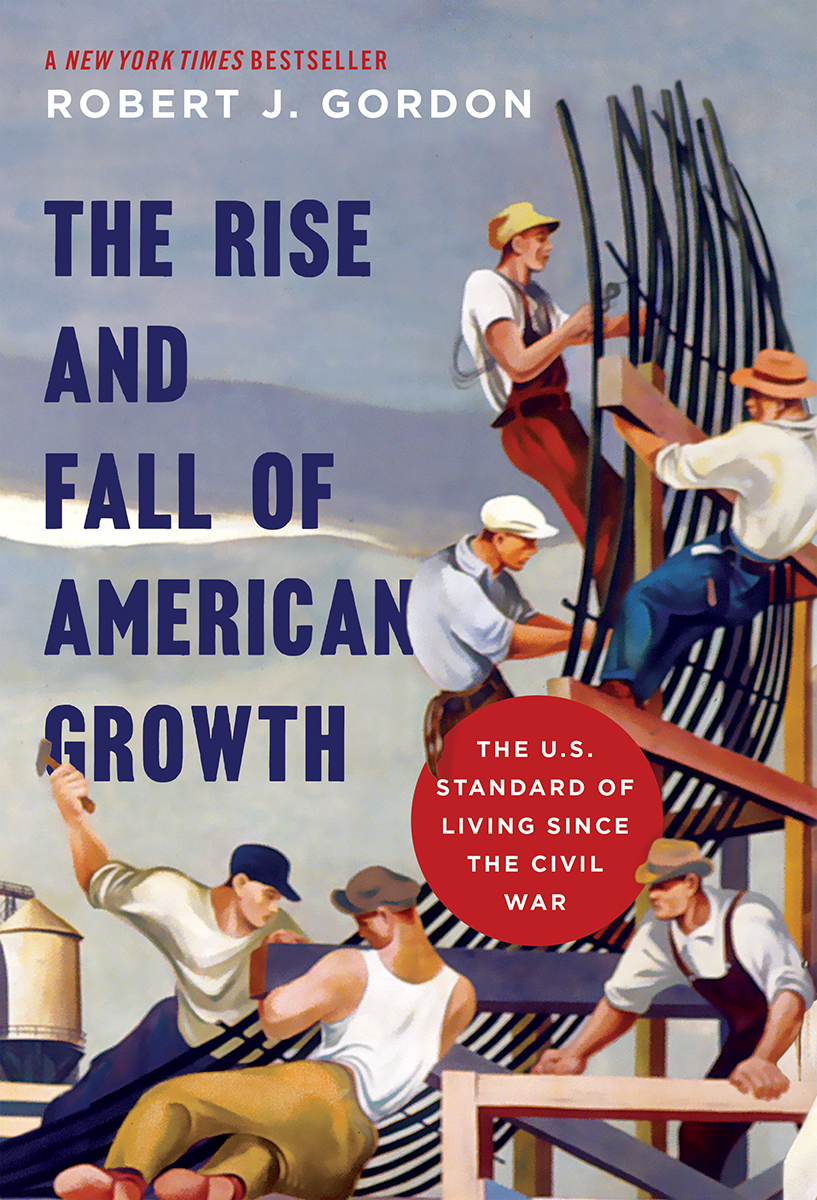

The Princeton Economic History of

the Western World

Joel Mokyr, Series Editor

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book.

For Julie, who knows our love is here to stay

CONTENTS

This is a book about the rise and fall of American economic growth since the Civil War. It has long been recognized that economic growth is not steady or continuous. There was no economic growth over the eight centuries between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages. Historical research has shown that real output per person in Britain between 1300 and 1700 barely doubled in four centuries, in contrast to the experience of Americans in the twentieth century who enjoyed a doubling every 32 years. Research conducted half a century ago concluded that American growth was steady but relatively slow until 1920, when it began to take off. Scholars struggled for decades to identify the factors that caused productivity growth to decline significantly after 1970. What has been missing is a comprehensive and unified explanation of why productivity growth was so fast between 1920 and 1970 and so slow thereafter. This book contributes to resolving one of the most fundamental questions about American economic history.

The central idea that American economic growth has varied systematically over time, rising to a peak in the mid-twentieth century and then falling, in a sense represents a rebellion against the models of steady-state growth that have dominated thinking about the growth process since the mid-1950s. My interest in the mid-century growth peak can be traced back to my 1965 summer job at age 24 after completion of my first year of graduate school in economics at MIT. One of our projects was to research the issue of corporate tax shifting, that is, the question whether business firms escaped the burden of the corporation income tax by passing it along to customers in the form of higher prices. The technique was to compare prices and profits in the 1920s, when the corporate tax rate was low, to the 1950s, when the tax rate was much higher. While the existing literature supported the idea of shifting through higher prices, because before-tax profit rates per unit of capital were substantially higher in the 1950s than in the 1920s, there was no corresponding increase in the ratio of profits to sales. This discrepancy was caused by the sharp jump in the ratio of sales to corporate capital between the 1920s and 1950s.

My summer research on tax shifting led to a term paper that was accepted for publication in the American Economic Review. My PhD dissertation was on the puzzle of the jump in the output-capital ratio between the 1920s and 1950s, which is the counterpart of the rapid rise of productivity growth in the middle of the twentieth century that forms a central topic of this book. While much of the thesis contributed little to a solution, the most important chapter discovered that a substantial part of the capital input that produced output during and after World War II was missing from the data, because all the factories and equipment that were built during the war to produce tanks, airplanes, and weapons by private firms like General Motors or Ford were paid for by the government and were not recorded in the data on private capital input.

In the late 1990s I returned to twentieth century growth history with a paper written for a conference in Groningen, the Netherlands, in honor of Angus Maddison, the famous compiler and creator of growth statistics. Published in 2000, the papers title, Interpreting the One Big Wave in U.S. Long-term Productivity Growth, called attention to the mid-century peak in the U.S. growth process. At the same time there was clear evidence that the long post-1972 slump in U.S. productivity growth was over, at least temporarily, as the annual growth rate of labor productivity soared in the late 1990s. I was skeptical, however, that the inventions of the computer age would turn out to be as important for long-run economic growth as electricity, the internal combustion engine, and the other great inventions of the late nineteenth century.

My skepticism took the form of an article, also published in 2000, titled Does the New Economy Measure Up to the Great Inventions of the Past? That paper pulled together the many dimensions of invention in the late nineteenth century and compared them systematically to the dot.com of this book with its analysis of how the great inventions changed everyday life. The overall theme of the book represents a merger of the two papers, the first on the One Big Wave and the second on the Great Inventions.

The book connects with two different strands of literature. One is the long tradition of economic history of explaining accelerations and decelerations of economic growth. The other is the more recent writing of the techno-optimists, who think that robots and artificial intelligence are currently bringing the American economy to the cusp of a historic acceleration of productivity growth to rates never experienced before. points in a different direction as it finds additional sources of slowing growth in a group of headwindsinequality, education, demography, and fiscalthat are in the process of reducing growth in median real disposable income well below the growth rate of productivity.

Writing began in the summer of 2011. For the chapters in , I knew relatively little and had to start from scratch, aided by a series of undergraduate research assistants (RAs). The first RA was hired soon after the book project was conceived in 2007, and, through the final updating in charts in the summer of 2015, a total of 15 Northwestern undergraduate RAs worked on the project. Their names and those of many others who made this book possible are contained in the separate acknowledgments section at the end of the book.

For the chapters in on 18701940 the sources were primarily library books that formed large stacks on tables in my Northwestern and home offices. The most interesting books were written not by economists but rather by historians and nonacademic authors. My favorite book of economic history is William Cronons Natures Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, which I devoured as soon as it was published in 1991. Two of the most fruitful sources in writing the early chapters were Thomas Schlereths Victorian America: Transformations in Everyday Life, 18761913 and Ann Greenes Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America.

The task of writing the post-1940 chapters of , that the Great Depression and World War II taken together constitute the major explanation of the sharp jump in total factor productivity that occurred between the 1920s and 1950s.

When it came time to write about the improving postwar quality of clothing, houses, household appliances, TV sets, and automobiles, I returned to my previous role as a critic of conventional measures of price indexes. Many of the estimates in were developed first in a 2012 working paper on the end of growth, in its 2014 sequel paper, and in innumerable speeches and debates with the techno-optimists.

The resulting book combines economics and history in a unique blend. The book differs from most on economic history in its close examination of the small details of everyday life and work, both inside and outside of the home. It is not like most histories of the evolution of home life or working conditions, for it interprets the details within the broader context of the analysis of economic growth. More than 120 graphs and tables provide new transformations and arrangements of the data. The analysis contributes a joint interpretation of both the rapid pace of economic growth in the central decades of the twentieth century and of the post-1970 growth slowdown that continues to this day.