Rory Fraser - Follies

Here you can read online Rory Fraser - Follies full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Zuleika, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Follies

- Author:

- Publisher:Zuleika

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Follies: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Follies" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Follies — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Follies" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Acknowledgements

For their kindness,

patience and critical eye:

Anthony Fraser

Antonia Weir

Esm OKeeffe

Euan Monaghan

Fiona Fraser

George Tomsett

Helena Irvine

Leonie Fraser

Lucia Medina Uriarte

Marina Fraser

Ralph Wade

Theo Shack

Tom Perrin

For their generosity:

Christopher Ridgway

Clovis and Lizzie Meath Baker

Edward Peake

Hilary Peters

New College, Oxford

Nick and Georgia Coleridge

Robert and Charlotte Brudenell

Rupert Nichol

Simon Dring

The Broadway Tower Volunteers

The Duke of Beaufort

The Landmark Trust

And for their inspiration:

Beatrice Groves

Jim Sheppe

John Eidinow

Kantik Ghosh

Melanie Collins

Peter Davidson

Richard Hudson

The Schtzer-Weissmann Family

First published 2020

by Zuleika Books & Publishing

Thomas House, 84 Eccleston Square

London, SW1V 1PX

Copyright 2020 Rory Fraser

The right of Rory Fraser to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Designed by Euan Monaghan

Table of Contents

Early

Classical

Romantic

Modern

T here is something quietly exotic about Norfolk, with its blue fields of lavender whose furrows rise and fall, as though ripples across a sea of lilac, more in keeping with Provence than the East Midlands. Deep within the county, tucked between Houghton St Giles and Little Snoring, lies the sleepy village of Walsingham. This is home to the remains of Walsingham Priory, one of the most beautiful monastic ruins in England and one of our earliest follies.

Put the clock back five hundred years and Walsingham was not a quaint English village but one of the three greatest pilgrimage sites in Christendom, the centre of a cosmopolitan network that extended from Canterbury to Constantinople. It was famed for a copy of the stable where Christ was born which, according to the dubious Pynson Ballad, was described to Lady Richeldis de Faverches by the Virgin Mary via a dream vision in 1061 perhaps the first example of subcontracting by spiritual medium in England. Though its hard to imagine the three wise men, perched on top of camels, wobbling down Walsingham High Street, the difficulty of travelling to the crusade -ravaged Holy Land meant that the village became a substitute like Mini Venice in Las Vegas today. As such, Walsingham gained major celebrity, an ethereal name that echoed from every brothel in London to the Papal Court in Rome, rivalling Santiago de Compostela and even Jerusalem itself.

Driving through the countryside, I imagined the many pilgrims that had gone before me, bobbing their way through the landscape, clad in grey cloaks and broad hats, their staffs tapping rhythmically against the road; or at night, gathered around fires to ward off wild boar and wolves, checking their progress by the stars which, according to legend, were said to lead to Walsingham. When close, this group would have reached the Slipper Chapel, a sacred boundary that marks the start of the Holy Mile to the Priory, which pilgrims typically walked barefoot.

I chose to follow in their footsteps. Hobbling along the hedgerows, I tried to imagine the sort of company that I would have had. Contrary to popular belief, most of these figures were not humourless zealots but ordinary men and women for whom it was the closest thing to a holiday or, for the younger pilgrims, a dating app that medieval society allowed.

In the General Prologue to Chaucers Canterbury Tales , we are given a wonderful sense of these more human figures. On approach, we might first have heard the Wife of Bath, a large widow, well wimpled and slightly deaf, wittering about her various husbands, accompanied by the prim Prioress, Madame Eglantine and a Knight, haggard from his most recent crusade. Close by, no doubt, would have been the social climbing Friar, Hubert, audibly berating the Monk who openly admits to having no interest in religion at all and much prefers hunting. Straggling at the back is the motley Ploughman whose conversation fairly dung specific is evenly matched by the Miller, who has a fondness for breaking down doors with his head, as well as the Cook, who has an unfortunate boil which puts everyone off their food. Jangling between them all, meanwhile, is the Pardoner by far the least popular member of the group loaded with all manner of pig bones and rags, which he attempts to pass off as relics.

I continued walking until the road funneled between two high flint walls, before spilling out into the village square. This must have presented an awesome site, its cobbles clattering with wealthy merchants up from London, cross-eyed clerics from monasteries in darkest fen, mysterious figures, smelling of cinnamon, fresh from the great ports at Antwerp, Le Havre, Cadiz or, better still, the crimson flash of a cardinal and glittering train of a king. For Walsingham was visited by every monarch from Henry III to Henry VIII. Given the efficiency with which the latter managed to destroy most monastic buildings in the Reformation, I was curious as to what remained.

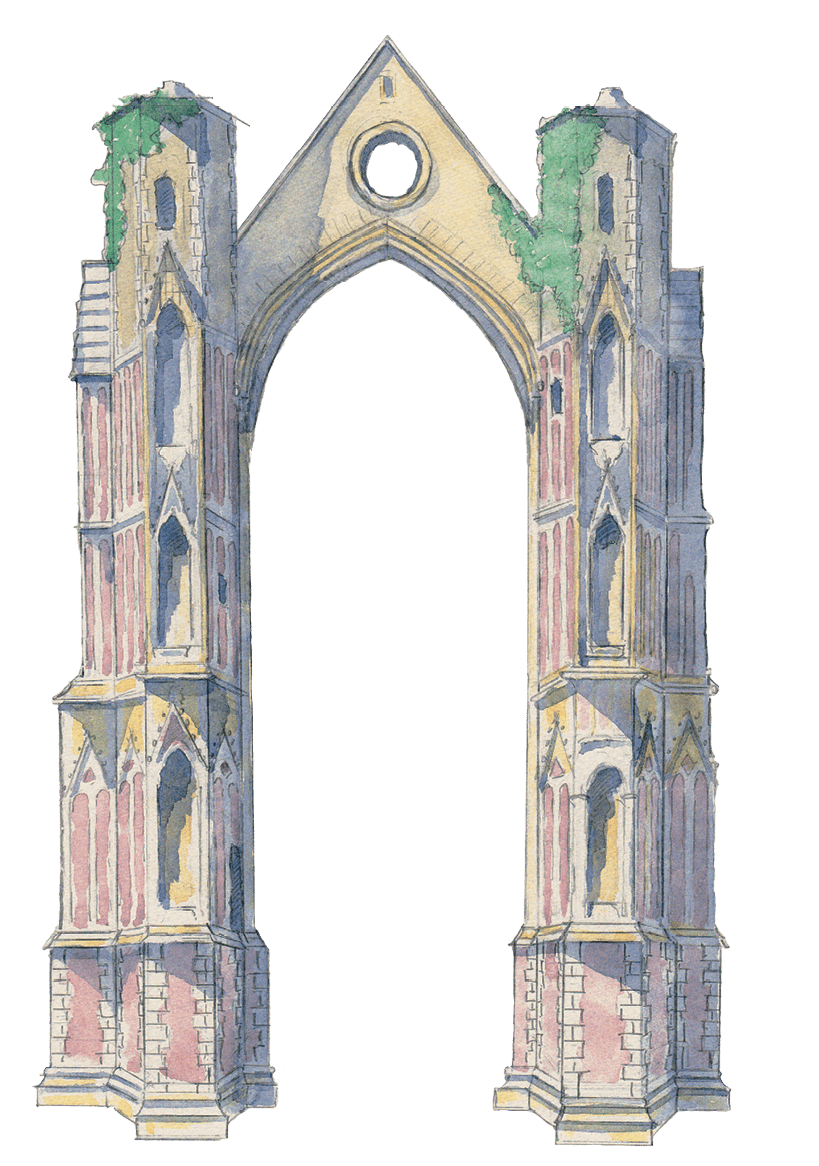

After winding along a path overhung with yew I came out onto a great pool of lawn. In the centre of this is not the usual tattered remains of a cloister, or gaunt skeleton of a nave, but instead what looks like a doorway fit for giants: a magnificent arch soaring high above the tree line, its sheer size rendering everything around it, including the handsome Palladian house that has grown from its ruins, utterly insignificant. For a moment, I was silenced. Whilst most medieval enthusiasts harp on about the majesty of Fountains Abbey or scale of Rievaulx also incorporated into landscape gardens there is something deeply magnetising about this ruin. Its lack of context and warm, pinkish glow make it all the more mysterious.

On closer inspection, it transpires that this is the remains of the East Window of the Priory which, judging by the size of the arch, must have been substantial. Though hardly any of the Priory remains, the detailing around the arch more than suffices: a patchwork of cusped windows and quatrefoils traced in flint, out of which jut stone niches from which an army of saints once peered. Around this are scattered a number of tiny doors and arrow-slit windows, hinting at the hidden corridors within as though the statues are merely hiding. All of this feeds, however, into the remains of the East Window which hangs, floating in the air, like the strands of a once intricate cobweb.

It is this window that captivates. Like a great portal, it draws the eye in, murmuring of the world that once existed behind its polychromatic scheme: of black canons who, with their white habits and cloaks, led the press of peares and palmers that thronged through the Priorys mighty doors, chanting the sweetest himnes that rose above the veil of incense and up into its gleaming towers whose golden, glittering tops / Pearsed once to the sky. All of this to see the shrine of Our Lady, an inner sanctum described by a young Erasmus, visiting from Cambridge, as a tiny wooden chapel, dark but for the tapers which glowed inside, revealing a sete mete for sayntes wt gold, syluer, and precious stones leading to a relic: the heuenly mylke of Our Lady closyd in crystalle mylkyd more than a thowsand and fyue hundrithe yere agone.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Follies»

Look at similar books to Follies. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Follies and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.