Nancy Campbell - Fifty Words for Snow

Here you can read online Nancy Campbell - Fifty Words for Snow full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Elliott and Thompson Limited, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Fifty Words for Snow

- Author:

- Publisher:Elliott and Thompson Limited

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fifty Words for Snow: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fifty Words for Snow" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Fifty Words for Snow — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Fifty Words for Snow" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I am grateful to the following individuals who generously shared with me their linguistic knowledge and their enthusiasm for snow: Theophilus Kwek (Chinese), Hanne Busck-Nielsen, Mette-Sophie D. Ambeck (Danish), Carinne Piekema, Natasha Herman and Adrian Kruit (Dutch), Mikhel and Jenny Zilmer (Estonian), Mark Olival-Bartley (Hawaiian), Matthew Teller and Marryam Reshii (Kashmiri), Anna Iltnere (Latvian), Egidija iricait (Lithuanian), Gregory Cowan (Mongolian), Marlene Creates (Newfoundland English), Imi Maufe (Norwegian), Laura Fernndez-Gonzlez (Spanish and Quechua), Elspeth Napier, Ken Cox of Glendoick Garden Centre (Tibetan), Jenny Gal Or (Tok Pisin), Ralph Kiggell (Thai), Nasim Marie Jafry (Urdu), and Phil Owen (Welsh). To these friends, and many others whose acts of kindness sustained me through a long and difficult winter, my warmest thanks.

She picks up her sharpest flint and scratches a few lines in the rock face. One strong horizontal stroke, and another below it, then four long horizontals and, getting into it now, a bit of cross-hatching to fill the space between the others. The flint arcs, almost as if her hand had slipped, and she follows that with a series of staccato chips, each powered with the same flick of her wrist she uses on her drum. Over 14,000 years and at least one ice age later, these confident lines on the wall of a Welsh cave still unmistakably show the image of a beast with magnificent antlers. When the whole worlds climate was colder, reindeer roamed across southern Europe and were known in New Mexico, according to the cave drawings left behind by Stone Age tribes and the Clovis people. The flints that drew the animals would also be turned on them.

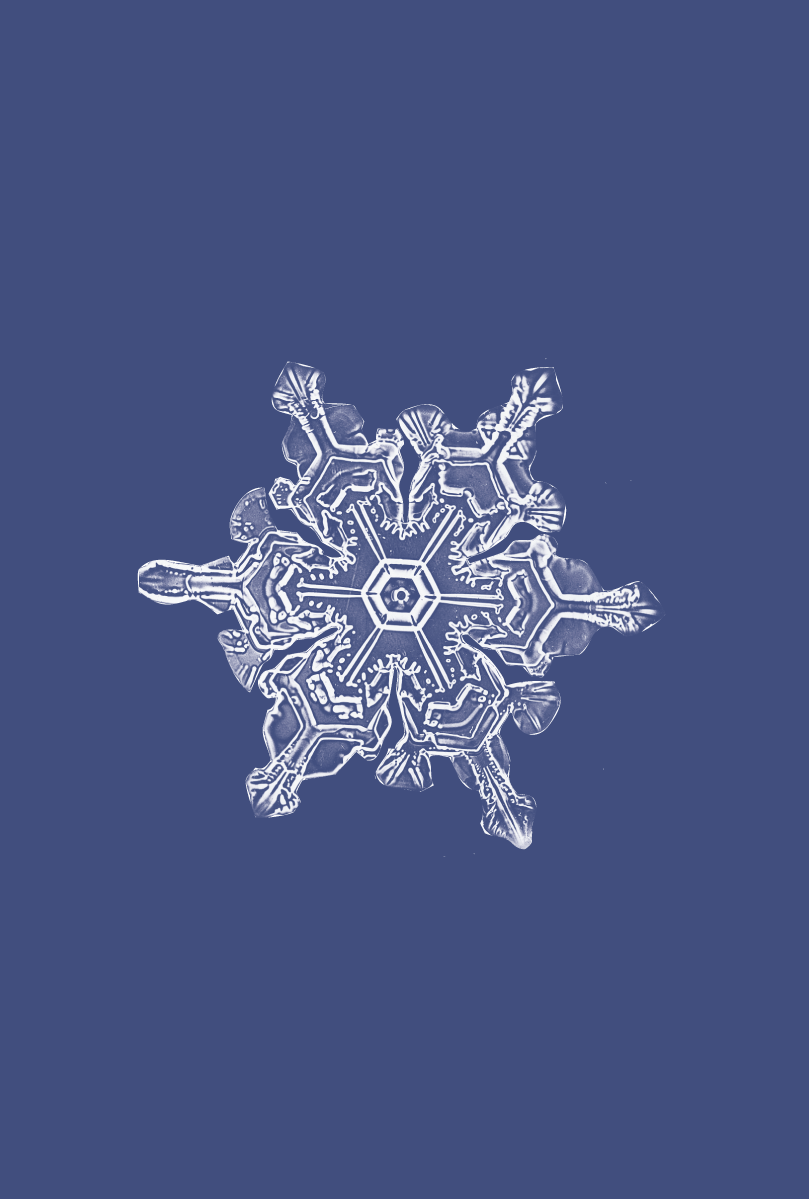

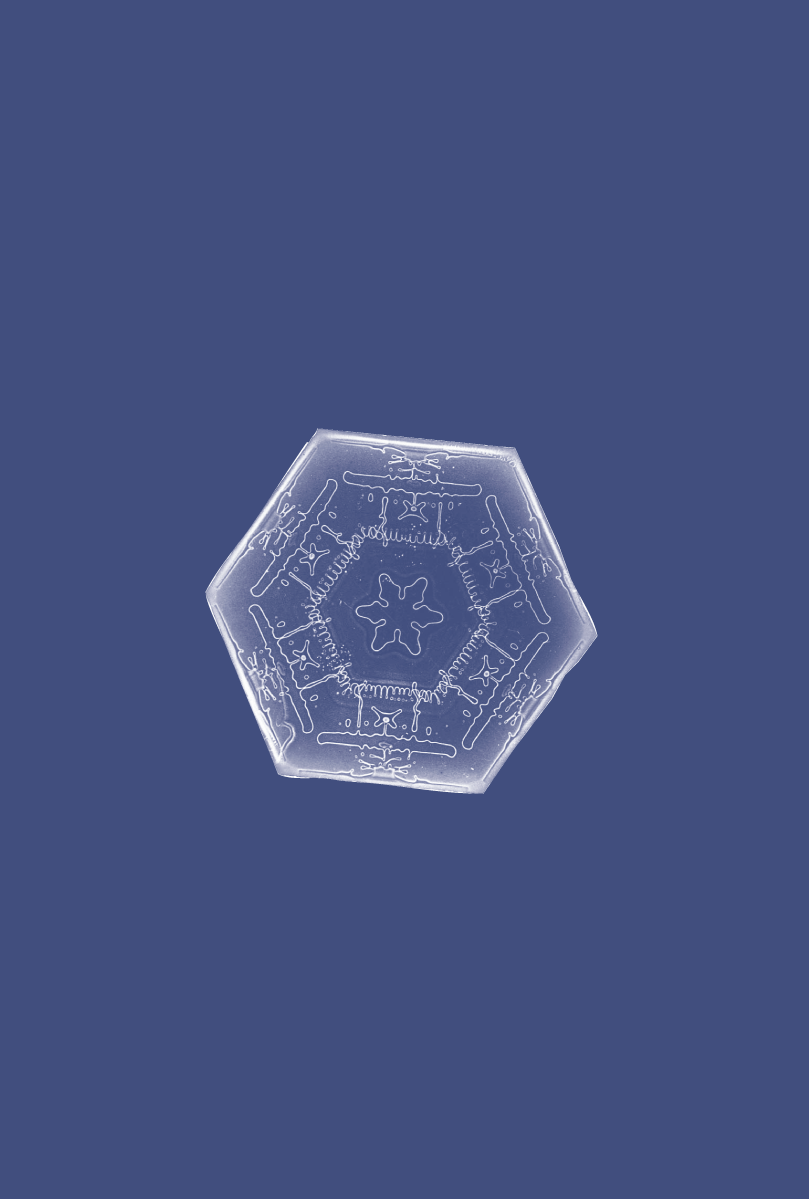

Today reindeer are creatures of the polar north, living in areas such as Guovdageaidnu in Norway, where snow covers the ground for more than half the year. All through the long winters, during which temperatures can reach as low as minus 30 Celsius, the reindeer graze on the high plateau. They dig down through the snow using their hooves or antlers to find lichens to eat. In spring, lush grasses begin to emerge from the deep snowdrifts on the coast, and it is time for the reindeer to start their great annual migration north to summer feeding grounds by the sea. They are guided by the Smi people, who have long subsisted in this harsh climate as fishers, trappers and reindeer herders. The spring weather and depth of snow decide when herders begin to move and how fast. They know that cold, crisp ground provides ideal conditions to move their animals swiftly across the plains to the coast. They will often drive the reindeer through the night, waiting for the evening frost to form a light crust on the snow, or skavvi, after the sun has thawed the surface during the day. They will rest when the afternoon sun causes soavli, or slushy snow. While they are on the move, the reindeer or at least their traces are visible on the snow, so that animals might be found again if they go wandering or join other herds.

The Smi language reflects the herders intimate relationship with their environment. The rich terminology for snow and ice includes words to describe the way snow falls, where it lies, its depth, density and temperature. One of the most significant types of snow for the Smi is sea, or loose granulated snow, which forms at the bottom of the snowpack from January to April, a little like depth hoar in the international snow classification. Snow takes on sea consistency during a cold winter, and it improves grazing conditions: it is easy for reindeer to dig through sea to the lichen growing beneath. Since sea melts rapidly, it also provides a vital clean water supply for the travellers. Its not surprising that some Smi terms for snow relate to its influence on the lives of reindeer, such as the unwelcome state of moarri, which is the kind of travel surface where frozen snow or ice breaks and cuts the legs of animals. But while there are around one hundred Smi terms for snow, the words relating to reindeer are estimated at over a thousand. And yet, to find out what the woman in the cave knew of the reindeer, we have little choice but to let the picture speak.

Taoist philosophy suggests that when theres an abundance of any natural matter, a life will come forth from it: the river will create its own fish when the water is deep enough and the forest will produce birds when the trees are dense enough. And so it follows that a woman may be generated in the heart of a snowdrift.

Nowhere in the world are the drifts as profound as in the mountains of Japan. In the remote highlands of the Japanese Alps, a series of three high mountain ranges the Hida, Kiso and Akaishi that bisect the main island of Honshu, the annual snowfall can be as great as 40 metres. The world record for the deepest snow was measured further west, on the slopes of Mount Ibuki in 1927, although it is hard to verify such records when so few of the planets snowiest peaks are equipped with snow gauges or even accessible to meteorologists and other mortals.

Yet sometimes a mysterious figure can be seen, emerging from a disorienting white-out on the Honshu hills. The yuki-onna is among a class of supernatural monsters, spirits and demons (ykai) whose alluring appearance belies their profound menace. The first yuki-onna was encountered by a poet in medieval times, her name formed from the words for snow (yuki ) and woman (onna ). Thousands of sightings have been recorded since, but one constant characteristic is a similarity to snow: her skin is cold; her hair is silver; she dresses in white. She drifts through the hills, her beauty all the more fascinating because it is so fleeting. Many tales of the yuki-onna dwell on her swift disappearance in one story she transforms into a flurry of snowflakes in a puff of wind; in another, she melts away having been persuaded by her lover to take a bath, leaving behind only a few brittle icicles floating in the water.

In these tales, the yuki-onnas desire for human lovers is usually satisfied, but her stay in the mortal world is thwarted by the folly of the people she encounters. One story, about a yuki-onna who had a relationship with a woodcutter for many years, was told to the writer Lafcadio Hearn by a neighbour in the district of Musashino. The story was published in the last of Hearns many books on Japanese culture in 1904, the year he died.

One evening, two woodcutters were coming home from the forest when they were caught in a snowstorm. The wide river they crossed daily was impassable, but luckily old Mosaku and Minokichi, his young apprentice, found shelter in a ferrymans hut. The two men slept, despite the wind blowing outside and the snow beating on the window, but Minokichi was woken in the night by a flutter of snowflakes entering the room. The door seemed to have blown open. By the snow-light (yuki-akari) he was amazed to see a woman dressed in white, bending over Mosaku and blowing upon his face her breath was like white smoke. But the old man did not stir.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Fifty Words for Snow»

Look at similar books to Fifty Words for Snow. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Fifty Words for Snow and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.