Stauffer John - Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Centurys Most Photographed American

Here you can read online Stauffer John - Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Centurys Most Photographed American full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Liveright, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

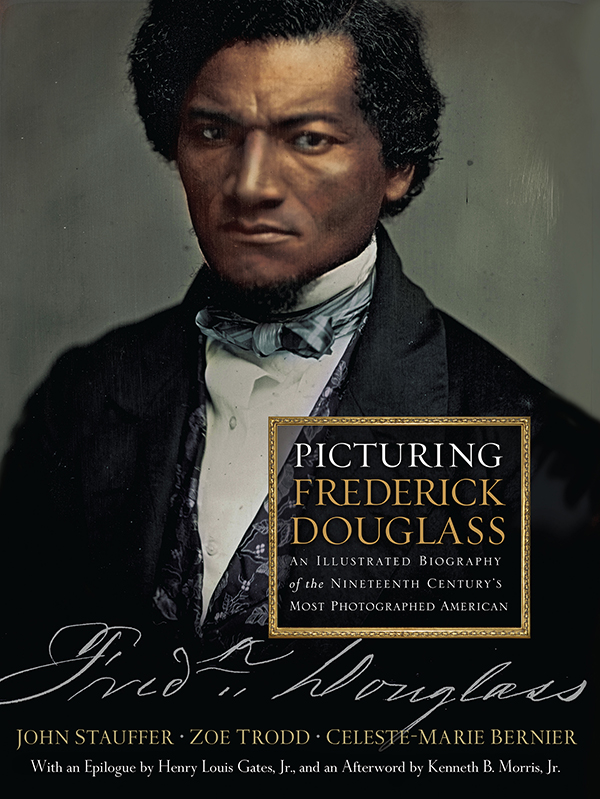

- Book:Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Centurys Most Photographed American

- Author:

- Publisher:Liveright

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Centurys Most Photographed American: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Centurys Most Photographed American" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

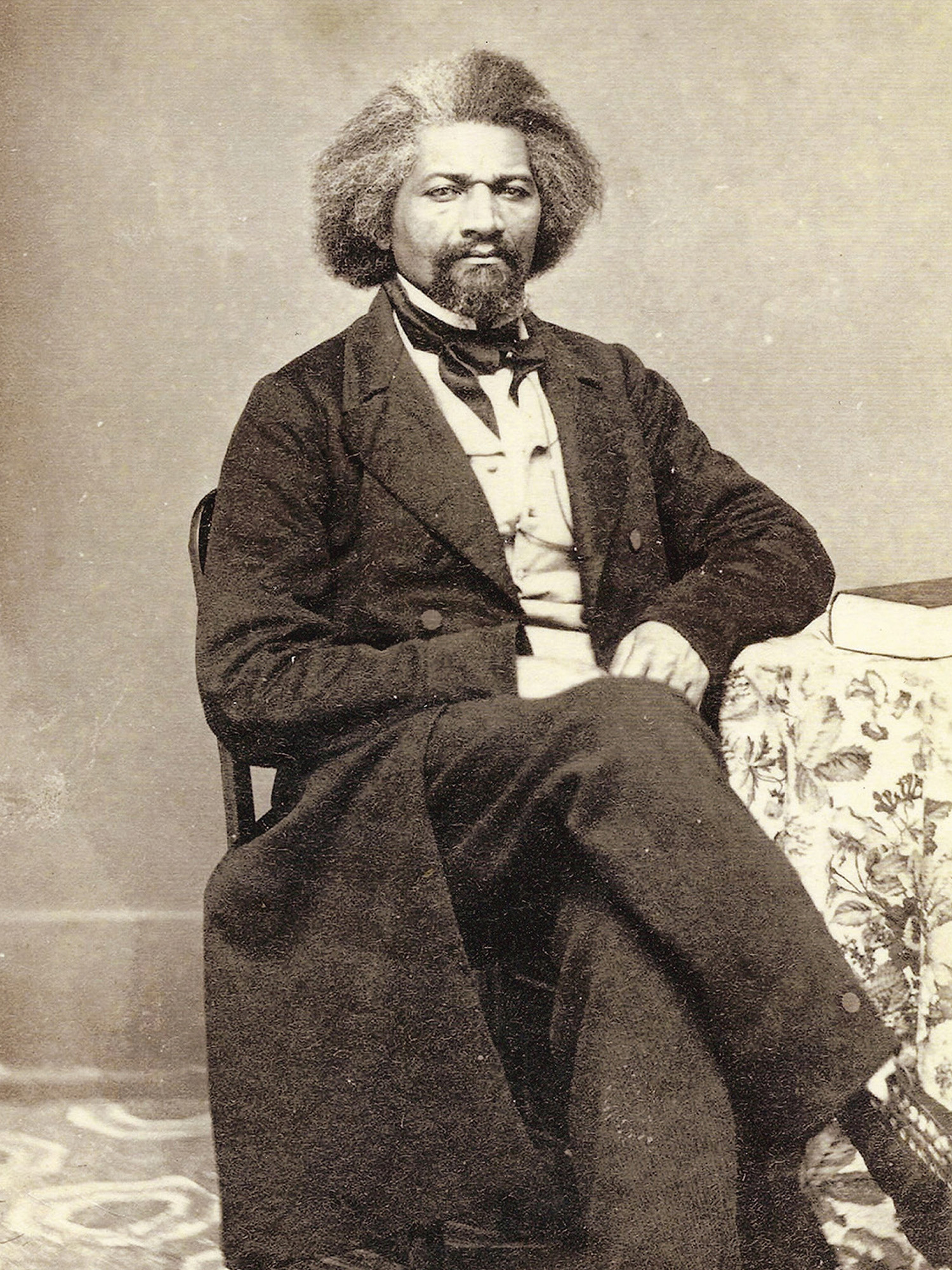

Indeed, Frederick Douglass was in love with photography. During the four years of Civil War, he wrote more extensively on the subject than any other American, even while recognizing that his audiences were riveted by the war and wanted a speech only on this mighty struggle. He frequented photographers studios regularly and sat for his portrait whenever he could. To Douglass, photography was the great democratic art that would finally assert black humanity in place of the slave thing and at the same time counter the blackface minstrelsy caricatures that had come to define the public perception of what it meant to be black. As a result, his legacy is inseparable from his portrait gallery, which contains 160 separate photographs.

At last, all of these photographs have been collected into a single volume, giving us an incomparable visual biography of a man whose prophetic vision and creative genius knew no bounds. Chronologically arranged and generously captioned, from the first picture taken in around 1841 to the last in 1895, each of the imagesmany published here for the first timeemphasizes Douglasss evolution as a man, artist, and leader. Also included are other representations of Douglass during his lifetime and aftersuch as paintings, statues, and satirical cartoonsas well as Douglasss own writings on visual aesthetics, which have never before been transcribed from his own handwritten drafts.

The comprehensive introduction by the authors, along with headnotes for each section, an essay by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and an afterword by Kenneth B. Morris, Jr.a direct Douglass descendentprovide the definitive examination of Douglasss intellectual, philosophical, and political relationships to aesthetics. Taken together, this landmark work canonizes Frederick Douglass through a form he appreciated the most: photography.

Featuring:

Contributions from Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Kenneth B. Morris, Jr. (a direct Douglass descendent)

160 separate photographs of Douglassmany of which have never been publicly seen and were long lost to history

A collection of contemporaneous artwork that shows how powerful Douglasss photographic legacy remains today, over a century after his death

All Douglasss previously unpublished writings and speeches on visual aesthetics

Stauffer John: author's other books

Who wrote Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Centurys Most Photographed American? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.