Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

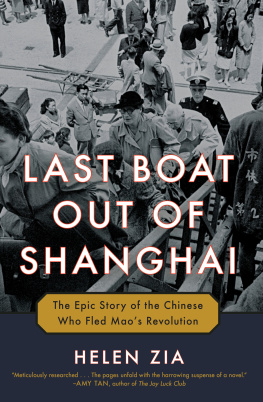

Last Boat Out of Shanghai is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2019 by Helen Zia

Map copyright 2019 by David Lindroth Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

B ALLANTINE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN- P UBLICATION D ATA

N AMES: Zia, Helen, author.

T ITLE: Last boat out of Shanghai: the epic story of the Chinese who fled Maos revolution / Helen Zia.

D ESCRIPTION: New York: Ballantine Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

I DENTIFIERS: LCCN 2018036197 | ISBN 9780345522320 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525618867 (ebook)

S UBJECTS: LCSH: ChinaHistoryCivil War, 19451949Refugees. | Political refugeesChinaHistory20th century. | ChineseForeign countriesHistory20th century. | ChinaEmigration and immigrationHistory20th century. | Shanghai (China)History20th century.

C LASSIFICATION: LCC DS777.542 .Z53 2019 | DDC 951.04/2dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018036197

Ebook ISBN9780525618867

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Barbara M. Bachman, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Daniel Rembert

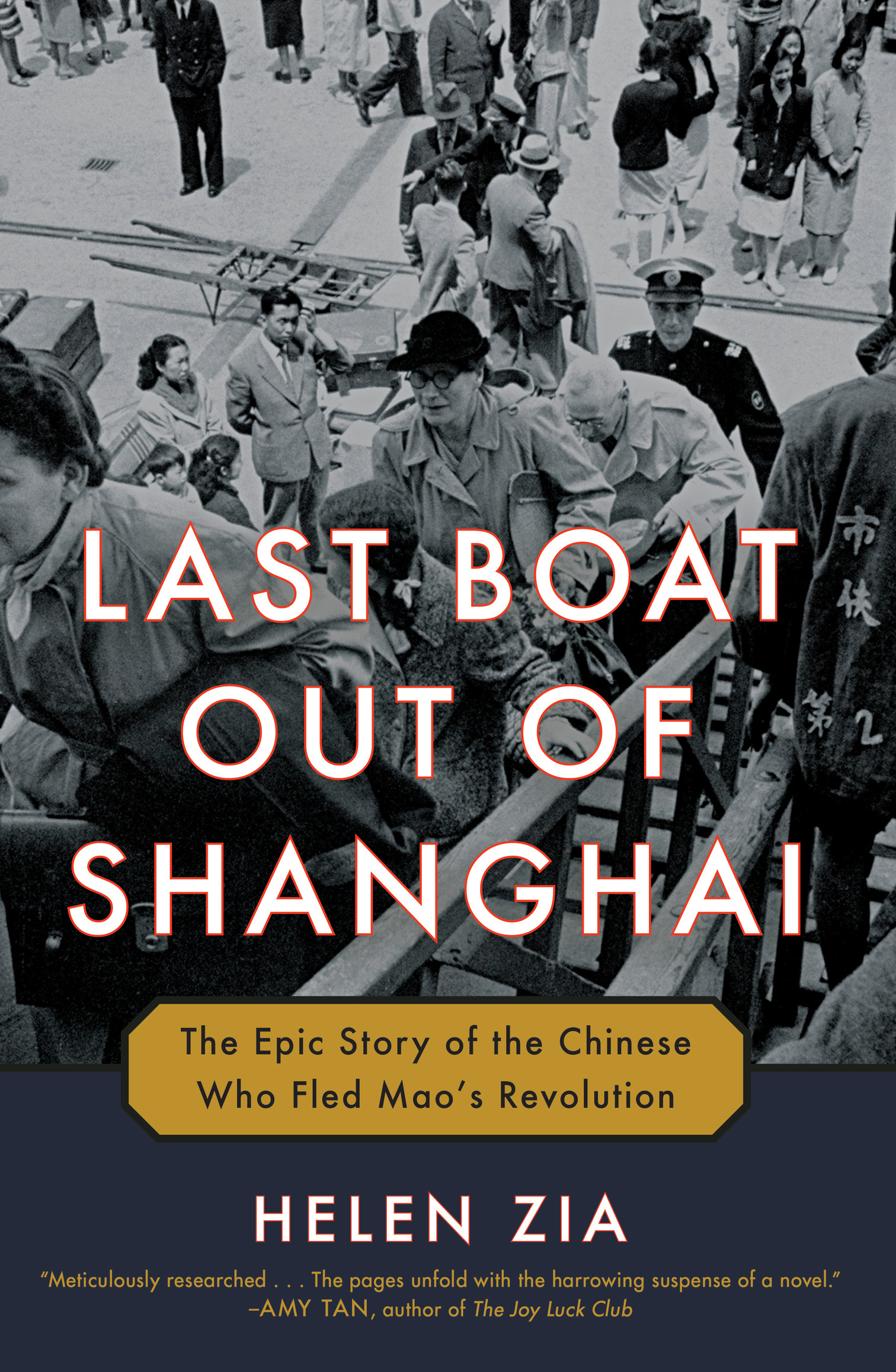

Cover photograph: Jack Birns/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

v5.4_r2

ep

Running away is one of our nations characteristics. We are very good at it. The best strategy for getting out of a bad situation is to run away. It may be the only way you can save yourself. If you dont follow this rule, you end up suffering.

The two characters tao nan mean running away from difficulty. When transposed, it is nan tao and means difficult to run away. Looking back at those who tried to run away by plane or train or ship, many ended up getting killed in accidents. It was indeed difficult for them to run away.

EXCERPT TRANSLATED FROM LUN YU [The Analects Fortnightly], CHINAS LEADING LITERARY MAGAZINE, IN ITS SPECIAL ISSUE ON RUNNING AWAY, MARCH 16, 1949

Anyone who delves into China, its people and history, soon discovers that, over the years, there have been an assortment of imperfect methods used to render the nonalphabetic Chinese language into English and other romanized languages. Most systems have been phoneticthat is, words have been transliterated based on the sounds in Chinese. This is problematic since pronunciation of words can vary to the point of their being unrecognizable from one Chinese dialect to the next. My surname, Zia, for example, is a common Chinese name that was transliterated using the system dominant in early 1900s Shanghai and based on its dialect. With different romanization methods and dialects in play, the alphabetic spelling can be Hsieh, Hsia, Sieh, Sie, Jie, and more. In todays China, it would be Xie using pinyin, the official standard in China and widely accepted by most universities around the world, including in the United States.

During the period covered by this book, from the 1920s to the 1960s, various romanization systems have been in use. Furthermore, places were often renamed by the latest political or military organization in command of the oft-changing landscape. As many other authors have done, I use the most familiar names for key historic figures, particularly if their names in pinyin may confuse readers unversed in the nuances of romanization. Thus Chiang Kai-shek, Soong May-ling, and T. V. Soong appear in this book, not Jiang Jieshi, Song Meiling, or Song Ziwen, as they are in pinyin. However, I defer to pinyin where the names will not confound the reader, as with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai.

Similarly, I rely on the present-day place-names Guangzhou, Suzhou, Chongqing, and Taiwan, rather than Canton, Soochow, Chungking, and Formosa. For street names, I use the name as known by the books characters, for example, Avenue Joffre and Jessfield Road, not the current Huaihai Lu and Wanhangdu Lu. However, to make those former street names relevant to present-day Shanghai, Ive placed an endnote with the current name on the first reference to each. I also refer to Chiang Kai-sheks government as Nationalists, which is how they were commonly known in English, rather than Kuomintang (in the Wade-Giles system) or Guomindang (in pinyin).

Finally, some words appear that are peculiar to Shanghai: Expatriates called themselves Shanghailanders, a term applied only to the citys foreign residents, whereas Shanghainese refers only to its Chinese residentsa distinction that would be well appreciated if one were transported alongside the characters of this book.

SHANGHAI, MAY 4, 1949

Bing sat straight up in the pedicab, gripping the hard seat as the driver cursed and spat. She watched with alarm as his feet, clad in sandals cut from old tires, seemed to slow to a snails pace just when she most needed speed. This stylish-looking young woman had imagined that her last hours in Shanghai would be spent waving farewell from a ships deck to envious onlookers below as a river breeze gently lifted her dark hair, just as shed seen in the movies. After all, she was about to leave Chinas biggest, most glamorous, and most notorious city. Shanghai had been Bings home since she had arrived following the Japanese invasion nearly twelve years earlier, as a frightened girl of nine. But now, with the imminent threat of a violent Communist revolution, she was running away again, along with half the citys population, it seemed. And instead of standing at the rail, exchanging smiles with the ships other passengers, she was stuck in traffic, terrified that she wouldnt reach the Shanghai Hongkou Wharf in time. That would spell disaster.

She lurched forward as the pedicab driver stood on the pedals of his three-wheeled cycle and came to a stop. Around her was a sea of other pedicabs, rickshaws, cars, buses, carts, and trucksall screeching and honking, their drivers yelling every manner of obscenity. The cacophony reverberated against the walls of the stone-and-concrete canyon of Nanjing Road. Bing was no stranger to Shanghais mayhem, but she had never seen anything quite like this. Of all times to be stuck in such bedlamon the very day she had to get to the riverfront, the date set for her departure from this desperate city.

Shed sewn her floral-print