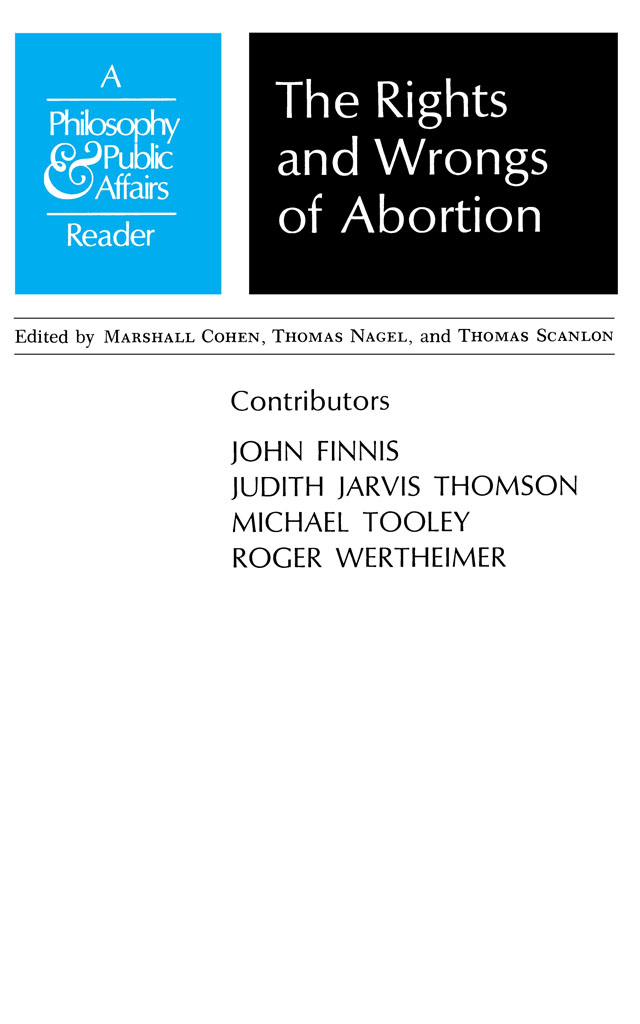

The Rights

and Wrongs

of Abortion

The Rights

and Wrongs

of Abortion

A Philosophy & Public Affairs Reader

Edited by MARSHALL COHEN, THOMAS NAGEL, and THOMAS SCANLON

Contributors

JOHN FINNIS

JUDITH JARVIS THOMSON

MICHAEL TOOLEY

ROGER WERTHEIMER

Princeton University Press

Princeton, New Jersey

Copyright 1974 by

Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey and in the United Kingdom by Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

L.C. Card: 73-8268

ISBN 0-691-01979-7 (paperback edn.)

ISBN 0-691-07197-7 (hardcover edn.)

eISBN: 978-0-69123-316-1 (ebook)

15 14 13 12

The essays in this book originally appeared in the quarterly journal Philosophy & Public Affairs, published by Princeton University Press.

Judith Jarvis Thomson, A Defense of

Abortion, P&PA 1, no. 1 (Fall 1971);

Roger Wertheimer, Understanding the

Abortion Argument, P&PA 1, no. 1 (Fall

1971): copyright 1971 by Princeton

University Press. Michael Tooley,

Abortion and Infanticide, P&PA 2, no. 1

(Fall 1972): copyright 1972 by

Princeton University Press. John Finnis,

The Rights and Wrongs of Abortion,

P&PA 2, no. 2 (Winter 1973); Judith

Jarvis Thomson, Rights and Deaths,

P&PA 2, no. 2 (Winter 1973) : copyright

1973 by Princeton University Press.

Michael Tooley, A Postscript:

copyright 1974 by Princeton University Press.

R0

PREFACE

Philosophy & Public Affairs was founded in the belief that issues of public concern often have an important philosophical dimension and that a philosophical examination of these issues can contribute to their clarification and to their resolution. The editors believe that this expectation is borne out by the following essays, drawn from the first two volumes of Philosophy & Public Affairs. The essays are reprinted here in the order of their appearance in the journal (with a postscript added in one case). They form a consecutive discussion of such fundamental issues as whether a woman has a right to decide what happens in and to her body; whether the fetus is a person; whether it has a right to life; whether there is, in fact, a morally significant difference between abortion and infanticide. These essays are part of an ongoing discussion which can be expected to continue. But they have permanently altered the character of the debate, introducing greater rigor and opening up entirely new questions. They constitute an indispensable source for anyone wishing to think further about the problem of abortion.

M.C., T.N., T.S.

The Rights

and Wrongs

of Abortion

JUDITH JARVIS THOMSON

A Defense of Abortion

Most opposition to abortion relies on the premise that the fetus is a human being, a person, from the moment of conception. The premise is argued for, but, as I think, not well. Take, for example, the most common argument. We are asked to notice that the development of a human being from conception through birth into childhood is continuous; then it is said that to draw a line, to choose a point in this development and say before this point the thing is not a person, after this point it is a person is to make an arbitrary choice, a choice for which in the nature of things no good reason can be given. It is concluded that the fetus is, or anyway that we had better say it is, a person from the moment of conception. But this conclusion does not follow. Similar things might be said about the development of an acorn into an oak tree, and it does not follow that acorns are oak trees, or that we had better say they are. Arguments of this form are sometimes called slippery slope argumentsthe phrase is perhaps self-explanatoryand it is dismaying that opponents of abortion rely on them so heavily and uncritically.

I am inclined to agree, however, that the prospects for drawing a line in the development of the fetus look dim. I am inclined to think also that we shall probably have to agree that the fetus has already become a human person well before birth. Indeed, it comes as a surprise when one first learns how early in its life it begins to acquire human characteristics. By the tenth week, for example, it already has a face, arms and legs, fingers and toes; it has internal organs, and brain activity is detectable. On the other hand, I think that the premise is false, that the fetus is not a person from the moment of conception. A newly fertilized ovum, a newly implanted clump of cells, is no more a person than an acorn is an oak tree. But I shall not discuss any of this. For it seems to me to be of great interest to ask what happens if, for the sake of argument, we allow the premise. How, precisely, are we supposed to get from there to the conclusion that abortion is morally impermissible? Opponents of abortion commonly spend most of their time establishing that the fetus is a person, and hardly any time explaining the step from there to the impermissibility of abortion. Perhaps they think the step too simple and obvious to require much comment. Or perhaps instead they are simply being economical in argument. Many of those who defend abortion rely on the premise that the fetus is not a person, but only a bit of tissue that will become a person at birth; and why pay out more arguments than you have to? Whatever the explanation, I suggest that the step they take is neither easy nor obvious, that it calls for closer examination than it is commonly given, and that when we do give it this closer examination we shall feel inclined to reject it.

I propose, then, that we grant that the fetus is a person from the moment of conception. How does the argument go from here? Something like this, I take it. Every person has a right to life. So the fetus has a right to life. No doubt the mother has a right to decide what shall happen in and to her body; everyone would grant that. But surely a persons right to life is stronger and more stringent than the mothers right to decide what happens in and to her body, and so outweighs it. So the fetus may not be killed; an abortion may not be performed.

It sounds plausible. But now let me ask you to imagine this. You wake up in the morning and find yourself back to back in bed with an unconscious violinist. A famous unconscious violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has canvassed all the available medical records and found that you alone have the right blood type to help. They have therefore kidnapped you, and last night the violinists circulatory system was plugged into yours, so that your kidneys can be used to extract poisons from his blood as well as your own. The director of the hospital now tells you, Look, were sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to youwe would never have permitted it if we had known. But still, they did it, and the violinist now is plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, its only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment, and can safely be unplugged from you. Is it morally incumbent on you to accede to this situation? No doubt it would be very nice of you if you did, a great kindness. But do you have to accede to it? What if it were not nine months, but nine years? Or longer still? What if the director of the hospital says, Tough luck, I agree, but youve now got to stay in bed, with the violinist plugged into you, for the rest of your life. Because remember this. All persons have a right to life, and violinists are persons. Granted you have a right to decide what happens in and to your body, but a persons right to life outweighs your right to decide what happens in and to your body. So you cannot ever be unplugged from him. I imagine you would regard this as outrageous, which suggests that something really is wrong with that plausible-sounding argument I mentioned a moment ago.