EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW ABOUT

FREE AND DISCOUNTED EBOOKS

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY!

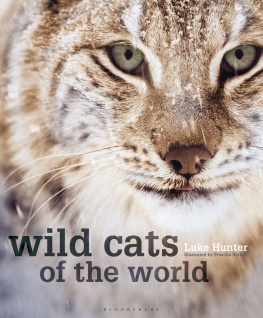

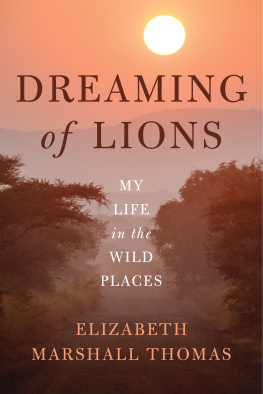

The Tribe of Tiger

Cats and Their Culture

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

For Stephanie, for Ramsay

About the Title

The title of this book is from a poem called Rejoice in the Lamb, written sometime between 1756 and 1763 by the English poet Christopher Smart. The poem is long and rambling to the point of incoherence, a product of the confusion the poet experienced and for which he was kept in solitary confinement in a madhouse. A more frightful setting than a rat-infested madhouse of the eighteenth century would be hard to imagine, as would the loneliness and despair that Smart must have known during his eight-year ordeal. His torment was mitigated, however, by the presence of a cat, Jeoffry, who became the subject of one section of the poemsome seventy-five radiant lines that are today well known and much beloved by cat fanciers and that often appear as a poem in their own right, usually under such titles as Of His Cat, Jeoffry or Jeoffry or For Jeoffry, His Cat. The rest of the poem is virtually lost, known only to a handful of scholars of English literature.

My book is but one of dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of books about cats that take their titles from Jeoffry. Almost anyone who reads the fragment, even those who are unaware of Smarts confinement and suffering, can share the strength of his feeling. In the following lines, for example, one feels the poets prayerful gratitude for Jeoffrys company in the echoing asylum during the black, terrifying hours of night:

For I will consider my cat, Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God, duly and dailyserving him.

For he keeps the Lords watch in the night against theadversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skinand glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking aboutthe life.

One feels how the cat touched the poets heart:

For having considered God and himself, he will consider hisneighbor.

For if he meets another cat he will kiss her in kindness.

For when he takes his prey he plays with it to give it a chance.

For one mouse in seven escapes by his dallying.

And one feels the poets inspiration:

For he is of the Tribe of Tiger

For the Cherub Cat is a term of the Angel Tiger.

I chose to take a title from the poem mainly because it represents a powerful link between a person and an animal, and also because the poem expresses the sanctity of an animal who the poet feels is serving God by his wholesome behavior and is keeping the devil at bay. I also chose the poem for its excellent and touching insights, made centuries before anyone thought that animals were deserving of good observation. To call the light brushing of noses between two cats a kiss, for instance, is to describe perfectly the greeting of cats who know each other (suggesting, incidentally, that there may have been a cat population as well as a rodent population in the asylum) while the observation that Jeoffry lost one mouse in seven because he played with his prey is worthy of a modern field biologist. But most of all, I chose the poem because it expresses something that is intensely true of and important about catsthat their tribe is the tribe of tigers. As the cherub is to the angel, so the cat is to the tiger, and although today we tend to put the relationship the other way around, saying that tigers are a kind of cat rather than that cats are a kind of tiger, the fact is that cats and tigers do represent the two extremes of one family, the alpha and omega of their kind.

Introduction

One summer evening at our home in New Hampshire, my husband and I were startled to see two deer bolt from the woods into our field. No sooner had they cleared the thickets than they stopped, turned around, and, with their white tails high in warning, looked back at something close to the ground as if whatever frightened them also puzzled them. We were wondering aloud what might be threatening the deer when to our astonishment our own cat sprang from the bushes in full charge, ears up, tail high, arms reaching, claws out. The deer fled, and the cat, who fell to earth disappointed, watched them out of sight.

Our cat is a male and at the time was just two years old. He weighed seven pounds and stood eight inches at the shoulder, in contrast to his two intended victims, who weighed more than a hundred pounds apiece and stood three feet at the shoulder. Even so, the difference in size and the difficulty of the task seemed to mean nothing to our cat. We realized we hadnt known him.

In truth, most of us dont know our cats. Hunting, if we stop to think of it, should of necessity be topmost in their minds. Not that the obsession always shows for what it issometimes its manifestation is obscure. As an adolescent, this particular cat, for instance, became enormously excited by a winter storm. Eyes blazing, he tore around in circles through the whirling snow, leaping high to catch the flying leaves that the wind was ripping from the oak trees. In addition, he forcefully tackles just about everything that comes his way, including a large loaf of Italian bread my husband had removed from a shopping bag and placed on the kitchen counter. To our amazement, the cat came hurtling up from the floor, landed on top of the loaf, bestrode its back with his claws dug deep into its sides, and instantly delivered what should have been a killing bite to the nape of its neck on the left side. When the loaf took no notice, the cat swarmed all over it, slashing at it with his claws and biting it deeply all over its body. Still the loaf ignored him. Suddenly the cat stopped short, stared down at his prone quarry, and then, perhaps reasoning that the loaf was dead after all, quickly scratched around it as if covering it with leaves, as wild cats hide the uneaten portions of large victims from competitors.

But there were neither leaves nor competitors in the kitchen. Abandoning the idea, the cat turned back to the loaf and rubbed it twice with his lips, swiping first to the left and then to the right. Then he jumped down from the counter and without a trace of confusion or embarrassment strolled from the room, head and tail high. Later, I photographed the badly mauled loaf of bread with the killing bite still showing on the napethe very place, according to field studies, where most man-eating tigers, such as those of the Sundarbans in the Ganges Delta, seize their victims.

The cat has a tigers name, Rajah (in just about every collection of zoo or circus tigers, one is named Rajah), and formerly had been called Rajah Tory Peterson because of his interest in birds. But after he proved himself willing to hunt everything from deer to loaves of bread, we dropped the surnames. Later it became clear that Rajah was not the only cat in our community to hunt so ardentlynot five miles from our home live other cats who also hunt deer, and have done so long enough that the resident deer have lost all fear of them. At the sight of little cats staring up at them from the long grass the deer whistle and stamp their feet in angry warning, but to no avail. The moment they lower their heads to eat, the determined cats creep nearer.

Next page