Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

AFFLUENCE WITHOUT ABUNDANCE

CONTENTS

This book is the result of nearly a quarter of a century working among southern Africas San peoples. It is the product of many close friendships forged over this period as well as many interviews with and incidents involving people I know less well. In some instances, I have changed peoples names or disguised them in other ways to protect their privacy.

There are many other people whose thoughts and lives have shaped this book but whose individual stories are largely absent. None more so than my friend and mentor !A/ae Frederik Langman, who in 1994 eased me gently into the then unfamiliar and sometimes terrifying reality of the Omaheke Ju/hoansi. !A/ae is now the government-recognized chief of the Omaheke Ju/hoansi. I am proud to say that we still consider each other family. This book is dedicated to him and my many friends at Skoonheid Resettlement Camp in Namibias Omaheke Region.

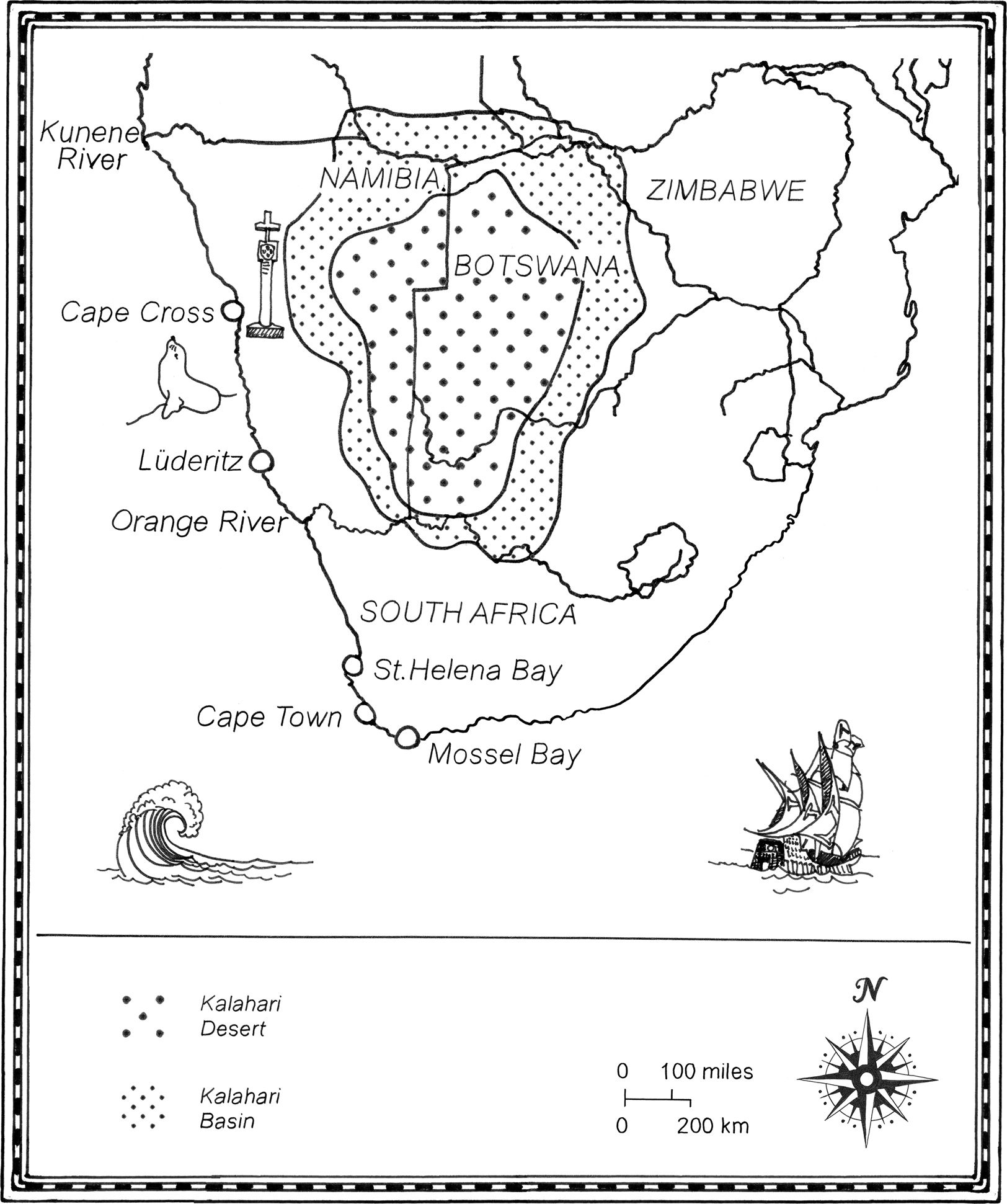

NAMES

In spring of 1904 the German zoologist, linguist, anatomist, and philosopher Leonard Schultze was having the adventure of a lifetime. He had spent several months traveling to German South-West Africa (now Namibia). In addition to evaluating the fishing potential of Namibian coasted waters on behalf of the German colonial office, he hoped to collect a range of zoological specimens to take back to Germany. But his plans were upset by the outbreak of war that year as the German colonial authorities sought at first to subdue and then exterminate the two most powerful peoples in central Namibia, the Nama and the Herero. The Nama were descendants of indigenous cattle- and sheep-herding populations in the Cape of Good Hope on Africas southern tip. By 1904, they had adopted Western dress, weapons, and religion. The Herero were a pastoralist people who had dominated much of central Namibia from the eighteenth century onward. Determined not to let what became the most brutal colonial genocide of the twentieth century ruin his trip, Schultze reported cheerfully that instead of collecting zoological specimens while battle raged he would instead make use of the victims of the war to take parts from fresh native corpses for the study of the living body.

Schultze noted two distinct races of people in southern Africa. He differentiated the smaller-statured, lighter-skinned, click-language-speaking people like Nama and Bushmen from taller, darker-skinned, central-African-language-speaking people like Herero. For the former, Schultze coined the term Khoisan, which has now been widely adopted to describe the indigenous people who lived in southern Africa long before the arrival of both white colonials and other African farming peoples.

The term Khoisan is a compound of the words Khoi (meaning person) and San (meaning hunter-gatherer or vagabond) in the largest of the modern Khoisan language groups referred to by linguists as Khoi. The Khoi (sometimes also spelled Khoe) refers to the small number of Khoisan, mainly concentrated in what is now South Africas Northern Cape Province, who had adopted herding by the time of European colonialism. San refers to Bushmen: people who still made a living from hunting and gathering.

Khoisan have been referred to by many different labels in the past, most of them derogatory. The most widely used have been Bushmanreferring to Khoisan who hunted and gatheredand Hottentotreferring to those who made a living from livestock herding. Both of these terms were coined by others and both carry a burden. The Dutch term boschjesman , from which Bushman originated, was the same word used to describe orangutans in the Dutch East India Companys possessions in Malaysia. The term Hottentot is a crude onomatopoeia intended to invoke the clicking that makes Khoisan languages so distinctive.

Now, as in the past, Khoisan peoples speak many different languages. And each surviving language community has its own name for itself. Names like Ju/hoansi, G/wikhoe, and Hai//om. The term Khoisan resonates little with them.

Beyond a few San individuals who have cut their political teeth in various UN forums or under the tutelage of indigenous rights organizations, I have met few who care a great deal about what terms others use to refer to them. As far as they are concerned, the problem is not how others refer to them but rather how others treat them.

And, as with hunting and gathering populations the world over, Bushmen have encountered monumental prejudice from pretty much every other people they have encountered. The term for Bushmen in the Tswana language, Basarwa, invokes a broad set of crude racial stereotypes and is considered by most Bushmen there to be pejorative. In rural Namibia, most refer to themselves as Bushmen or by the Afrikaans term Boesman. They see little stigma attached to it and some view it as positive, because it implicitly reaffirms their status as a first people with a special connection to their environments. Internationally, the term Bushman is seen as broadly positive, invoking as it does a set of positive if romantic stereotypes. It is for this reason that international NGOs still use the label Bushmen and that it remains the most widely used term for them in international literature. It is for this reason that I use the term Bushmen here.

It is worth noting, though, that some Khoisan political and community organizations have taken the view that San is the most appropriate term to refer to them collectively. As a result, San is gradually supplanting Bushmen in everyday and official use in much of southern Africa and is generally accepted as the most appropriate term by means of which to refer to speakers of Khoisan languages who are descended from populations that hunted and gathered until very recently.

CLICKS

Khoisan languages are distinguished by many things, from their distinctive use of tone to their phonemic complexity. But they are best known for their frequent and expressive use of clicks. The four basic clicks in Khoisan languages are represented by the symbols , !, //, and /. The Ju/hoansi, who are the primary subject of the book, have adopted these symbols into the conventional alphabet to represent major click consonants. For most readers it is simplest to ignore them or substitute them with a hard consonant as many people in Namibia and Botswana who arent comfortable clicking do. Many Namibians refer to the Hai//om Bushmen as Haikom and the Ju/hoansi as Jukwasi.

/ Dental click. This click is made by bringing the tongue softly down from behind the front teeth while sucking in as a mother might in scolding a child with tsk, tsk, tsk.

Alveolar-palatal click. This plosive click is made by bringing the tip of the tongue sharply down the alveolar ridge to the front of the mouth.

! Palatal click. This robust click is made by pushing the tongue into the upper palate and bringing it sharply forward and down to make a popping sound like a cork being pulled from a wine bottle.

// Lateral click. This click is produced by putting the tongue on the hard palate and drawing breath inward over it. It is a sound familiar to many horsemen when egging their horses on.

To hear how the clicks and names are pronounced, please see the website for the book: www.fromthebush.com.