Published in South Africa by:

Wits University Press

1 Jan Smuts Avenue

Johannesburg 2001

www.witspress.co.za

Copyright Jill Weintroub 2015

Images Individual copyright holders 2015

First published 2015

978-1-86814-879-0 (print)

978-1-86814-882-0 (PDF)

978-1-86814-880-6 (EPUB North America, South America, China)

978-1-86814-881-3 (EPUB Rest of the world)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, Act 98 of 1978.

All images remain the property of the copyright holders. The publishers gratefully acknowledge the institutions referenced in the captions. Every effort has been made to locate the original copyright holders of the images reproduced. Please contact Wits University Press at the address above in case of any omissions or errors.

The publishers confirm that this work was subject to an independent, double-blind peer review process before publication.

Edited by Lisa Compton

Proofread by Ester Levinrad

Index by Margie Ramsay

Cover design by Abdul Amien

Book design and layout by Newgen

Printed and bound by Kadimah Print

Preface

T he notebooks and associated papers collected in the 1870s and beyond by Lucy Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek are inscribed in UNESCOs Memory of the World register. Since 1997, the Bleek Collection has been recognised as a documentary heritage of international significance. The landmark 1991 conference in Cape Town, the proceedings of which were published as Voices from the Past: /Xam Bushmen and the Bleek and Lloyd Collection, edited by Janette Deacon and Thomas Dowson, introduced an era of sustained cross-disciplinary interest in this unique collection of material that is most often described as ethnographic. Many academic and popular books, exhibitions and performances have since been created using the Bleek Collection and the interactions between Bleek, Lloyd and their prisoner interlocutors as reference and inspiration.

But my engagement with the collection pre-dated all that. It began in the early 1990s, when, as a reporter for one of Cape Towns daily newspapers, I interviewed Pippa Skotnes about her critically acclaimed art book Sound from the Thinking Strings. In that work, Pippa explored the final years of /Xam life and paid homage to the words of //Kabbo and to bushman cosmology through a series of etchings drawn from rock art motifs. The artworks were presented alongside contributions from Pippas colleagues at the University of Cape Town (UCT), including poetry by Stephen Watson that drew on the /Xam notebooks and essays by archaeologist John Parkington and historian Nigel Penn.

I did not know then that my interest in the collection and the drama of its making would keep me busy for many years. While working on my MPhil at UCT in the early 2000s, I researched the story of Otto Hartung Spohr and discovered how his dedicated detective work and roots in pre-World War II Germany and Eastern Europe had played out in his study of German librarians at the Cape and of German Africana, and in his writings on the life of Wilhelm Bleek.

While employed as a librarian at UCT, Spohr travelled to archives in Germany in the 1960s and crossed the Iron Curtain while on the trail of ma terial pertaining to Wilhelm Bleek. His obsession, described as some sort of madness, added much of the personal detail now taken for granted in the Bleek Collection, including the courtship letters between Wilhelm and his future wife, Jemima. As I read his correspondence, it became clear to me that Spohrs interest in Wilhelm Bleek was as much emotional as it was professional. The empathy he felt towards Wilhelm Bleek, combined with a profound nostalgia for the Eastern Europe he had been forced to flee in the 1930s, leapt out at me as I read his letters.

I began to realise how much Spohrs personal quest and his passion were embedded in a collection of documents that are now often mined for other reasons. This realisation led me to the person of Dorothea Bleek. Why had so little been said or written about her? Why was she the one labelled as racist while Lucy and Wilhelm were celebrated as liberal thinkers ahead of their time? Was there nothing more that could be said about Dorotheas life?

Of the five Bleek daughters, Dorothea alone continued with her father and Lucys bushman work. If it had not been for Dorotheas continued interest in bushman studies, her years of working alongside Lucy and her inheritance of the materials originated in Mowbray that have been a rich resource of creativity and intellectual labour for decades, the Bleek and Lloyd collection as we know it today may never have come into being.

I was intrigued by the silence around Dorothea. So began my journey through her archive, a journey that found me at times frustrated by her seeming lack of openness to new ideas, and at other times impressed by her determination to go into the field and see for herself. I began by reading Dorotheas 32 field notebooks in the Bleek Collection. Apart from two brief diaries recorded on early trips, much of the material in those pages is incomplete, ranging from vocabulary and grammar samples to fragmentary narratives that deal with topics ranging randomly from the weather to the names of stars to children dying of smallpox to snippets of genealogical and historical material, and including many blank or nearly blank pages.

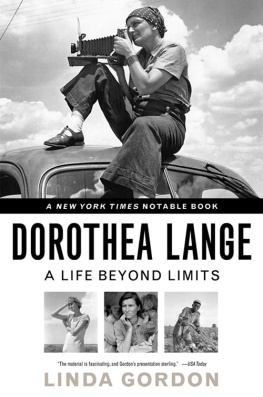

Dorotheas notebooks show that classifying human bodies was a routine part of her bushman work. Delineating human types on the basis of physical attributes, ways of life and language were intrinsic to her research. In addition to measuring such intimate spaces as nostrils, Dorothea dug up human skeletons and participated in making life casts drawn from live human models.

Dorotheas programme of physical measurement, photography and object collection took place alongside language sampling in a context in which such aspects were accepted as a routine part of scientific method that was in turn based on a stable and unchanging conception of race. At the Iziko South African Museum, I looked through the many invasive images she (and other researchers) had taken of people she considered pure examples of bushmen. I wondered about their determination and will to practice science according to the methods of the day that authorised such dehumanising activities.

But my research suggested there was another side to Dorothea. As with Spohr, it was the personal correspondence that allowed a private side of the person to come into view. Through reading her letters to Kthe Woldmann, I realised that Dorotheas scholarship and intellectual quest were driven as much by science as by a nostalgic attachment to the father she had barely known, and a passion and determination to continue the work that he and her beloved Aunt Lucy had begun. It was an expression of her loyalty and respect to their memory. Here, then, was a further example of the feelings, passions and desires that lay at the heart of the archive and of processes of knowledge making, but that were elided in public airings of such knowledge.