Richard F. Snow

Frederick E. Allen

Timothy C. Forbes

The march of Providence is so slow and our desires so impatient; the work of progress is so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long, that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing ways, and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us to hope.

Robert E. Lee

Letter to Charles Marshall,

ca.1866

We in this countryareby destiny rather than by choicethe watchmen on the walls of world freedom.

President John F. Kennedy

from the speech he did not live

to deliver in Dallas,

November 22, 1963

M Y FIRST THANKS , needless to say, are due to my editor, Tim Duggan; his assistant, John Williams; and my agent, Katinka Matson.

Eleanor Mikucki did an excellent job of copyediting.

I must also express my sincere thanks to the editors and publishers of American Heritage who have given me the opportunity for the last fifteen years to write about the American economy in all its manifold aspects. This book could not have come into being otherwise.

I would also like to thank all those who have helped in many ways, especially: Marc Arkin, Ron Chernow, Walter Olson, Jean Strouse, and William L. Zeckendorf.

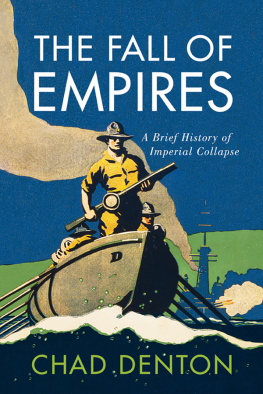

A T THE DAWN OF THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY , the position of the United States in world affairs has no equivalent in history. Indeed, one has to look to the apogee of the Roman Empire, almost two millennia ago, to find even a remotely comparable situation.

Rome conquered the known world by force of arms. Its power arose from its military machine, epitomized by the legions. And every Great Power since has exercised formal political hegemony over alien peoples to advance its own interests. A century ago, the British Empire covered a quarter of the globes land area, while a third of the worlds people were subjects of King Edward VII. But only a small minority of those people spoke English or regarded themselves as British.

The United States, however, has always been, at most, a reluctant imperialist. In the twentieth century it was the only Great Power that did not add to its sovereign territory as a result of war, although it was also the only one to emerge stronger than ever from each of that centurys three Great Power conflicts. Today the United States possesses only 6 percent of the worlds land area and 6 percent of its peoplevirtually all of whom regard themselves as Americans and speak English. And yet its influence in the world is far greater than Britains was at the height of its relative power in the mid-nineteenth century.

The reason is the American economy. For while the United States has only 6 percent of the land and the people, it has close to 30 percent of the worlds gross domestic product, more than three times that of any other country. In virtually every field of economic endeavor, from mining to telecommunications, and by almost every measure, from agricultural production per capita to annual number of books published to number of Nobel Prizes won (more than 42 percent of them), the United States leads the world.

Its economy, however, is not only the largest in the world, it is the most dynamic and innovative as well. Virtually every major development in technology in the twentieth centurywhich was far and away the most important century in the history of technologyoriginated in the United States or was principally industrialized and turned into consumer products here. Its culture, therefore, from blue jeans to Hollywood movies to Coca-Cola to rock and roll to SUVs to computer chat rooms, pervades the rest of the planet. As the new technologies spread around the world, they inescapably brought with them American ways and an American perspective.

English has ever increasingly become the worlds unifying language, as Latin was Europes for centuries. Sixty percent of the students who are studying foreign languages in the world today are studying English, which is increasingly a required subject in school systems everywhere. Partly this is because, thanks to the British Empire, so many countries use English as a first or second language, but equally it is because the United States dominates the world in communications and entertainment. The Internet, the most powerful means of communication ever devised, is largely an American invention, and English is the language of more than 80 percent of the four billion Web sites now in existence.

The ultimate power of the United States, then, lies not in its militarypotent as that military is, to be surebut in its wealth, the wide distribution of that wealth among its population, its capacity to create still more wealth, and its seemingly bottomless imagination in developing new ways to use that wealth productively.

If the world is becoming rapidly Americanized as once it became Romanized, the reason lies not in our weapons, but in the fact that others want what we have and are willing, often eager, to adopt our ways in order to have them too. The relentless spread of democracy and capitalism in recent decades, to a large extent in the light of the American example, is a peaceful and largely welcomed conquestat least by the people, if often not by the elites who have seen their own power slipping away. It is a conquest more subtle, more positive, more pervasive, and, in all likelihood, more permanent than any known before.

Thus Americas is an empire of wealth, an empire of economic success and of the ideas and practices that fostered that success. Like many successes, that of the American economy is often seen, in retrospect, as inevitable, even foreordained. After all, the country has always had a vast, varied, and fecund national territory, abundant natural resources, and a large and well-educated population. But Argentina had all these assets as well, and hasnt fought a protracted war since 1870. Yet it struggles just to maintain its status as a developed nation. Its GDP is less than a third that of the United States per capita.

Much of the reason for the difference lies in politics, for Argentine politics, inherited from Spains control-from-the-top imperial system, has all too often destroyed wealth or, even more often, prevented rather than fostered its creation. But American politics had the great good fortune to be grounded in English traditions, especially the idea that the law, not the state, is supreme. The uniquely English concept of libertythe idea that individuals have inherent rights, including property rights, that may not be arbitrarily abrogatedwas also crucial.

That England was able to develop these concepts, incorporate them into its politics, and pass them on to its children was due in large part to the most consequential geographic fact in Europe, perhaps the world: the twenty-three miles of often treacherous water that separates the island of Great Britain from the European mainland. The English Channel is narrow enough that England was in close and continuous contact with the mainland and yet broad enough to make invasion, at best, a chancy proposition. It has succeeded only once in the last thousand years.