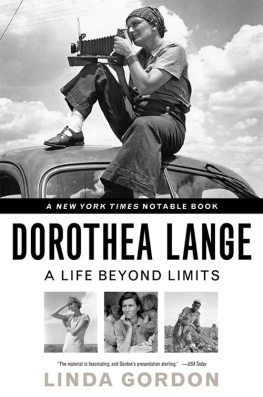

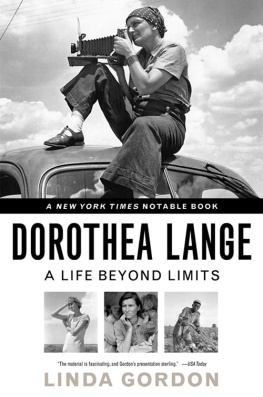

DOROTHEA LANGE

A LIFE BEYOND LIMITS

Linda Gordon

For Allen

CONTENTS

Part I

HOBOKEN AND SAN FRANCISCO

18951931

Part II

DEPRESSION AND RENEWAL

19321935

Part III

CREATING DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY

19351939

Part IV

WARTIME

19391945

Part V

INDEPENDENT PHOTOGRAPHER

19451965

Cossack Rebellions: Social Turmoil in the Sixteenth-Century Ukraine

Womans Body, Womans Right: A Social History of Birth Control in America

(revised 3rd edition published as The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America )

Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence

Pitied but Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the Origins of Welfare

The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction

AS EDITOR

Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored

Images of Japanese American Internment

(with Gary Y. Okihiro)

Americas Working Women: A Documentary History, 1600 to the Present

(with Rosalyn Baxandall)

Women, the State, and Welfare: Historical and Theoretical Essays

Dear Sisters: Dispatches from the Womens Liberation Movement

(with Rosalyn Baxandall)

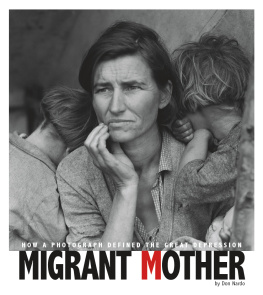

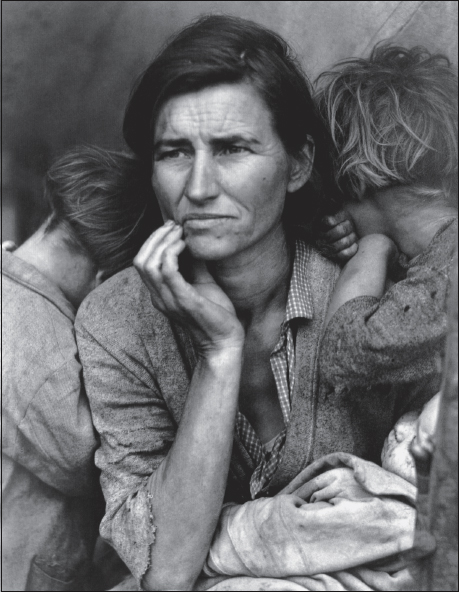

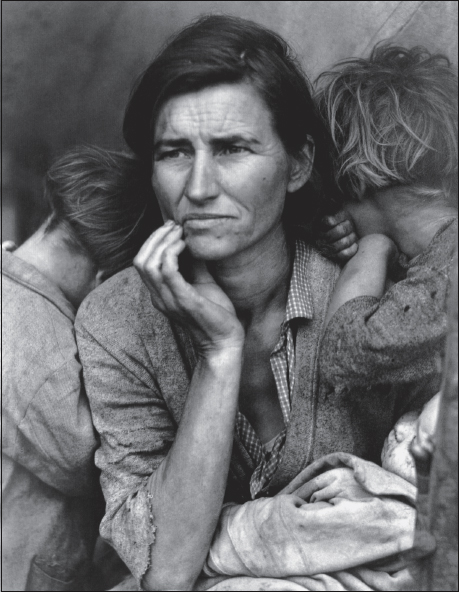

N IPOMO , C ALIFORNIA , 1936

A camera is a tool for learning how to see without a camera.

The visual life is an enormous undertaking, practically unattainable.... I have only touched it with this wonderful democratic instrument, the camera... Dorothea Lange

T his photograph, often called Migrant Mother , is one of the most recognized pictures in the world. It is not the only one of Dorothea Langes to win such famereaders will recognize others in this book. Her photographs often linger in viewers memories as if their intensity etched itself into the mind. Yet many who are familiar with the photographs do not know the name of the photographer and very few know anything about her. This is partly because most of her photographs were published anonymously, and partly because, when she died in 1965 at age seventy, only a handful of photography connoisseurs grasped her genius and her influence. That has changed: in October 2005 a vintage print of one of her photographs sold at auction for $822,400. (See page 102.) She would have enjoyed the money (she earned little from her photography) and the fame (she savored recognition as much as anyone), but she would have questioned what it meant that a photograph of hungry men at a soup kitchen had become a luxury commodity.

I have come to think of Lange as a photographer of democracy, and for democracy. She was not alone in this commitment, for she had predecessors and colleagues, and today has many photographic descendants. From her family of origin, her two extraordinary husbands, and friends of great talent she absorbed sensitivity, taste, and technique. These people are part of her enabling context, and for that reason this book includes them as major characters. So too the unique cultures of Hoboken, New York, San Francisco, and Berkeley play major roles in this story.

The greatest influence on Langes photography, however, was her historical era, so that also demands attention. Her career developed when the severe economic depression of the 1930s created a political opening for expanding and deepening American democracy. President Roosevelts New Deal, responding to powerful grassroots social movements, made substantial progress in protecting the public health and welfare through regulation in the public interest, from securities and credit to wages and hours, and through institutionalizing aid to the needy, such as Social Security. Despite the miseries and fear it engendered, the Depression created a moment of idealism, imagination, and unity in Americans hopes for their country. No photographer of the time, perhaps no artist of the time, did more than Lange to advance this democratic vision. Her photographs enlarged the popular understanding of who Americans were, providing a more democratic visual representation of the nation. Langes America included Mormons, Jews, and evangelicals; farmers, sharecroppers, and migrant farmworkers; workers domestic and industrial, male and female; citizens and immigrants not only black and white but also Mexican, Filipino, Chinese, and Japanese, notably the 120,000 Japanese Americans locked in internment camps during World War II. Late in life her democratic eye reached beyond the United States, as she photographed in Egypt, Japan, Indonesia, and many other parts of the developing world. There too her focus was democratic: she photographed primarily working people through her lens of respect for their labor, skills, and pride.

Most of Langes photography was optimistic, even utopian, not despite but precisely through its frequent depictions of sadness and deprivation. By showing her subjects as worthier than their conditions, she called attention to the incompleteness of American democracy. And by showing her subjects as worthier than their conditions, she simultaneously asserted that greater democracy was possible.

Because her photography was both critical and utopian, its reputation and popularity have varied with dominant political moods. During the Depression of the 1930s her photographs became not only symbolic but almost definitive of a national agenda. The agenda aimed to restore prosperity and prevent further depressions, to alleviate poverty and reduce inequality. It stood for national unity and mutual help, and delivered the message that we must indeed be our brothers keepers. When a more conservative agenda came to dominate in the late 1940s and 1950s, Langes photography became unfashionable, losing currency to more abstract, introspective, and self-referential art. When the civil rights movement inaugurated several decades of progressive activism, Langes photography was again honored and emulated.

As I write at the end of 2008, another major depression makes Langes photography as significant as ever, and for the same reasons. We have today the same need to seenot just look at, but see the struggles of those on the economic bottom. And we also share some of the 1930s optimism, in our case built up through widespread, energetic participation in a presidential election, in which the central issue was whether government would shoulder its responsibility for promoting the health of the society.

It would be a mistake, however, to see Langes photography as politically instrumental. Her greatest social purpose was to encourage visual pleasure. Her messagethat beauty, intelligence, and moral strength are found among people of all circumstanceshas profound political implications, of course. Her greatest commitment, though, was to what she called the visual life. This meant discovering and intensifying beauty and our emotional response to it. Her words about this goal were sometimes corny, but her photographs were not. Although not a religious woman, she was rather spiritual, even slightly mystical in sensibility. Yet she never preached and she abhorred the sentimental.

Because Langes subjects were often from humble surroundings, some have assumed that she herself came from among the disadvantaged. To the contrary, she had educated middle-class parents and operated for sixteen years a very successful, upscale portrait studio in San Francisco, catering to those of wealth and high culture. She was married for fifteen years to Maynard Dixon, a renowned painter. Articles about Lange and Dixon appeared on the society pages of San Francisco newspapers. Her second husband, Paul Schuster Taylor, was an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

Next page