All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Tim Duggan Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

T IM D UGGAN B OOKS and Crown colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

is available upon request.

PROLOGUE

I n the summer of 1984, Nasser al-Awlaki spotted a chance to take his growing family from Yemen on an extended visit to the United States, where he had spent nearly a dozen memorable years as a student and young professor. He grabbed it.

Dr. Awlaki applied for a grant from the Ford Foundation to attend a monthlong seminar at Stanford University on a cutting-edge topic, applications for the new machines called microcomputers. His years as a graduate student in New Mexico and Nebraska in the 1960s had yielded a PhD in agricultural economics and an assistant professorship in Minnesota and prepared him for a distinguished career serving his country. He would serve as Yemens agriculture minister, be named president of Sanaa University, and found another Yemeni university. Now he thought his children, especially the eldest, his thirteen-year-old son Anwar, were old enough to appreciate some of the wonders of American life.

Nasser al-Awlaki was a classic technocrat. Like generations of Muslims from the Middle East who had come to the United States for an education, he had found something morean enticing openness, freedom from the straitjackets of tradition and authoritarian government, and, of course, a taste of economic abundance. Arriving as a Fulbright scholar in 1966, he had been dispatched to Lawrence, Kansas, for English-language training and was astonished to discover that he could have all the milk he could drink at the student cafeteria. After he began his studies at New Mexico State University, his host family in Las Cruces invited him to both their churchesthe husband was Protestant and the wife Catholic. They fed him lamb and rice for Sunday dinner, figuring that menu might be familiar and comforting for a young man so far from his Arabian home.

That was my introduction to Americagood families and good people, he recalled, sitting with me in his spacious house in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, nearly half a century later.

In the late 1970s, Nasser and his wife, Saleha, had brought home to Yemen warm memories of their American years. She took pride in baking an exotic dessert she had mastered while overseas: apple pie, a recipe from her Betty Crocker cookbook. He got up early many mornings to watch the softball interviews of politicians and celebrities on Larry King Livelive in Sanaa, too, via satellite.

On their way to the Stanford computer seminar in that summer of 1984, Nasser and Saleha and their four children stopped in New York City and bought a video camera, which was quickly commandeered by Anwar, their skinny, bookish teenager. He was our cameraman for the whole trip, Nasser remembered. Anwar had been born in New Mexico when his father was a graduate student and spent his first seven years in the States, barely speaking Arabic when his parents moved the family back to Yemen. Now their oldest child proudly recorded weekend visits to Yosemite, Disneyland, and SeaWorld in San Diego. He accompanied his father to the Stanford seminar, too, growing fascinated with computers and their vast promise.

When the Awlaki family strolled the streets of Manhattan on the way west that idyllic summer, a lanky, brown-skinned young man a decade older than Anwar was walking the same crowded sidewalks. At twenty-two, Barack Obama was chafing a bit at his first postcollege job, researching and writing on business for a financial publisher and consulting firm, half-joking with his mother that he was working for the enemy. Soon he would follow his idealistic instincts to the New York Public Interest Research Group, a branch of Ralph Naders activist empire, and from there to his famous stint as a community organizer in Chicago.

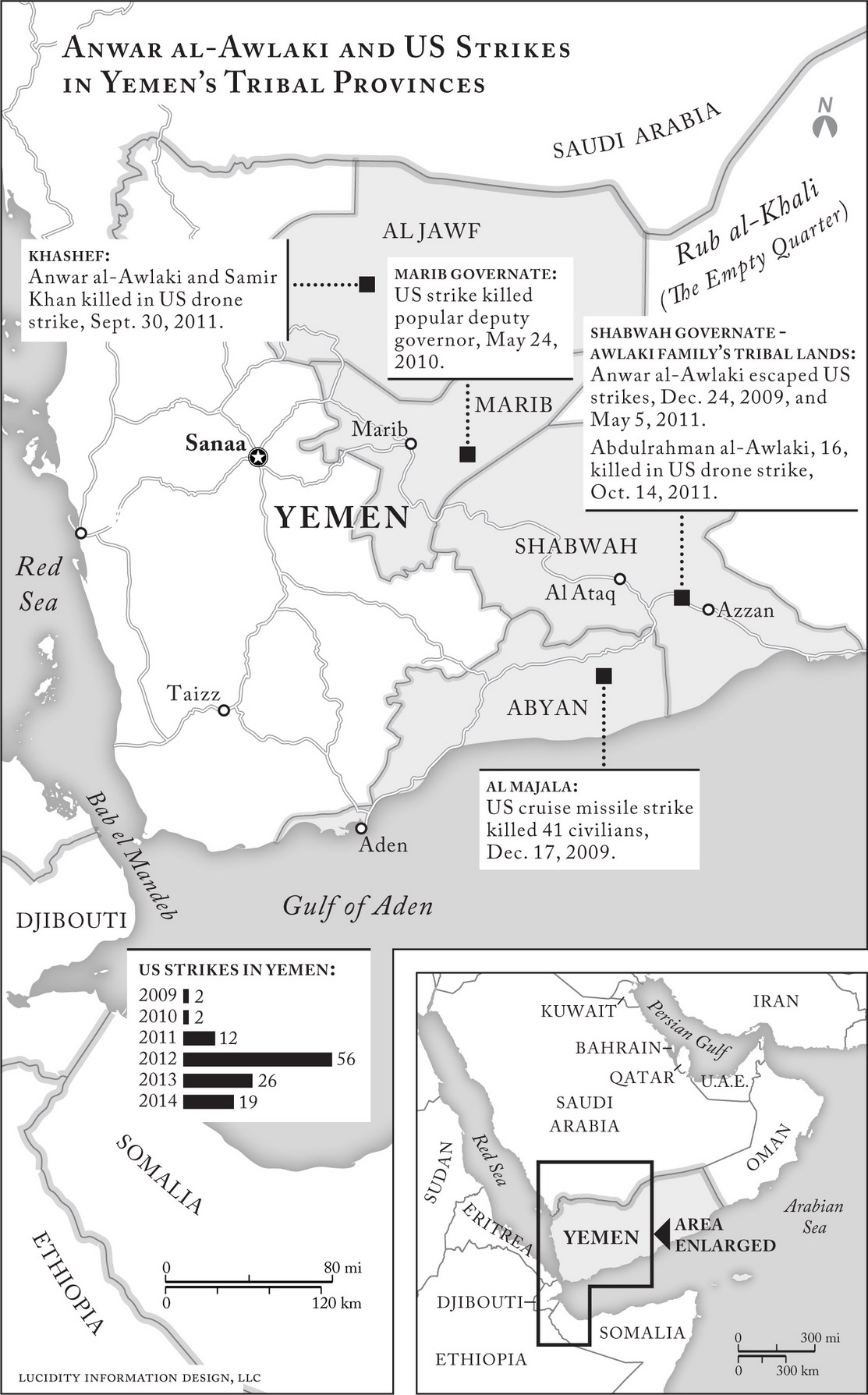

Like Anwar al-Awlaki, Barack Obama had been born in the United States to a secular-minded foreign father of Muslim background who had come on scholarship to further his education. Like young Anwar, he had left the United States as a child and lived in a Muslim country. Obama stayed in Indonesia only from ages six to ten, clearly a visitor, while Anwar al-Awlaki lived in Yemen, surrounded by extended family, from seven to nineteen. When they returned to America, their unusual backgrounds and upbringings led to struggles for both men over allegiance and identity, with radically different outcomes. Obama would embrace America and ultimately vault to the pinnacle of power, his election as president in 2008 sending a message of empowerment and possibility that resonated with millions overseas, including the Awlaki family. Awlaki would briefly sample American fame, becoming a national media star as a sensible-sounding, even eloquent cleric after 9/11 when Obama was still an unknown. Later, he would gradually and then decisively reject America and finally devote himself to its destruction. The men would never meet, except virtually, clashing in the public battleground of ideas, where the clerics mastery of the Internet would serve his jihadist cause, and violently, when Obama dispatched the drones that carried out Awlakis execution.

Awlakis death secured him a place in history: at least since the Civil War, he was the first American citizen to be hunted down and deliberately killed by his own government, on the basis of secret intelligence and without criminal charges or a chance to defend himself in court. Many Americans welcomed his demise, but its extraordinary circumstances, and the unsettling precedent it set, sparked a debate about law and principles that would go on for years.

When Nasser al-Awlaki brought his family to Ronald Reagans America, Islamic terrorism, a loaded phrase that would become a ubiquitous clich after 9/11 and that Anwar al-Awlaki would do so much to seed in the English-speaking world, was already well known. In 1983, catastrophic bombings by Iran-backed militants had hit the American embassy and Marine barracks in Beirut, killing some 258 Americans. In September 1984, shortly after the Awlakis had headed home to Yemen, the Beirut embassy annex would be attacked, with twenty-four dead. But the US homelanda word then rarely used, perhaps because for many Americans it carried an unseemly whiff of Nazismstill seemed safe from attack, protected by oceans from foreign enemies. The threat of such terrorism was distant and not so formidable. It had not yet remade the government, drained the federal budget, saturated popular culture, and overwhelmed all other associations of Islam.