S ECOND V INTAGE B OOKS E DITION , S EPTEMBER 1989

Copyright 1958, 1959, 1989 by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

Copyright renewed 1986 by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in different form, by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. in 1959.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thomas, Elizabeth Marshall, 1931

The harmless people / by Elizabeth Marshall

Thomas.Rev., with

a new epilogue, 2nd Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-77295-4

1. San (African people) I. Title.

DT764.B8T4 1989

968.83004961dc20 89-40157

v3.1

To Stephen

CONTENTS

NOTE

The spelling of Bushman words and names is at best a rough approximation. Most Bushman words and names have clicks in them, usually clicks acting as consonant sounds. For the purpose of simplicity, the clicks have been omitted.

CHAPTER ONE

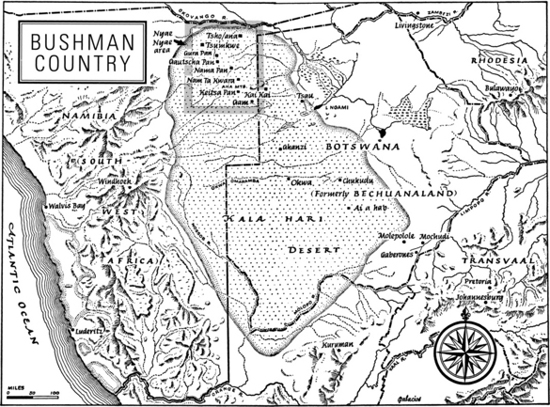

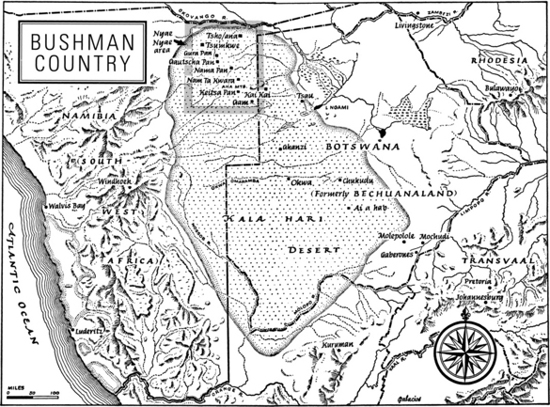

The Desert

THERE IS A vast sweep of dry bush desert lying in South-West Africa and western Bechuanaland, bordered in the north by Lake Ngami and the Okovango River, in the south by the Orange River, and in the west by the Damera Hills. It is the Kalahari Desert, part of a great inland table of southern Africa that slopes west toward the sea, all low sand dunes and great plains, flat, dry, and rolling one upon the other for thousands of miles, a hostile country of thirst and heat and thorns where the grass is harsh and often barbed and the stones hide scorpions.

From March to December, in the long drought of the year, the sun bakes the desert to powdery dry leaves and dust. There are no surface waters at all, no clouds for coolness, no tall trees for shade, but only low bushes and grass tufts; and among the grass tufts grow brown thistles, briers, the dry stalks of spiny weeds, all tangled into knots during the rains, now dry, tumbled, and dead.

The Kalahari would be very barren, very devoid of landmarks, if it were not for the baobab trees, and even these grow far from each other, some areas having none. But where there is one, it is the biggest thing in all the landscape, dominating all the veld, more impressive than any mountain. It can be as much as two hundred feet high and thirty feet in diameter. It has great, thick branches that sprout haphazardly from the sides of the trunk and reach like stretching arms into the sky. The bark is thin and smooth and rather pink, and sags in folds toward the base of the tree like the skin on an elephants leg, which is why a baobab is sometimes called an elephant tree. Its trunk is soft and pulpy, like a carrot instead of wood, and if you lean against it you find that it is warm from the sun and you expect to hear a great heart beating inside. In the spring, encouraged by moisture, these giants put out huge white flowers resembling gardenias, white as moons and fragrant, that face down toward the earth; during the summer they bear alumlike dry fruits, shaped like pears, which can be eaten. In the Kalahari there is no need of hills. The great baobabs standing in the plains, the wind, and the seasons are enough.

Usually in the hot months only small winds blow, leaving a whisper of dry leaves and a ripple of grass as though a snake has gone by, but occasionally there is a windy day when all the low trees of the veld are in motion, swinging and dipping, and the grass blows forward and back. When there is no wind, heat accumulates in the air and rises in thick, shuddering waves that distort everything you see, the temperature rises to 120 Fahrenheit and more, and the air feels heavy, pressing against you, hard to breathe.

June and July are the months of winter. Then water left standing freezes at night, and with the first light of morning all the trees and grass leaves are brittle with frost. The days warm slowly to perhaps 80 at noon, but by night when the sun sets yellow and far, far away over the flat veld the cold creeps back, freezing the moisture from the dark air so that the black sky blazes with stars. In winter the icy wind, pouring steadily across the continent from the Antarctic, blows all night long.

There are only three months of rain in the whole year, and these begin in December, ending the hottest season when the air is as tight and dry as a drum skin. Under the rainwhich is sometimes torrential, drenching the earth, making rivers down the sides of trees, sometimes an easy land rain that blows into the long grass like a mistthe heat and drought melt away and the grass turns green at the roots. Soon the trees flower, and in the low places the dry dust becomes sucking mud. Towering clouds, miles away, widen the horizon, and all the bushes which stretch in an unchanging expanse over dune after dune now blossom and bear white or red or violet flowers. But the season is short, and the plants bud, flower, and fruit very quickly; in March the drought creeps in, just as the veld fruits ripen and scatter their seeds.

When the rains stop, the open water is the first to dry, making slippery mud and then caked white earth. By June only little soaks of waterholes remain, hidden deep in the earth, covered with long grass. These, which are miles apart, dry up by August, and then travel in the veld is nearly impossible. Because of this, large areas of the Kalahari remain unexplored.

We have crossed this desert three times, my family and I, on three expeditions, which usually numbered between ten and fourteen people and included my father, my mother, my brother, and myself, as well as other Europeans who were linguists, zoologists, botanists, or archaeologists, sent by universities of the Union of South Africa, England, or the United States, as well as four or five Bantu menseveral interpreters, a cook, and a mechanicwho were the staff. We usually traveled in four big trucks and a jeep, and had to carry all our food and water, gasoline, and equipment in supplies to last us for several months. We crossed great drought areas, once crossing four hundred miles of the central desert of Bechuanaland where there was no water at all, and once traveling every day for two weeks into an unmapped part of the desert of South-West Africa, close to the Bechuanaland border, where we found a waterhole and refilled our empty drums. All this was for the purpose of filming and studying the life and customs of the people of the Kalahari, who are called the Bushmen.