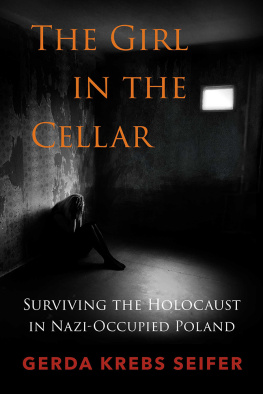

THERE IS A WATCH LYING ON THE GREEN CARPET OF THE LIVING room of my childhood. The hands seem to stand motionless at 9:10, freezing time when it happened. There would be a past only, the future uncertain, time had stopped for the present. Morning9:10. That is all I am able to grasp. The hands of the watch are cruel. Slowly they blur into its face.

I lift my eyes to the window. Everything looks unfamiliar, as in a dream. Several motorcycles roar down the street. The cyclists wear green-gray uniforms and I hear voices. First a few, and then many, shouting something that is impossible and unreal. Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler! And the watch says 9:10. I did not know then that an invisible curtain had parted and that I walked on an unseen stage to play a part in a tragedy that was to last six years.

It was September 3, 1939, Sunday morning. We had spent a sleepless night in the damp, chilly basement of our house while the shells and bombs fell. At one point in the evening when Papa, Mama, my brother Arthur, then nineteen, were huddled in bewildered silence, my cat Schmutzi began to meow outside in the garden and Arthur stepped outside to let her in. He had come back with a bullet hole in his trousers.

A bullet?

There is shooting from the roofs, the Germans are coming!

Then, in the early gray of the morning we heard the loud rumbling of enemy tanks. Our troops were retreating from the border to Krakow, where they would make their stand. Their faces were haggard, drawn, and unshaven, and in their eyes there was panic and defeat. They had seen the enemy, had tried and failed. It had all happened so fast. Two daysbefore, on Friday morning, the first of September, the drone of a great many German planes had brought most of the people of our little town into the streets. The radio was blasting the news that the Germans had crossed our frontier at Cieszyn and that we were at war! Hastily, roadblocks had been erected. Hysteria swept over the people and large numbers left town that day.

I had never seen Bielitz, my home town, frightened. It had always been so safe and secure. Nestled at the foot of the Beskide mountain range, the high peaks had seemed to shelter the gay, sparkling little town from intruders. Bielitz was charming and not without reason was it called Little Vienna. Having been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before 1919, it still retained the flavor of that era. Almost all of Bielitz inhabitants were bilingual; Polish as well as German was spoken in the stores. In the center of the city, among carefully tended flower beds, stood its small but excellent theater, and next to it the Schloss, the castle of the Sulkowskys, the nobility closely linked to the Imperial Hapsburgs.

Nothing in my lifetime had ever disturbed the tranquility of Bielitz. Only now, when I saw people deserting it, did I realize how close, dangerously close we were to the Czechoslovakian frontier; only twenty-odd miles separated us from Cieszyn.

There had been talk of war for many weeks, of course, but since mid-August our family had been preoccupied with Papas illness. Mama and I had been away in Krynica, a summer resort, from early June until the middle of August. Papa and Arthur had been unable to accompany us, and we returned when we received a telegram from Papa, suggesting we come home because of the gravity of the international situation. It had been somewhat of a shock to see how ill Papa looked when he met us at the station. His right arm was bothering him and Mama, alarmed, had called the doctor. The doctor diagnosed the illness as a mild heart attack and Papa was put to bed immediately.

The following day two specialists were summoned to Papas bedside. That same day we received a cable from Mamasbrother Leo, who was in Turkey. It read: Polands last hour has come. Dangerous for Jews to remain. Your visas waiting at Warsaw embassy. Urge you to come immediately.

Mama stuck the cable in her apron pocket, saying, Papa is ill, that is our prime concern.

Papa was to be spared excitement and worry at all costs, and visitors were cautioned not to mention the possibility of war to him. Mama little realized the fate we all might have been spared had she not concealed the truth from Papa. Yet on Friday morning, September 1, when German planes roared through the sky, Papa, who had been ill for two weeks, came face to face with reality. It was a tense day. I spent most of it in my parents bedroom and instinctively stayed close to Papa.

As that first day drew to a close, nobody touched supper, no one seemed to want to go to sleep. Mama sat in a chair near Papas bed, Arthur and I watched from the window. Horses and wagons loaded with refugees continued to roll toward the East. Here and there a rocket, like blood spouting from the wounded earth, shot into the evening sky, bathing the valley in a grotesque red. I looked at my parents. Papa appeared strange, almost lifeless. The yellow flowers on Mamas black housecoat seemed to be burning. Outside, the mountain tops were ablaze for a moment, then they resounded with a thunderous blast that made the glass in the windows rattle like teeth in a skeletons head. Everything was burning now. I looked at Mama again. Her soft, wavy, blue-black hair clung to her face. Her large, dark eyes seemed bottomless against her pale skin. Her mobile mouth was still and alien. The red glow was reflected in each of our faces. It made hers seem strange and unfamiliar. There was Mama, burning with the strange fire of destruction, and in the street the horses and wagons, the carts and bicycles were rolling toward the unknown. There was a man carrying a goat on his back, apparently the only possession he had. On the corner several mothers were clutching their infants to their breasts, and near them an old peasant woman crossed herself. It was as if the world had come to an end in that strange red light. Then, all of a sudden, Papa spoke to me.

Go, call the family and find out what they are doing.

I went downstairs. I sat down next to the phone with a long list of numbers. I started at the top and worked to the bottom, but there were no answers. The telephones kept ringing and ringing. I pictured the homes that I knew so well, and with each ring a familiar object or piece of furniture seemed to tumble to the floor.

I became panicky. It seemed as though we were alone in a world of the dead. I went back upstairs. My parents and Arthur apparently had been talking. They stopped abruptly.

Nobody answered, isnt that right? Papa asked. I could not speak. I nodded. There was no longer any pretense. Papa motioned me to sit down on his bed. He embraced me with his left arm.