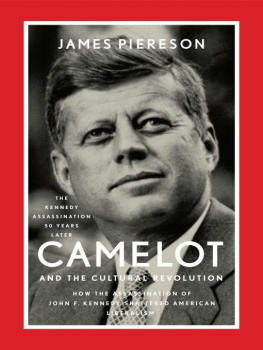

2015 by James Piereson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

First American edition published in 2015 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax exempt corporation. Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Piereson, James.

Shattered consensus: the rise and decline of Americas postwar political order / by James Piereson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59403-672-9 (ebook)

1. United StatesPolitics and government19451989. 2. Political cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. LiberalismUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Consensus (Social sciences)United StatesHistory20th century. 5. Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 19171963. I. Title.

E839.5.P55 2015

973.91dc23

2 0 1 4 0 4 4 6 2 0

Contents

In the excited aftermath of the 2008 election, many pundits saw Barack Obama as a liberal messiah who would inaugurate a new era of liberal reform and cement a Democratic majority for decades to come. He was predicted to become a Franklin Delano Roosevelt or perhaps even an Abraham Lincoln for our time. The pundits were not alone in saying this: Obama himself said much the same thing.

These forecasts sounded grandiose at the time, and today, more than six years into the Obama presidency, they seem more than a little foolish. In contrast to 2008, Obama now looks less like a transformational president than like a typically embattled politician trying to keep his head above water against a mounting wave of opposition. Extravagant hopes have given way to a struggle for survival. Few still believe that Obama will lay the foundations for a new era of liberal governance. Some observers are pointing toward a more surprising outcome: that Obama, far from bringing about a renewal of liberalism, is actually presiding over its disintegration.

Whether or not that turns out to be so, it is clear in retrospect that President Obama and his supporters were kidding themselves in thinking that his election marked the start of a new era in American life. In fact, the reverse is true: Obama came to power near the end of an era, at a time when Americas postwar system was beginning to come apart under the weight of slowing economic growth, mounting debt, the rising costs of entitlement programs, and a widening polarization between the two main political parties. The consensus that sustained that system had been fraying for decades. A new president taking office in the midst of the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression might have tried to repair that consensus by seeking compromises to address the challenges of growth, debt, and entitlements. President Obama instead did something very nearly the opposite. Believing that he was elected to bring about change, he exploited a temporary partisan supermajority to push through an expensive new health-care program while doing little about the long-term problems that have the potential to bring down the nations tottering system of governance. He placed more burdens on the system when the urgent task at hand was to shore up its foundations.

One consequence of Obamas tenure has been to fray the postwar consensus beyond the possibility of repair. There is no longer enough agreement in the American polity to address any of the nations systemic problems before they escalate to the point of crisis. When it comes, the next crisiswhether in the form of a recession, a stock market collapse, a terrorist attack, or some combination of the abovewill force Americans across the board to adjust to a lower standard of living and the various levels of government to renegotiate the promises made to seniors, students, government employees, and the various individuals and groups that rely on public subsidies. Americans will then be compelled to organize a new system of governance on the remnants of the postwar order, one that can generate the kind of growth and dynamism to support the way of life to which they have become accustomed. Failing that, they will watch their country cease to be a high-functioning nation-state and world superpower.

The aim of this book is to make sense of the rise and decline of Americas postwar political order. To a great degree, it is a tale of the rise and decline of the consensus that evolved in the 1940s and 1950s around the role of the federal government in maintaining full employment at home and containing communism and promoting freedom abroad. That consensus seemed so strong and durable during the 1950s that many historians and political analysts thought it was a permanent feature of American life. It came under heavy attack during the 1960s from student protest movements on the left and from the new conservative movement on the right. It held together, barely, during the Reagan and Clinton years in the 1980s and 1990s, but since then it has come apart altogether. This is evident in various arenas of American life, from politics to higher education and even the world of philanthropy. Parts II and III of this book examine the rise of the postwar dispensation and the centrifugal forces that developed against it in the 1960s, including the Kennedy legend that formed a counternarrative to the consensus view of American society.

A major theme of this book is that unsettled transitional periods of the kind we are now living through have happened before in American historyin the 1850s and 1860s, for example, and later in the 1930s and 1940s. In each period, an old order collapsed and a new one emerged out of an unprecedented crisis; and in each case, the resolution of the crisis opened up new possibilities for growth and reform. No particular consensus or set of political arrangements can be regarded as permanent in a dynamic country like the United States.

The political economy of American capitalism has evolved in distinct chapters, not in cycles or in an orderly sequence as Marxists or developmental theorists would have it. Part I elaborates on this theme, especially in Americas Fourth Revolution. The United States has had three such chapters in its history: (1) the Jefferson Jackson era stretching from 1800 to 1860, when slavery and related territorial issues broke the prevailing consensus apart; (2) the capitalist-industrial era running from the end of the Civil War to 1930, when the regime collapsed in the midst of the Great Depression; and (3) the postwar welfare state that took shape in the 1930s and 1940s and extends to the present, but is now in the process of breaking up. Each of these regimes accomplished something important for the United States; each period lasted roughly a lifetime; and each was organized by a dominant political party: the Democrats in the antebellum era, the Republicans in the industrial era, and the Democrats again in the postwar era. The first two regimes fell under vastly different circumstances: the sectional conflict was a crisis of Americas constitutional system, while the Great Depression was a crisis of capitalism.

Next page