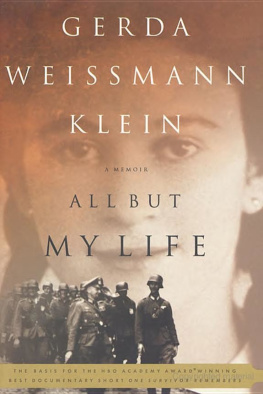

IT IS WITH TREPIDATION THAT I LOOK BACK AT WHAT I WROTE nearly a half century ago, in the springtime of my life. A welter of emotions assails me and must be sorted out. Now that I have reached autumn, perhaps I can be more objective.

I have been asked countless times, How and why did you go on during those unspeakable years? And then, How do you cope with the memory of hardships in the work camps and the pain of losing your family? I admit I no longer remember all the answers I have given, but I am sure that they often varied and depended on my mood.

The part of my formative years over which fate cast such a large shadow imposes an enormous burden and is not fully sorted out even now. No manual for survival was ever handed to me, nor were any self-help books available. Yet somehow I made my way, grappling with feelings that would let me reconcile difficult memories with hope for the future, and balancing pain with joy, death with life, loss with gain, tragedy with happiness.

Survival is both an exalted privilege and a painful burden. I shall take a few random incidents that have become important in my life and try to make some sense of them. At the same time, I realize that it is impossible to do justice to fifty years of memory. The acuteness of those recollections often penetrates the calm of my daily life, forcing me to confront painful truths but clarifying much through the very act of evocation. I have learned, for the most part, to deal with those truths, knowing well that a painful memory brought into focus by a current incident still hurts, but also that the pain will recedeas it hasand ultimately fade away.

When, in September 1946, the wheels of the plane bringing Kurt, my husband, and me from Paris and London touchedAmerican soil, he tightened his arms around me and said simply, You have come home. It has been home, better than I ever dreamed it would be. I love this country as only one who has been homeless for so long can understand. I love it with a possessive fierceness that excuses its inadequacies, because I deeply want to belong. And I am still fearful of rejection, feeling I have no right to criticize, only an obligation to help correct. I marvel at my three childrens total acceptance of their birthright and rejoice in their good fortune.

The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 helped me to become a better American. The pain and loss I experienced in Poland, the country of my birth, obliterated the nostalgic thoughts of a childhood home for which I yearn. I have found the answer to that longing in the tradition of my religion and in the land of my ancient ancestors. Israel, by extending the law of return to all Jews, has become the metaphorical sepulcher of my parents as well as my spiritual childhood home.

While my love for Israel represents my love for my parents and our shared past, the United States is my country of choice, my adult home. This country represents the love I harbor for my husband, my children, and my grandchildren. One complements the other; by being mutually supportive, they enrich and heal.

I fell in love with this country from the moment I first stepped upon its soil. It felt so right, so expansive, so free, so hospitable, and I desperately wanted to become part of the American mainstream.

I had envisioned Buffalo, which was to become my American home, as a utopian city beneath an ever-blue, brilliant sky, and had dismissed Paris, London, and New York, my way stations to this utopia. During the drive from the grand, imposing New York Central railroad station in Buffalo, I was confronted with my new citys small wooden houses, huddled together like refugees, but my disappointment lasted only a few moments. I was ready to love the city and willing to defend it, even to myself. My affection was not misplaced. Buffalo did become a true home. It nurtured me, and later my children played and laughed under rows of elm trees while I immersed myself in a new life.

In time we would move from our first apartment to another part of the city, but I would occasionally drive past the familiar location that held so much of our early memories. I would remember how it had seemed to me on my first night in Buffalo, and a picture would flash through my mind. Long after Kurt had fallen asleep, I roamed through the apartments modest rooms, stopping at the refrigerator in the tiny kitchenette that Kurts friends had amply stocked. I had always loved fruit, so I took out an apple; but before I could catch the door, it slammed shut with a bang, and terror seized me. How many years had it been since I had lived in a home where I could take whatever I wanted with impunity? It was all mine now: the apple and the refrigerator. I opened the door, fully intending to let it slam shut. Instead, I caught it in time, closed it gently, and, grateful, went to bed.

Looking up at that third-story window of our first home, I also recalled the day which catapulted me into my lifes work. I came to Buffalo in September 1946, and the following incident must have happened in late November.

I loved going to grocery stores and still do. In those days I had the handy explanation that it was a great way to learn English, since I would see pictures on labels of cans that would tell me what was insidean easy way to learn new words. The truth was different. I needed to convince myself of the abundance of available food and of its never-ending supply. I wanted the assurance of never being hungry again.

On that particular fall day, I must have dawdled in the market longer than I thought, because when I left the store, a snowstorm was gathering. I made it home, windblown, wet, and cold, and unpacked my bag on the kitchen table. Among my purchases was a loaf of bread. A whole loaf of bread, all mine! I took it into the living room and sat near the window, watching the icy gales swirling outside as I began to eat. Somehow it tasted soggy and a bit salty.

What was wrong with me? Here I was, sitting in a warm, secure place with a whole loaf of bread. Why, then, did I feel so sad, so forlorn? Slowly, the answer began to dawn. During the long years of deprivation, I had dreamed of eating my fill in awarm place, in peace, but I never thought that I would eat my bread alone. Later that evening, I told Kurt that I had been thinking of my friends still in Europe, cold and hungry. I had to do something.

Out of that need evolved my work with the local Jewish Federation, where I soon found myself putting stamps on envelopes and sealing them. I was immensely proud of having become a volunteer. When Kurts aunt cautioned me that volunteer work was really for the wealthy, I agreed wholeheartedly. I considered myself rich now.

It didnt take long before the director of the office suggested that there were other ways to help. Could I tell some of the Buffalo Jewish community what I had seen and lived through? He waved aside protestations about my halting, faulty English. It did not matter that I was not articulate; he assured me that I would somehow manage to convey my feelings. And so, in the fall of 1946, I tried to tell my story, and I have continued to do so ever since.