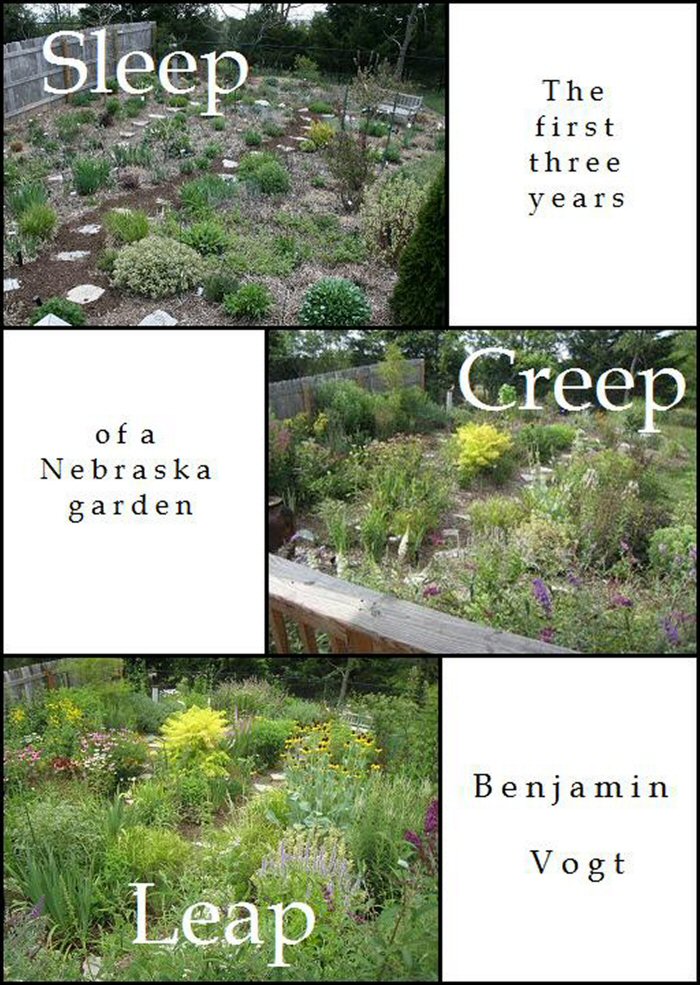

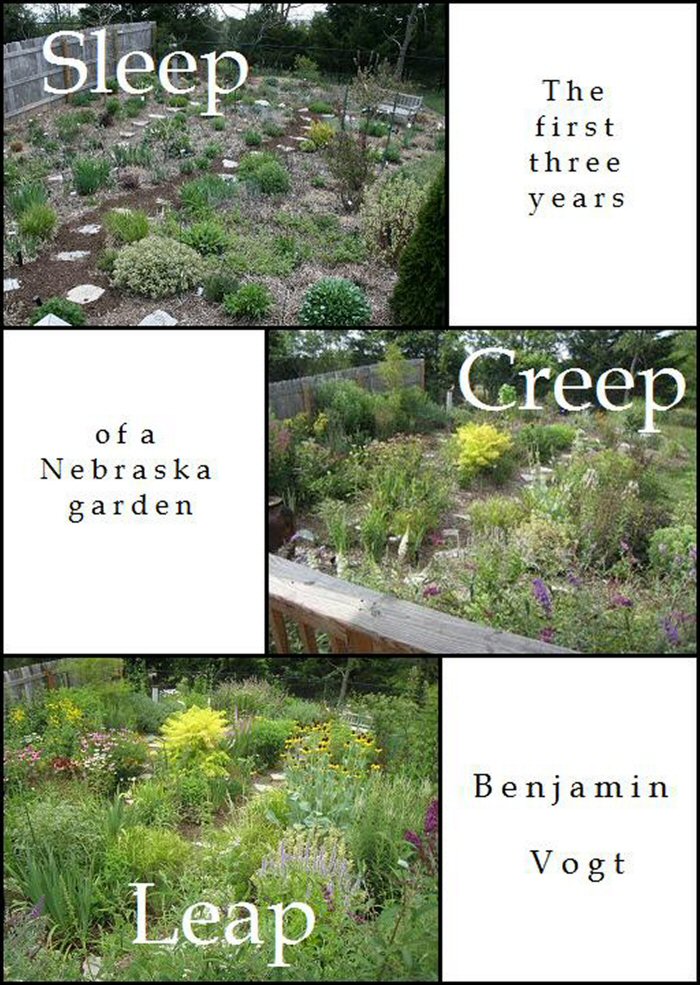

Sleep, Creep, Leap

The First Three Years of a Nebraska Garden

By Benjamin Vogt

BOOKS BY BENJAMIN VOGT

Afterimage: Poems (SFA Press)

Without Such Absence (Finishing Line Press)

Indelible Marks (Pudding House)

http://deepmiddle.blogspot.com

Sleep, Creep, Leap: The First Three Years of a Nebraska Garden

Copyright 2011 Benjamin Vogt

ISBN: 978-1-61792-834-5

Photos by Benjamin Vogt

CONTENTS

Compared to gardeners, I think it is generally agreed that others

understand very little about anything of consequence.

Henry Mitchell

2007-2008

The wonder of gardening is that one becomes a gardener by becoming a gardener.

Horticulture is sometimes described as a science, sometimes as an art, but the truth is that it is neither, although it partakes of both endeavors. It is more like falling in love, something which escapes all logic. There is a moment before one becomes a gardener, and a moment afterwith a whole lifetime to keep on becoming a gardener.

Allen Lacy

First Garden First

To be fair, this isnt my first garden. Technically. And if I really get anal about it, perhaps my first garden was a green bean plant in a Styrofoam cup growing on the window ledge of my first grade classroom. I still remember the smell of that particular soilvery sweet, like sugary cigar smoke mixed with rose petals. Something like that. I remember sticking my finger in the dirt, probing for the bean seed underneath, the feathery give of that soil, the wonderhad the seed opened yet? Was it coming toward the surface? Then the two leaves. Then four. Every morning Id check on the progress, along with my classmates, and during the day Id glance over from my desk at the small cup with my name scribbled across the front, uncomfortably angled down the curve so it looked like a crazy person wrote it.

But if one is talking about several plants in the ground, my first garden was out the front patio of my townhome when I moved to Lincoln in 2003 to begin my PhD. The covenants said I could plant things, and that was all my green thumb mother needed to hear. You need something out here, to give it some life, some character, she said standing out front after helping me move boxes in with my dad. Youll be much happier for it, she continued, her arms folded across her chest, surveying the grass and vinyl siding, then looking back over her shoulder. Trust me. Lets find a nursery.

So we borrowed my dads SUV, picked up lavender, coneflowers, coreopsis, penstemon, a butterfly bush, a rose of sharon on a stick, some arborvitae and boxwood, some plastic edging. When we came back with a full truck my dad asked if we bought the whole store. It seemed like it to me.

Though I was looking forward to the plants, to a mini garden of about thirty square feet, I didnt really understand what it meantnot to me, or my mother, who I grew up gardening with. Her garden was split in two: maybe two thousand or more square feet out back, and at least that much out front. I often went to nurseries with her early in the morning each summer, sometimes just to get out of the noisy house. I didnt know hardly anything about growing plants.

My little patio garden in Nebraska was hard work. Thick, wet clay from a sprinkler system that overwatered and made the spade weigh an extra ten pounds. A full day of ripping up grass and planting on the south side in August made me question another proposed trip to the nursery. I had two dozen plants in the ground, raised a few inches in the clay, mulched, watered in. Plants. What now? My parents left me on my own a day later.

Over the years I taught myself how to deadhead by trial and error, never once consulting the internet, and maybe just a few times my mother. Hows the garden going? Shed ask on the phone, and Id reply sheepishly, humbled by the thought that this small space might be called the G word. Going good. Everything doubled in size this year. I even saw a big yellow butterfly on the butterfly bush today. My moms voice jumped as she said, Oh, I bet thats a swallowtail. Arent they neat? And I supposed they were. Slowly, ever so slowly, I was getting into my manageable space. An hors doeuvre, in many respects. Something that I never consciously connected to my childhood or my mother, and never, until I proposed to my girlfriend and we started house hunting, something I thought of taking much further.

The last summer in the townhome I carved out another ten square feet along the sidewalk and put in some liatris, snow-in-summer, a few more coneflowers, an aster. I didnt really know what I was doing, but ripping up the sod I knew Id caught a bug. Those ten feet were a watershed moment, a dam cracking and soon to break. As I babied the new plants with topsoil and mulch, and kneeled on the hard cement pushing my finger into the sweet earthexploring their growing root zones and pulling out the smallest weedsI emerged from nearly thirty years of a blurred life I didnt recognize into a world that suddenly seemed more like home, something Id always been a part of but never really knew.

Much Mulch

Its late morning already, and weve finally made it to the new house. In two weeks well move in, married, but until thenand before the sod gets laidmy fiance and I are here to spread mulch. Twenty yards.

The sun feels as if its being reflected off of a series of mirrors, each mirror focusing the heat and light. The air is thick and its windy, carrying the musky smell of a nearby farm. I slide a wheelbarrow out of my hatchback and give my wife two bucketsshe insists that buckets will be easier.

On the east side of the house, on an empty lot, is a dump truck load of wood mulch. Three quarters of it will go behind the house, the rest out front. We dig in. I map out the edges of the garden by outlining it with wheelbarrow loads, and my wife fills in the soil one small bucket at a time. Are you sure you dont want to go buy another wheelbarrow? I ask, and she insists that itd just be too cumbersome and heavy. And she may be right.

After a few loads I see how long this will take. My wife has already retreated twice into the house to rinse out mulch dust from her contact lenses, and Im beginning to feel like a slave driver. We must establish a rhythm ingrained in me during my childhood: years of spreading hay in dirt basements each winter for my dad as he built houses, untold rooms swept as workers installed plumbing and electrical, and hours of mowing weeds on empty lotsall of these $5 per hour jobs ensured me that steady repetition was key to surviving. One must retreat deep inside ones head and make a whole comatose world out of manual labor, and to get there meant emotionless efficiency. My wife disagreed, as I stopped to encourage her with a hug as she cried out the grime and heat.

Each load I jammed in more mulch into the corners of the wheelbarrow, tempting fate and gravity. As we finished about 200 square feet we approached the soggy part of the future garden, and I laid down a mulch bridge that quickly absorbed the water. Several times I got stuck and my wife pulled the wheelbarrow as I pushed, once with the load spilling out to the side like a Sdumpr truck. Yet I kept adding mulch, even half shovel fulls, even individual pieces, anywhere I could in each load. When I went home and found mulch in my socks, pockets, and underwear, I saved them in a container to bring back.

Soon my skin color changed, from red to brown as the mulch dust glued to my sweat, perhaps having the side benefit of working as sunscreen. You want to go inside, take a drink, cool off? Id ask my wife. We could just go home, shed reply, but then refill her 10 gallon bucket and carry on.

Next page