The Hidden Life of Deer

Lessons from the Natural World

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

This book is dedicated to my granddaughters, Zo, Ariel, and Margaret; to my grandsons, David and Jasper; and to my great-grandson, Jacoby. I may have other great-grandchildren in time, and this book is dedicated to them too, but I cannot name them here because they have yet to be born. May the natural world in all its present wonder be there for them and for all children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Camping Alone

My friend Antler spends weeks alone in the wilderness every fall.

I have never spent any time camping alone, maybe two or three nights

once when I got lost

and after wandering around the woods for two hours in the dark

I just lay down and slept in the leaves.

Antler talks about having to get used to walking on two legs again

when he returns.

He says that every year he leaves a little more of himself in the woods,

and that someday there will be more of him out there than here

I think it may already have happened.

Someday, maybeIll go to some lonely spot and pitch my tent

and spend my days doing what one does when alone in the woods

and sleep night after night under the ten thousand stars.

But not in winter. Another guy disappeared in the Adirondacks last week

it happens every year or two.

But not before he froze to death.

Solitary heart attack while temperature, snow, and night were falling.

Howard Nelson

Contents

Preface

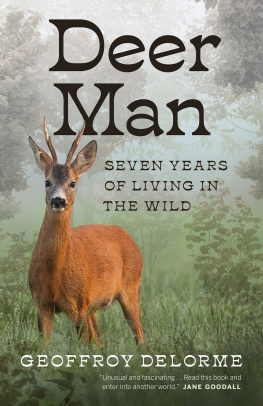

The notion to write this book came from feeding corn to deer in the winter in south-central New Hampshire. I didnt know much about them except that they seemed to like corn. I wanted to know more. But they all looked alike and they wouldnt stand still, so it took a while to fathom their behavior and really see them. I have a friend, Katy Payne, who studies elephants. It was she who discovered that elephants make infrasound, at a time when such a thing seemed impossible and no other land mammals were known to do so. Katy once told me that her advice to students who are eager to join her research team is to start by studying deer. Deer are within a mile of almost everybody, and from them one can gain an understanding of what its like to try to learn from wildlife. I thought of that as I watched my deer. For a while I studied wild elephants with Katy and was awed by her ability to recognize individuals. I could do that too, if not as well, but while I was trying to identify deer, it certainly seemed that elephants were easier.

I wished that Katy could see my deer. If anyone could sort them out, she could. I started to write her a letter to describe what they were doing. Soon the letter was many pages long and I saw it was a book, this book. So I continued with what seemed to me like research, and began to realize something that I certainly should have known already, that as members of the enormous deer family with its forty-odd species, whitetails were not unlike the other deer all over the worldmule deer of the West and Southwest, red deer or elk of the Holarctic, also India, Sri Lanka, and Burma, and reindeer or caribou of the far north, to say nothing of moose, the biggest of the deer, and all the different kinds of little deer in thickets and marshes from China to Argentina. I entered a realm full of cooperation, hierarchy, and a clear set of rules. Some of these rules are specific to whitetails, but many are fundamental to all groups, not only to the deer but also to all other creatures, which would include, of course, ourselves.

When I was a child, my father told me the chemical formulas for hemoglobin and chlorophyll, the substance in plants that makes them green and enables them to take in carbon dioxide and release our all-important oxygen. I remember the formulas to this day because they were almost identicalC55H72FeN4O6 was hemoglobin, he told me, and C55H72MgN4O6 was chlorophyll. Both had the same amounts of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen, and only one difference: right in the middle where hemoglobin has iron, chlorophyll has magnesium.

Oh wow! Young as I was, that seemed important. That a plant and a person shared something so basic seemed awesome. That plants made the oxygen in every breath we drew also seemed awesome. It gave a sense of the oneness of things. It also gave a sense of what Nature had been able to do with that formulamaking so many kinds of animals and plants, all of them different. At least to me, it gave a sense of our place on the planet. I saw that animals were important. I saw that plants were even more important. I was also to learn that compared to many of the other species, we werent important at all except for the damage we do. We do not rule the natural world, despite our conspicuous position in it. On the contrary, it is our lifeline, and we do well to try to understand its rules.

It is also full of wonder, and its right outside your door, perhaps even inside your house, even if you live in the city. You may be thinking that Im just talking about mice and rats. And yes, I would include mice and rats. In fact, were related to them via our common ancestor in the Cretaceous. They live by the rules of the natural world no matter how much we discourage them, and they do so very successfully. Our species has also been very successful. The ancestral stem must have been strong.

If we can forget our preconceptions and start fresh, observing any resident of the natural world as carefully as we can, trying to figure out what its doing and why, we will see things we otherwise could not imagine. We can enter a world as different from ours as its possible to be, the world to which we once belonged, a world we normally dont notice but which is all around us. We cant readily observe the burrowing insects in the soil, for instance, essential as they are to our well-being, and watching a plant until it does something perceptible can take a really long time, but we can easily observe many kinds of animals, especially birds and mammals who, because they are in ways so like ourselves, have much to show us.

Chapter One

It began with a bird feeder by the kitchen door. The chickadees chose only the sunflower hearts and threw all other seeds to the ground where three gray squirrels and a red squirrel ate them. One day the seeds were discovered by a passing flock of nine or ten wild turkeys. My husband and I were thrilled to see wild turkeys near the house. I put out a little corn for them. Soon, a flock of twenty-eight turkeys came for the corn. What should I have done? Refused to feed the others? I fed the others. By the end of that winter I was feeding fifty-three turkeys.

We rarely saw the turkeys in the summer. They were finding food in the woods and also in our field, where long grass hid them. But they came to our house again in the fall, just the small, original flock at first, then other flocks, every morning just before dawn. Their calls would wake me, and I would bring out a pail of corn. My presence would scare them, and they would fly away. This was distressing. It takes energy to launch a bird the size of a turkey, and more energy if she must leap straight up into the air without first running a little way to gain momentum. The corn I offered was wasted if the turkeys had to spend their calories in unnecessary flying. I began putting the corn out at night, so it would be ready for them in the morning.

One dark night after the first snowfall, I went out wearing a white bathrobe. I had no reason to make noise and therefore went quietly, and to my surprise I found myself right next to three deer. Because I was in white against the white snow, they didnt pay much attention at first, and then moved off without panic, so I distributed the corn I was carrying and went back for more. After that the deer came often. Never again did they let me near them, but I watched them from the window after the moonlight returned.

Next page