans in the storySmyrna and Constantinople, for example, rather than the Turkish names Izmir and Istanbul. For the names of Turkish figures, I have chosen English spellings that seemed easiest for English speakers to pronounce. I have rendered Turkish words that have letters that do not appear in the English alphabet in ways that create similar sounds. For example the Turkish paa appears as pasha. It is pronounced pash-AH.

I use the term Near East because it was the term used at the time of these events. The Near East included the Balkan countries and Greece, Asia Minor (meaning the Turkish peninsula between the Black and Mediterranean Seas, and otherwise known as Anatolia), Syria, Lebanon, and Palestinethe so-called Levant, the eastern rim of the Mediterranean down to Egypt. The Near East also embraced Persia and the Arabian Peninsula. The contemporary term Middle East came into general use after the events of this story. I use Turkey and the Ottoman Empire interchangeably as was common in the period. The Republic of Turkey came into existence in 1923.

At the time of these events, most Moslems in Turkey had one name; occasionally a second name was added. Names were typically accented on the final syllable: Must-ta-PHA Ke-MAL. Among the Turks, bey was an honorific meaning sir. Pasha was a general or high-ranking statesman. Efendi was a title of respect for a man of high status or education. Hanum meant lady or Madame.

In 1922, the ethnic Greeks of the Ottoman Empire used the Julian calendar; the Turks used the Islamic calendar; and the Europeans and Americans used the Gregorian calendar, which is the calendar used here.

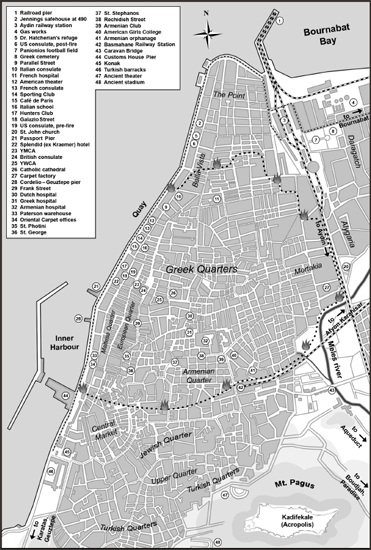

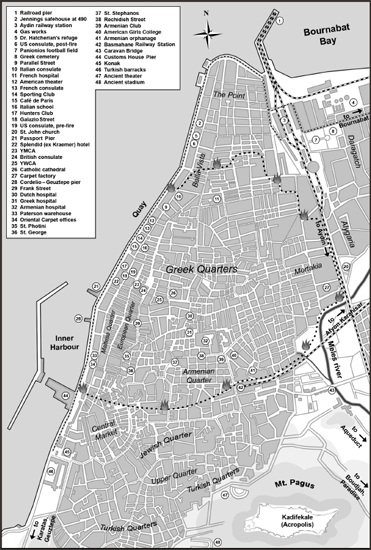

Map by George Poulimenos

The eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea including the Balkans, Greece, Turkey (along with major rail lines) and Russia.

Map courtesy of the Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Wednesday September 13, 1922

S myrna was burning, and U.S. Navy captain Arthur J. Hepburn prepared to evacuate the one hundred twenty-five Americans under his protection. A destroyer dispatched from Constantinople stood by in the harbor waiting to take the Americans aboard.

In his navy whites, which seemed to gather the dying light of the Mediterranean dusk, Hepburn was a smudged and sweating emblem of American prestige. He stood on the waterfront only a few blocks from the massive fire that was consuming the city and waited for his sailors to take their positions before he gave the command to begin the evacuation. The American citizens waited in a movie theater on the citys Quay, a two-mile promenade that traced the sweeping edge of the harbor.

This was no ordinary city fire. Huge even by the standards of historys giant fires, it would reduce to ashes the richest and most cosmopolitan city in the Ottoman Empire. The fire would ultimately claim an even more infamous distinction. It was the last violent episode in a ten-year holocaust that had killed three million peopleArmenians, Greeks, and Assyrians, all Christian minoritieson the Turkish subcontinent between 1912 and 1922. It would also serve as a marker of the end of the Ottoman Empire.