T ABLE OF C ONTENTS

to Emma

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

With love and thanks to my mother, Claudia, and my sister, Jemima, for their help and support. Huge thanks to everyone who gave me feedback and advice, especially Scott Bicheno, Max Schaefer, Simon Kavanagh and Oliver Cheetham.

Deep love and gratitude to Emma Bircham, again and always.

Thanks to all at Macmillan, most especially to my editor Peter Lavery for his incredible support. And infinite gratitude to Mic Cheetham, who has helped me more than I can say.

I dont have space to thank all the writers whove influenced me, but I want to mention two whose work is a constant source of inspiration and astonishment. Therefore to M. John Harrison, and to the memory of Mervyn Peake, my humble and heartfelt gratitude. I could never have written this book without them.

I even gave up, for a while, stopping by the window of the room to look out at the lights and deep, illuminated streets. Thats a form of dying, that losing contact with the city like that.

Philip K. Dick, We Can Build You

Veldt to scrub to fields to farms to these first tumbling houses that rise from the earth. It has been night for a long time. The hovels that encrust the rivers edge have grown like mushrooms around me in the dark.

We rock. We pitch in a deep current.

Behind me the man tugs uneasily at his rudder and the barge corrects. Light lurches as the lantern swings. The man is afraid of me. I lean out from the prow of the small vessel across the darkly moving water.

Over the engines oily rumble and the caresses of the river small sounds, house sounds, are building. Timbers whisper and the wind strokes thatch, walls settle and floors shift to fill space; the tens of houses have become hundreds, thousands; they spread backwards from the banks and shed light from all across the plain.

They surround me. They are growing. They are taller and fatter and noisier, their roofs are slate, their walls are strong brick.

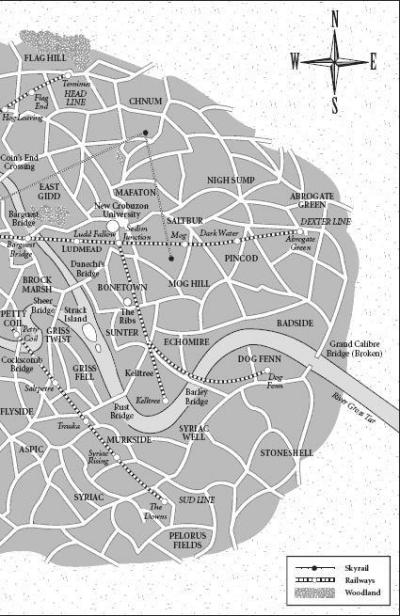

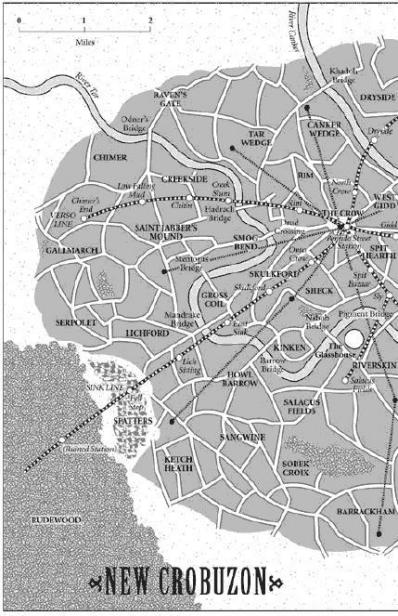

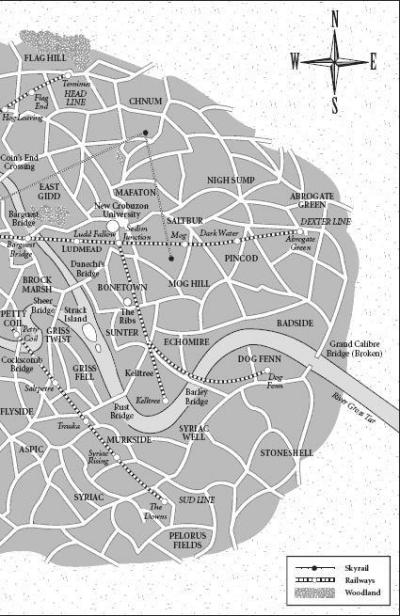

The river twists and turns to face the city. It looms suddenly, massive, stamped on the landscape. Its light wells up around the surrounds, the rock hills, like bruise-blood. Its dirty towers glow. I am debased. I am compelled to worship this extraordinary presence that has silted into existence at the conjunction of two rivers. It is a vast pollutant, a stench, a klaxon sounding. Fat chimneys retch dirt into the sky even now in the deep night. It is not the current which pulls us but the city itself, its weight sucks us in. Faint shouts, here and there the calls of beasts, the obscene clash and pounding from the factories as huge machines rut. Railways trace urban anatomy like protruding veins. Red brick and dark walls, squat churches like troglodytic things, ragged awnings flickering, cobbled mazes in the old town, culs-de-sac, sewers riddling the earth like secular sepulchres, a new landscape of wasteground, crushed stone, libraries fat with forgotten volumes, old hospitals, towerblocks, ships and metal claws that lift cargoes from the water.

How could we not see this approaching? What trick of topography is this, that lets the sprawling monster hide behind corners to leap out at the traveller?

It is too late to flee.

The man murmurs to me, tells me where we are. I do not turn to him.

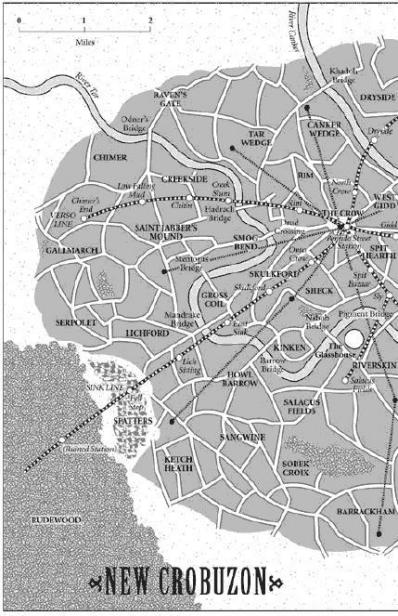

This is Ravens Gate, this brutalized warren around us. The rotting buildings lean against each other, exhausted. The river smears slime on its brick banks, city walls risen from the depths to hold the water at bay. There is a vile stink here.

(I wonder how this looks from above, no chance for the city to hide then, if you came at it on the wind you would see it from miles and miles away like a dirty smear, like a slab of carrion thronging with maggots, I should not think like this but I cannot stop now, I could ride the updrafts that the chimneys vent, sail high over the proud towers and shit on the earthbound, ride the chaos, alight where I choose, I must not think like this, I must not do this now, I must stop, not now, not this, not yet.)

Here there are houses which dribble pale mucus, an organic daubing that smears base faades and oozes from top windows. Extra storeys are rendered in the cold white muck which fills gaps between houses and dead-end alleys. The landscape is defaced with ripples as if wax has melted and set suddenly across the rooftops. Some other intelligence has made these human streets their own.

Wires are stretched tight across the river and the eaves, held fast by milky aggregates of phlegm. They hum like bass strings. Something scuttles overhead. The bargeman hawks foully into the water.

His gob dissipates. The mass of spittle-mortar above us ebbs. Narrow streets emerge.

A train whistles as it crosses the river before us on raised tracks. I look to it, to the south and the east, seeing the line of little lights rush away and be swallowed by this nightland, this behemoth that eats its citizens. We will pass the factories soon. Cranes rear from the gloom like spindly birds; here and there they move to keep the skeleton crews, the midnight crews, in their work. Chains swing deadweight like useless limbs, snapping into zombie motion where cogs engage and flywheels turn.

Fat predatory shadows prowl the sky.

There is a boom, a reverberation, as if the city has a hollow core. The black barge putters through a mass of its fellows weighed down with coke and wood and iron and steel and glass. The water here reflects the stars through a stinking rainbow of impurities, effluents and chymical slop, making it sluggish and unsettling.

(Oh, to rise above this to not smell this filth this dirt this dung to not enter the city through this latrine but I must stop, I must, I cannot go on, I must.)

The engine slows. I turn and watch the man behind me, who averts his eyes and steers, affecting to look through me. He is taking us in to dock, there behind the warehouse so engorged its contents spill out beyond the buttresses in a labyrinth of huge boxes. He picks his way between other craft. There are roofs emerging from the river. A line of sunken houses, built on the wrong side of the wall, pressed up against the bank in the water, their bituminous black bricks dripping. Disturbances beneath us. The river boils with eddies from below. Dead fish and frogs that have given up the fight to breathe in this rotting stew of detritus swirl frantic between the flat side of the barge and the concrete shore, trapped in choppy turmoil. The gap is closed. My captain leaps ashore and ties up. His relief is draining to see. He is wittering gruffly in triumph and ushering me quickly ashore and away and I alight, as slowly as if onto coals, picking my way through the rubbish and the broken glass.

He is happy with the stones I have given him. I am in Smog Bend, he tells me, and I make myself look away as he points my direction so he will not know I am lost, that I am new in the city, that I am afraid of these dark and threatening edifices of which I cannot kick free, that I am nauseous with claustrophobia and foreboding.

A little to the south two great pillars rise from the river. The gates to the Old City, once grandiose, now psoriatic and ruined. The carved histories that wound about those obelisks have been effaced by time and acid, and only roughcast spiral threads like those of old screws remain. Behind them, a low bridge (Drud Crossing, he says). I ignore the mans eager explanations and walk away through this lime-bleached zone, past yawning doors that promise the comfort of true dark and an escape from the river stench. The bargeman is just a tiny voice now and it is a small pleasure to know I will never see him again.

Next page