Published in 2017 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2017 Slavs and Tatars

The right of Slavs and Tatars to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by the editor in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 548 3

eISBN: 978 1 83860 884 2

ePDF: 978 1 83860 885 9

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card

Number: available

EDITING

Slavs and Tatars

DESIGN

Slavs and Tatars (inside: Boy Vereecken,

cover: Stan de Natris)

COPY EDITING

Kari Rittenbach

DESIGN ASSISTANT

Vincent de Jong

TRANSLATIONS (Azeri to Russian)

Farid Alakbarli

(Russian to English)

Slavs and Tatars

PHOTOGRAPHY

Aleksei Kalabin

LITHOGRAPHY

Tadeusz Mirosz

Slavs and Tatars would like to thank the Allahverdova and Safarov familie, Christoph Keller, Nic Iljine, Shirley Elghanian and Magic of Persia for supporting the first edition of the book; Evan Siegel for his help with translations, singular research into Azeri literary and intellectual history, and dedication to contemporary Iranian politics; Iradj Bagherzade, Dina Nasser-Khadivi, and Bruce Grant.

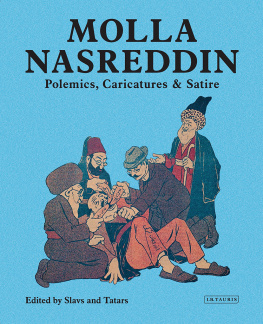

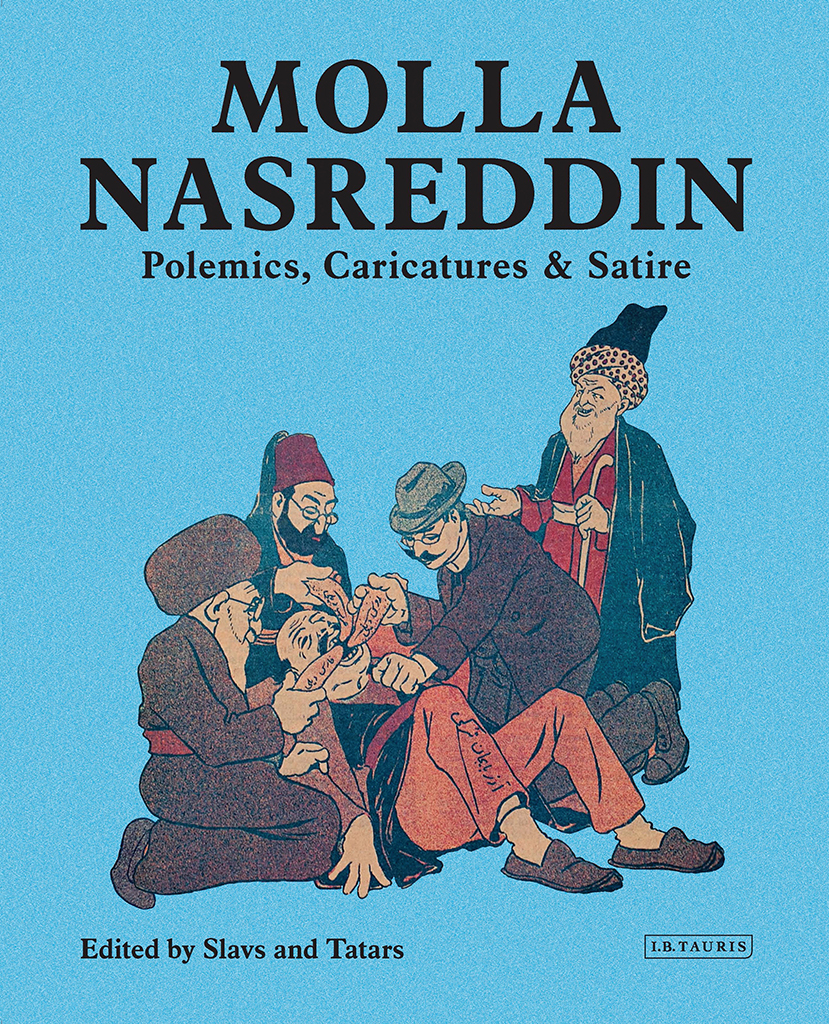

INTRODUCTION

We first came across Molla Nasreddin several years ago on a cold winter day in a second-hand bookstore near Maiden Tower in Baku. It was bibliophilia at first sight. Its size and weight, not to mention print quality and bright colour, stood out suspiciously amongst the more meek and dusty variations of Soviet brown in old man Elmans place. We stared at Molla Nasreddin and it, like an improbable beauty, winked back at us.

Published between 1906 and 1930, Molla Nasreddin was a satirical Azeri periodical edited by Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (18661932), and named after the legendary Sufi wise man-cum-fool of the Middle Ages.

Molla Nasreddin managed to do in a pre-capitalist world what todays media titans, in an uncertain, post-capitalist world, can only dream of: speak to the intelligentsia as well as the masses. Roughly half of each eight-page issue featured illustrations , which made the weekly accessible to large portions of the population who were illiterate. Tales and anecdotes of Nasreddin, the figure after whom the periodical derives its name, are told repeatedly throughout Eurasia. His reassuring character, in characteristic robe and slippers, appears on several of the weeklys covers, gesturing towards the main narrative of the illustration, with a wry smile, reminiscent of a proto-game show host or weather man. Perhaps, more importantly, the decision to publish in Azeri Turkish and not Russian as was protocol proved to be a coup: increasing the reach of the magazine beyond the urban contexts of the Russian Empire (Tbilisi, Baku) into smaller towns and provinces across the region.

ABOUT AZERBAIJAN

In the two and a half decades that transpired between the first and last issue of Molla Nasreddin, the country at the heart of the magazines polemics and caricatures Azerbaijan changed hands and names three or four times, depending on ones reading of history. Boasting a long eastern border on the Caspian Sea, situated in the southern Caucasus mountains, Azerbaijan sits squarely on the fault-line of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, with a population of some 9 million. Before 1991, however, Azerbaijan existed as an independent nation for a mere 23 months, club-sandwiched by a troika of Turks to its west, Iranians to its south and Russia to its north. Under Russian rule since the 19th century, Azerbaijan suffered much of the instability of its northern neighbour in the early 20th century the 1905 Revolution, World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 but also the short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of 19181920 as well as the Bolshevik invasion of Baku in 1921. This period of furious upheaval in the Caucasus resulted, as it did throughout the Russian Empire, in an equally frenzied creative intensity, especially in regards to the printed word.

The subject matter of Molla Nasreddin remains as relevant today as the conditions and context surrounding the publication. Debates about press freedoms continue to grip the world and the former Soviet sphere has a particularly embarrassing record of protecting the people who cover the news. MN was not an underground publication or samizdat but an official magazine, published with the license and approval of the Russian authorities. To publish such stridently anti-clerical material, in a Muslim country, in the early 20th century, was done at no small risk to the editorial team. Members of MN were often harassed, their offices attacked, and on more than one occasion, Mammadguluzadeh had to seek asylum from protestors incensed by the contents of the magazine. A century later, with Salman Rushdies Satanic Verses or the Danish cartoons of the Prophet, we have ample evidence of the dangers inherent to demonstrating the limits to freedom of speech and the collateral damage, both individual and societal, that results from it. Notwithstanding its squarely leftist leanings, Molla Nasreddin embodies, one could say, todays somewhat tired capitalist mantra that competition is good for business: satirical publications in the Muslim world abounded both before and after the weeklys appearance on the scene, especially following the Tsars decree of 17 October 1905 which allowed more press freedoms. Of note were the pan-Turkic Fyzat, the Persian-language Haqayeq, or the pro-Ottoman Taz Hayat, financed by philanthropist Zeynalabdin Taghiyev who appears in several caricatures of this volume. But none were comparable either in influence, circulation, or geographic reach to Molla Nasreddin.

Even though the publication acted as a rallying cry of sorts for the nascent Azeri nation, Molla Nasreddins non-conformism and independence were to some degree a result of the city where it was first published: Tbilisi, the present day capital of neighbouring Georgia. When Mammadguluzadeh received an official permit to publish the weekly, Tbilisi was the capital of Transcaucasia, a region whose beautifully contrived name belies its contemporary viability. Comprising present day Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, Transcaucasia was a hotbed of liberalism: from all stripes of socialists to young aristocrats la Decembrists sympathetic to their cause, narodniks, and followers of different sects. Throughout the 19th century, writers, activists, and other individuals deemed a threat to the Empire were exiled to the Caucasus, which became known as the warm Siberia. As the most cosmopolitan city of the region, Tbilisi was thoroughly polyglot, with a significant Muslim population which looked spiritually to Iran, linguistically to Turkey, and politically to Moscow. The tumult following the Russian Revolution forced