John Bul Dau - God Grew Tired of Us

Here you can read online John Bul Dau - God Grew Tired of Us full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: National Geographic Society, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:God Grew Tired of Us

- Author:

- Publisher:National Geographic Society

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

God Grew Tired of Us: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "God Grew Tired of Us" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

God Grew Tired of Us — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "God Grew Tired of Us" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Two Lost Boys peer inside a journalists car at the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya in 2001.

First paperback printing 2008

Copyright 2007 John Bul Dau

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission is prohibited.

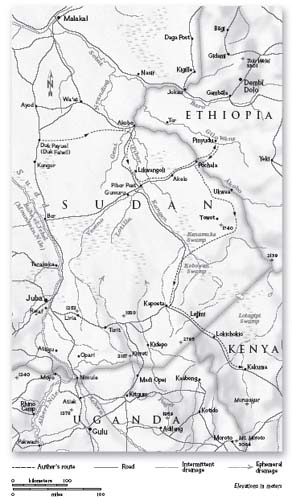

Illustration Credits Front Matter, Eli Reed/Magnum Photos; 3, Eli Reed/Magnum Photos; 6, Courtesy UNHCR; 13, Randy Olson; 18, Courtesy John Dau; 27, Malcolm Linton/Getty Images; 36, Sven Torfinn/Panos Pictures; 52, Malcolm Linton/Getty Images; 74, Derek Hudson/Sygma/Corbis; 88, Wendy Stone/Corbis; 94, Crossing the River Gilo by Mac Anyat, courtesy UNHCR. 99, Wendy Stone/Corbis; 102, Derek Hudson/Sygma/Corbis; 119, Derek Hudson/Sygma/Corbis; 132, Joachim Ladefoged/VII; 136, Derek Hudson/Sygma/Corbis; 143, Courtesy John Dau; 148, Joachim Ladefoged/VII; 166, Eli Reed/Magnum Photos; 171, Paul Daley/Newmarket Films; 182, Courtesy John Dau; 188, Eli Reed/Magnum Photos; 197, Paul Daley/Newmarket Films; 206, Courtesy John Dau; 223, Courtesy John Dau; 235, Courtesy John Dau; 241, Paul Daley/Newmarket Films; 243, Courtesy John Dau; 257, Courtesy John Dau; 263, Courtesy John Dau; 264, Courtesy John Dau; 266, Mark Mainz/Getty Images;

ISBN-13: 978-1-4262-0266-7

ISBN-10: 1-4262-0266-0

One of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations, the National Geographic Society was founded in 1888 for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge. Fulfilling this mission, the Society educates and inspires millions every day through its magazines, books, television programs, videos, maps and atlases, research grants, the National Geographic Bee, teacher workshops, and innovative classroom materials. The Society is supported through membership dues, charitable gifts, and income from the sale of its educational products. This support is vital to National Geographics mission to increase global understanding and promote conservation of our planet through exploration, research, and education.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463) or write to the following address:

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, DC 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit the Societys Web site at www.nationalgeographic.com/books

To John Garang

God made him for a great purpose: to unite and inspire the people of southern Sudan. He died too young, but his mark will never pass away. We Sudanese owe him much.

T HE NIGHT THE DJELLABAS CAME TO D UK P AYUEL , I REMEMBER that I had been feeling tense all over, as if my body were trying to tell me something. I could not sleep.

It was a dark night, with no moon to reflect off the standing water that pooled beside our huts. My parents and the other adults were sleeping outside, so the children and elderly could all be inside, away from the clouds of biting insects. My brothers and sisters and I, as well as about a dozen refugees from other villages in southern Sudan, stretched out on the ground inside a hut that had been built especially for kids. I lay in the sticky heat, tossing and turning on a dried cowhide, while others tried to sleep on mats of aguot, a hollow, grasslike plant from the wetlands that women of my Dinka tribe stitch together. Our crowded bodies seemed to form their own patchwork quilt, filling every square foot with arms and legs.

I opened my eyes and stared toward the grass ceiling and the sticks that supported it, but I could see nothing. Inside the hut it was as dark as the bottom of a well. All was silent except for the whine of the occasional mosquito that penetrated the defenses of the double door, a two-foot-high opening filled with twin plugs of grass that were designed, with obviously limited success, to keep pests outside.

Silence. It must have been around 2 a.m.

Silence.

Then, a whistle. It started low and soft at first, then grew louder as it came closer. Other whistles joined the chorus. Next came a sound like the cracking of some giant limb in the forest. Again, the same sound, louder and in short bursts. I wondered if I were dreaming. As deafening explosions made the earth vibrate beneath me and hysterical voices penetrated the walls of the hut, I realized what was happening.

My village was being shelled.

I sprang up, fully awake. In my panic, I tried to run, but the huts interior was so impenetrably black I slammed headfirst into something hard. The impact knocked me backward, and I fell onto the bodies of the other children. I could not see even the outline of the door. But I could hear the voices of my brothers and sisters, loud and crying as the shells began exploding, punctuated by the occasional burst of automatic gunfire.

Is this the end of the world? a woman screamed in panic somewhere outside the hut. There was a pause, and other voices repeated the question. I did not know the answer. Then I heard my mother calling my name. Dhieu! Dhieu! she screamed. Try as I might, I could not figure out where the voice came from. I strained to listen, but recumbent bodies had come alive all over the floor and children inside the hut started to scream, too. My mother shrieked the names of my brothers and sisters, who were in the hut with me, and cried, Mith! Mith! (Children! Children!) The village cattle joined in, mooing and urinating loudly, like a rainstorm, in their fright.

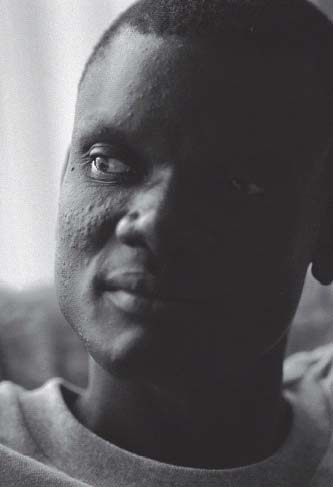

John Bul Dau contemplates a question from filmmaker Christopher Quinn during an interview at Johns Syracuse apartment.

My whole being focused on the single thought of finding the door. I scrambled around the darkened interior of the hut, bumping into a mass of suddenly upright bodies. A group of us, a tangle of arms and legs, flailed around the room, trying to find the way out. We ran into each other, and all of us fell, a jumble of bodies on the ground. The hut seemed not to have a door, and in the chaos and darkness I felt as if I were suffocating. It was a living nightmare.

Suddenly, I felt a hint of a breeze. It had to be from an opening in the exterior wall. I stumbled, let out a cry, and strained toward the puff of fresh air. I found myself on top of somebody, but I could see the doors faint outline. I crawled through the two layers of grass that formed the door of the hut and emerged into the outside world.

I stood and watched the strangely red dawn of a world gone mad. The undergrowth in our village is as thick as a curtain in the rainy season, the eight-foot-tall grasses blocking the view of the horizon. On this night, though, fires had burned away some of the brush. I could see neighbors huts normally hidden to me, ablaze like fireworks. A big luak cowshedin the distance, its squat brown, conical roof awash in crimson, resembled a miniature volcano. Shells landed in showers of dirt, smoke, and thunder. Bullets zipped through the air like angry bees, but I could not see who fired them.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «God Grew Tired of Us»

Look at similar books to God Grew Tired of Us. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book God Grew Tired of Us and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.