KINGDOMS

IN THE AIR

ALSO BY BOB SHACOCHIS

The Woman Who Lost Her Soul

The Immaculate Invasion

Swimming in the Volcano

Easy in the Islands

The Next New World

Domesticity

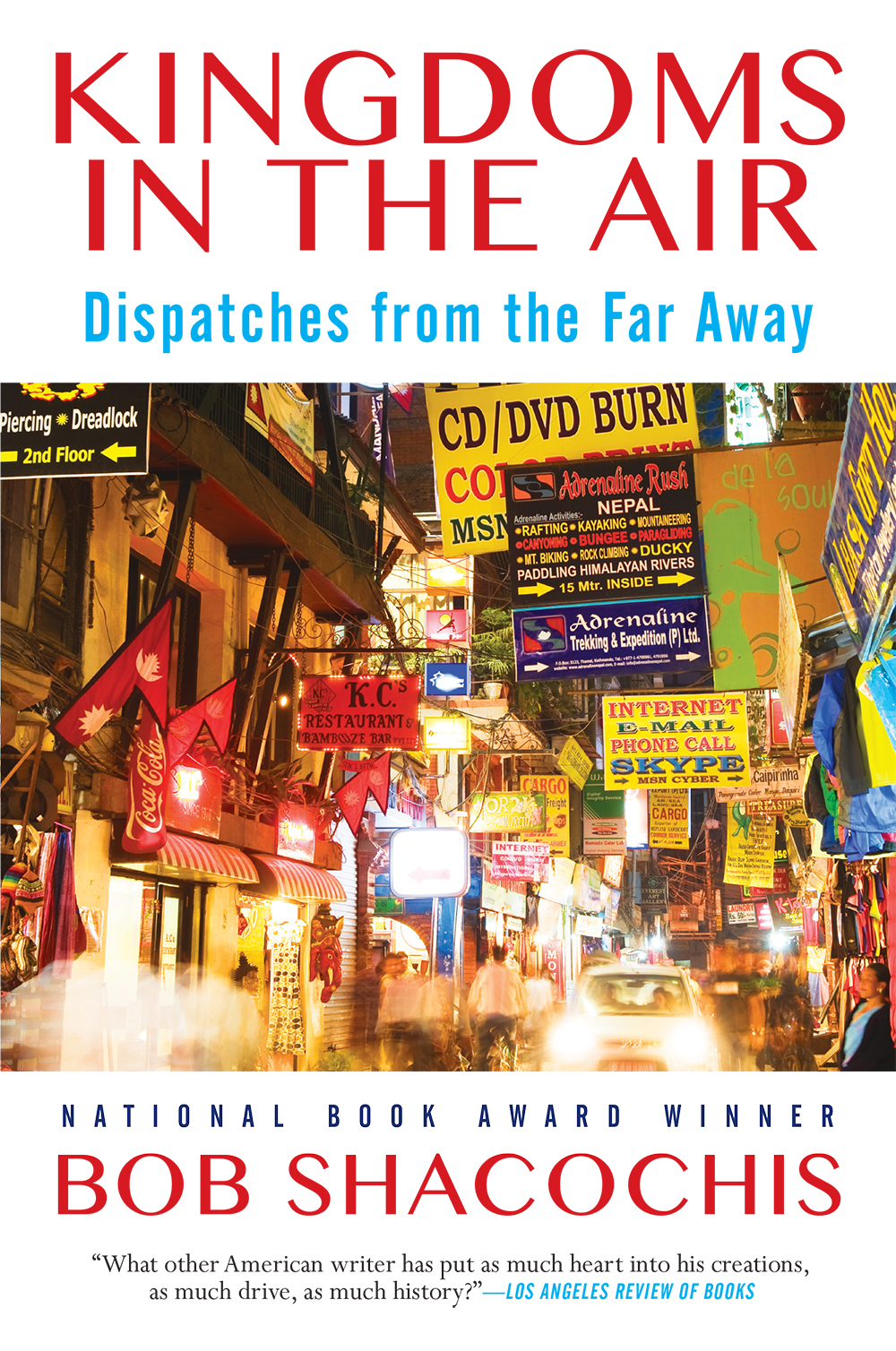

KINGDOMS

IN THE AIR

Dispatches from the Far Away

BOB SHACOCHIS

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2016 by Bob Shacochis

Versions of the long-form essays collected here were originally published in Outside , Harpers , Mens Journal , and Byliner

Jacket photograph Christian Kober/Getty Images

Author photograph Noel Pollack

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First published by Grove Atlantic, June 2016

ISBN 978-0-8021-2476-0

eISBN 978-0-8021-9022-2

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Jonah, and those who gave their hearts to Petey

CONTENTS

KINGDOMS

IN THE AIR

Kingdoms in the Air

PART ONE

Journey to the Land of Lo

(20012002)

I could now prove what had long been disbelieved, that beyond the snows of the Himalayas, hidden from the world, there truly existed a lost kingdom .

Michel Peissel, 1964

Then and Now and Then

Kathmandu, in the spring of 2001, lay dazed in its green bowl of mountains, suffering from an unusually fierce heat wave and a host of maladies of its own making, the citys pre-monsoon lethargy spiked with foreboding. Any day you expected the government to collapse under the weight of its own corruption, or the Maoists to march into the valley, or something more wicked and inconceivable to occur. Tourism was down, body counts up; a first wave of expatriates had begun to arrange its exodus. The capitals sense of dread pulsed with a surreal intensity, seemingly disconnected from the clear facts of the matter: gun battles erupting throughout the countryside, the beloved kings reluctance to deploy his army against the guerrillas, a venal ruling class of Brahmans who deserved tar and feathers, an infant democracy withering in its cradle. Like Kathmandus legendary pollution, the dread simply hung in the air; you breathed in its thick, sour pungency and exhaled one thought Something so bad is about to happen, dont even think about it and the city forged ahead on fatalism and denial, at least for a few more weeks. Then all hell exploded and has exploded without mercy ever since.

By spring 2002, after a season of bombings and midnight arrests and assassinations, Kathmandu was still reeling from the battlefront news of what had become internationally known as the killing terraces, Nepals six-year-old civil war between time-warp Maoists and the constitutional monarchy. It was an expanding catastrophe that had claimed almost four thousand lives, more than half of them since the end of last Novembers truce, when King Gyanendra, assuming the throne after the massacre of his brother King Birendra and the rest of the royal family by Crown Prince Dipendra on June 1, 2001, unleashed the Royal Nepal Army on the rebels. By summer, Gyanendra and his prime minister had dissolved parliament, the nations chief industrytourismwas crippled, and the Bush administration had braided Nepals tragedy into its all-consuming preoccupation, Americas war on terrorism, throwing money (twenty million in military aid) and personnel (Special Forces advisers) into the cauldron. By 2003, the body count had again doubled upward toward eight thousand miserable souls.

Suddenly all the arguments I have ever had or heard about the deleterious effects of trekkers on traditional cultures seemed quaint and luxurious, if not utterly frivolous. In early May 2001, I was having just such an argument with myself as I headed up to the formerly off-limits kingdom of Mustang, a semiautonomous region of Nepal, with the photographer and author Tom Laird, our wives, and three friends, to see what ten years of open doors does to an insular culture. With the jackals of war ripping Nepal apart, its tempting to look back now on that journey as a more innocent time and to think that the lessons of the journey no longer matter. But that too would be an illusion, and within the illusion, danger, and within the danger, who we are in the world.

We left Kathmandu for Pokhara on May 14, crossing paths with the Chinese prime minister at the airport, who had come to dispel any notion that China supported the Maoist insurrection in Nepal, a policy contingent upon Kathmandus reassurance that it would crack down on the countrys tenacious Free Tibet movement not just in the city but in the northern borderlands. That evening in the middle hills, strolling Pokharas lakeside strip of shops, I chatted with the vendors and entrepreneurs and was alarmed by how thorough and deep ran the popular disgust for the current situation. Restore the old monarchy, give the Maoists a chanceanything but the unruly, greed-stricken child-beast of democracy sounded good to the Nepalese.

Much had changed for the worse, little for the better in the decade since King Birendra had unlocked the doors of democratic reform in Nepal, and with them the gates of the once forbidden kingdom of Mustang. The kingdom had been loosely aligned with Nepal since the eighteenth century and formally annexed in 1946. The first outsiders had arrived only in the 1950s, Tibetan refugees with goats and yaks, and Khampa resistance fighters from eastern Tibet plotting their doomed, CIA-sponsored war against the Chinese occupation. For the next two decades, Mustang was entirely closed to foreigners, Shangri-la shuttered up tight, and only a handful of scholars eluded the ban. In 1972, the southern third of the kingdom was opened once more, and Nepals 1990 revolution pried open the rest. Upper Mustang officially opened in December 1991, and although tourist numbers were and still are restricted, close to 500 foreigners had come through by the end of 1992, a number that peaked at 1,066 in 1998. (Compare this rate with the number of trekkers visiting the nearby Annapurna Sanctuary that same year61,292.) Not surprisingly, given Nepals tourism slowdown, only 222 trekkers had registered to enter Upper Mustang by the time we arrived in 2001. If one thing terrified the Kathmandu government more than the Maoists, it was the decline of tourism, the backbone of Nepals gross national product and the only modern economic force in the feudal-like agrarian society that came close to being egalitarian. Even the Maoists knew better than to bite the hand that fed Nepal, and they enforced among themselves a strict, hearts-and-minds no-whack policy toward foreigners. French tourists wandered out of the Maoist-controlled Dolpo, in direly impoverished western Nepal, starry-eyed with tales of the wonderful guerrillas. In the governments desperation to keep hotel rooms occupied and trekking agencies booked, and to pacify its far-flung districts, which had seen their cut of the permit fee revenues, meant to be a never-initiated 60 percent, dwindle from 35 percent to 28 to 18 to 3 to nothing, the minister of tourism had recently announced the abolishment of all restricted areas but twoDolpo and Upper Mustangwithin twelve months.