Praise for The Gathering Place

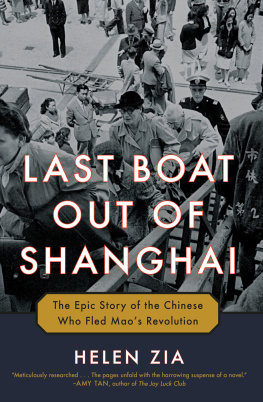

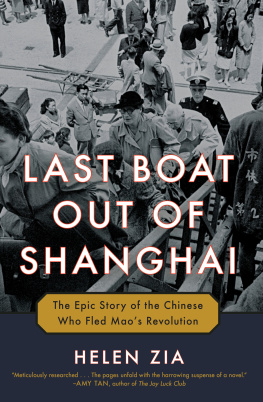

The Armenian Diaspora has a long history, and even today more Armenians live outside the borders of the Armenian Republic than inside the country. China has also been frequented by Armenian migrants and expatriates throughout recorded history. However, their numbers always remained limited, and the world's most populous country did not become host to a long-established and vibrant Armenian community to attract the attention of historians of Armenian Diasporan communities. The Gathering Place promises to rectify that omission. It focuses our attention on a number of colorful Armenian individuals, who had escaped in their youth both the Armenian Genocide and the turbulence of the Communist revolution in Russia, found refuge and started a new life in Shanghai, only to endure further hardship during the Japanese invasion, the Second World War and finally the Chinese Civil War.

Dr. Ara Sanjian, Director, Armenian Research Center, University of Michigan-Dearborn

A wonderfully vivid and concise history of the triumph and tragedy of the Armenian people through two millennia, combined with the lively and readable narrative of one of its most unique diasporan communities. T he Armenian social club in old Shanghai is a charming commemoration to both the joy and strength of our culture.

Kenneth Khachigian

Armenians will immediately feel at home reading Sergoyans The Gathering Place . Wherever Armenians have migrated, they have rebuilt their ethnic community as soon as they founded a club, which perpetuates their heritagelanguage, fine arts and literature.

I was surprised to learn that Armenians migrated East, to Shanghai, for example. Being an Armenian who migrated westward for a new homeas 99% of Armenians didI had assumed 100% of us went West. This aspect may fascinate other readers, too.

Sergoyan has recorded the Shanghai Armenians innumerable contributions; it seems Diaspora Armenians have been valuable everywhere they form communities outside the boundaries of Armenia. Sergoyan is proving the adage, Once an Armenian, always an Armenian. Or, wherever an Armenian migrates, he will build a club, where his identity will be born again.

Shahan Shahnour, a respected Armenian novelist, has said, The world will lose nothing if Armenians disappear from the face of the earth. But the world will gain a great deal if Armenians are allowed to survive and make use of their creative powers. The Armenians of Shanghai have done this.

Aida Kouyoumjian, author of Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide

Introduction and Acknowledgments

This book originated as a collection of stories that my parents, relatives and their friends told to their children over the years at holiday tables and gatherings.

Years later, working from a set of audiotapes and notes, I added details and background to give readers a general sense of the era and setting. I recognize that some sections read like travelogues of exotic places while others read like popular history, merely touching on the monumental events that helped shape the modern world. The goal was to spark the interest of future generations who know little about the Old World or the immigrant experience.

I do not pretend to be a scholar of history. I have tried to tell these stories in the voices of the storytellers, in a simple manner that I hope will both educate and entertain. I leave it to others to provide a more scholarly study of the migration of people from Eastern Turkey after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

When I contacted friends and family who might corroborate the details and add to the background information, people volunteered more stories. These interviews added even more flavor and new perspectives on the Armenian Diaspora, particularly concerning those who migrated into the Orient.

In writing the book, I benefited from the support of many people. I wish to thank the Ohanjanian family in Canada, the Lukin family in Brazil, the Asryantz family in Russia, the Pashinian family and the Toumanian family in the U.S. for their contributions of pictures or information. I also owe a major debt, which I am happy to acknowledge, to Virginia Meltickian, Edwin Gerard, Yervand Markarian, and the Western Diocese of Armenian Church for their contributions.

Finally there are three special debts that I wish to acknowledge. First and foremost to my sister, Nina, who plays a part of the stories, helped with the initial drafts, and encouraged the work as it developed; to my publisher, Catherine Treadgold, whose suggestions made the stories more readable and coherent; and as always, to my wife, Lynda, who managed many of the draft details and made it possible for me to concentrate and focus, while suffering my moods and bad manners.

For e w o rd

The Gathering Place: Stories from the Armenian Social Club in Old Shanghai is many things at once. It is part oral history, part family history, part loving tribute to an intrepid generation that has passed on. It exists somewhere between history and memory. This is not a scholars archival history, but an account of events as remembered and retold long afterwarda gift of memory from one generation to the next.

The book is based on interviews with Nadine and George, Armenian refugees who made their way to the United States by way of Shanghai during some of the most eventful years of the twentieth century. Nadine and George met and married in Shanghai; in these pages their story is augmented by stories from members of their social circle. Their memories are placed within a rich historical context that illuminates the cosmopolitan nature of life in interwar and wartime Shanghai: Armenian refugees from Turkish oppression encounter Russians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution and European Jews escaping Nazi persecution. The story of Nadine and George is an extraordinary American story but ultimately it transcends any single place. It helps us see the twentieth centuryas much as the twenty-firstas a global century.

Raymond Jonas, PhD

For Andrenik and Lisa F ay

Prologue

T he woman smiled as she looked up from her book and glanced out the window of the observation deck of the third railway car. Visibility outside was zero. The entire terrain outside her train window was what Americans called a whiteout . Except for an occasional break in the swirling snow , there was nothing to see.

Nadine was smiling at the foul weather because the whole reason for taking the train had been to see the country. She had been raised in Asia and loved the mountains of Siberia, Manchuria and China. As a teenager she would go hiking and rock - climbing regularly with her brother and his friends. She wanted to see the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming and Colorado that she had read about in books and magazines. The writers described the high plains country of America as very special, very rugged, unlike anything else in the world. She had only just arrived, y et here she was, in an early winter snowstorm on a stalled train somewhere in Wyoming on her way to Chicago and there was nothing to see.

She had left San Francisco late afternoon of the previous day to be finally reunited with her family. She was eager to see her children. It had been a year and she feared that her little daughter had already forgotten her. After finally coming to America at the port of San Francisco, she had made arrangements to fly to Chicago overnight and arrive the next day. But her friends had convinced her that the train was far better. First of all, the train is safer , said her friend Nina. Y ou can relax, read a book, and watch as the beautiful scenery pass es by, she added. Its really the only way to travel.

Nadine looked out the window again as the train began to speed up and plow through the snowstorm. The only scenery was a few feet pas t the railway right - of - way. It was hard to believe that the engineer could see anything ahead. But she wasnt particularly concerned. The train she was on was the City of San Francisco a streamliner, one of the most modern diesel trains of its day. The only disappointment was the severe snowstorm that had hit in the mountains , unusual for early November.